Andrew Rosenheim has narrated this article for you to listen to.

When Richard Ovenden of the Bodleian Library wrote to John le Carré asking if the writer would leave it his papers, he got more than he could ever have bargained for. Le Carré not only responded with enthusiasm, explaining that ‘Oxford was Smiley’s spiritual home, as it is mine’, but also sent along 85 boxes of neatly arranged papers and memorabilia. After le Carré’s death in 2020 came a second larger tranche; the total archive consisted of more than 1,200 boxes. This was a writer who threw nothing out.

Selected fruits of this vast haul can be seen in a new and impressive exhibition in the Bodleian’s Weston Library (formerly the New Bodleian).

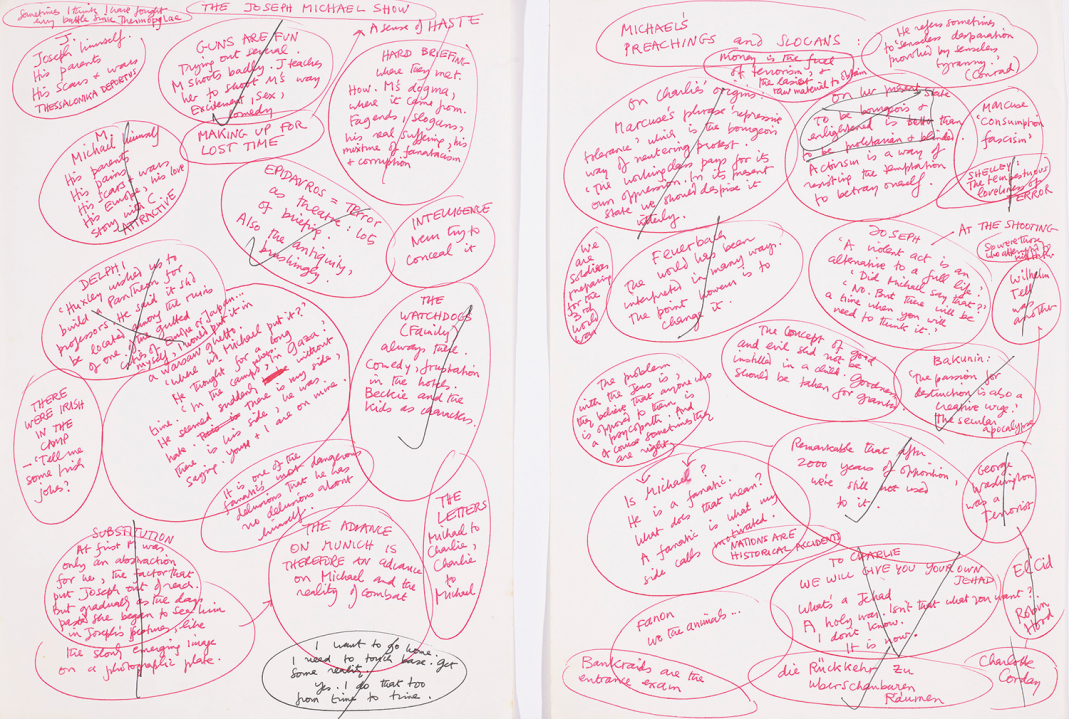

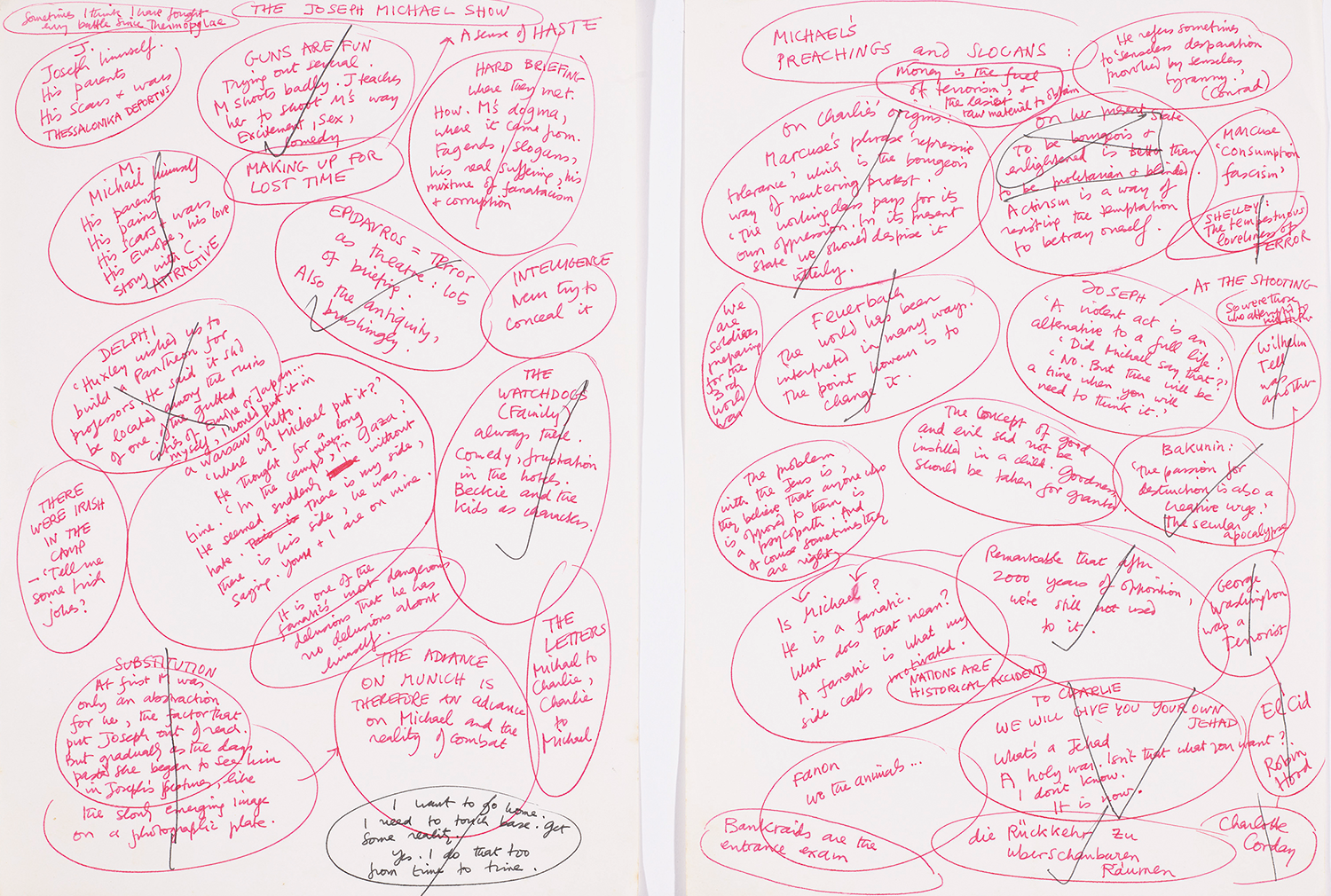

It is organised partly by title and partly by theme, and includes samples of the writer’s annotated typescripts, outlines and notes, flow charts of plots, photos of family members (including his reprobate father), research notes about locations used in his books, original pen and ink sketches and caricatures, and letters both to and from le Carré. It is a remarkable treasure trove, yet constitutes only a very small selection of the holdings now catalogued and available for consultation in the Bodleian.

What the exhibition shows most clearly are le Carré’s working methods. He wrote by hand (except for ‘one-finger email’) and relied on his wife Jane to type the multiple drafts of his novels as well as all his business correspondence (letters to friends were handwritten). Jane was much more than an amanuensis, however, for she had strong publishing credentials as well as secretarial skills, having worked as a publicist and then foreign rights manager for Hodder & Stoughton.

Le Carré tinkered endlessly with the drafts of his books, even rewriting substantially in proof, an indulgence granted by his publishers that other writers can only envy. Tinker Tailor alone went through 30 drafts between 1972 and its publication in 1974 (and for a time had the intriguing title of The Reluctant Autumn of George Smiley). The papers on display do not always tell us much about the finished novels, but they are, at least for le Carré fans, deeply interesting in their own right.

Tinker Tailor alone went through 30 drafts between 1972 and its publication in 1974

There are also insights into le Carré’s insights, as it were, showing the keen authorial intelligence he brought to bear on his creation of character. When Alec Guinness expresses doubts about playing the role of Smiley, worried that he wasn’t round enough or double-chinned, le Carré responds subtly:‘You have a mildness of manner, stretched taut… In the best sense, you are uncomfortable company, as I suspect Smiley is.’ Not all the items on display involve writing: there is the touching inclusion of a suitcase that belonged to le Carré’s mother, virtually the only thing she left behind when she abandoned both her marriage and her two little boys (le Carré was then five years old). It conveys more than any words could our poignant sense of a wound that never healed.

For those who find le Carré’s best work in the Karla trilogy, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1963), and the heavily autobiographical A Perfect Spy (1986), the exhibition will seem lopsided, slanted towards the more recent novels, which required more research as they were often set in exotic locations. For a writer of such marvellous fictions, le Carré became increasingly obsessive about facts. His preoccupation with the accuracy of his scene-setting begins with The Honourable Schoolboy (1977), which required two trips to Hong Kong; it intensified when, in the post-Glasnost era, he set many of his books in faraway places. ‘Countries are characters too,’ le Carré declared, and he proved an intrepid traveller, visiting Asia, Africa and the Middle East in search of stories reflecting post-Cold War themes – including the rapacity of pharmaceutical multinationals and the venality of the international arms trade. ‘A non-political novel,’ he declared, ‘accepts the status quo. I happen to think the status quo spells political disaster.’ Yet ultimately it is the world he invented rather than the real one he reported on that represents his best work.

For a writer of such marvellous fictions, le Carré became increasingly obsessive about facts

The exhibition is accompanied by a book, Tradecraft, edited by Federico Varese, a longstanding associate of the writer and the co-curator of the exhibition. It will be of greatest interest to aficionados, though it includes a helpful timeline of the writer’s life, and a perceptive and fond recollection of his father by his son Nicholas, author of the recent (and excellent) Smiley successor novel, Karla’s Choice (2024). The exhibition itself is a landmark in two respects. It represents a major collection of materials by an indisputably major writer. But equally important, it reverses the near-monopoly of British archives exercised by American institutions (especially the University of Texas at Austin), and makes the collection of le Carré accessible in the country in which it was so carefully created.

Comments