‘Fashions have changed’, said the Japanese writer Ihara Saikaku in 1688. ‘Certain shrewd Kyoto people have started to lavish every manner of magnificence on men’s and women’s clothes. By then, everyone in Japan was wearing a kimono. But it was the new, eye-catching, sumptuous ones wrapped around a flourishing breed of fashionistas that Saikaku was talking about. How to show off your wealth and status in Edo-era Japan? Wear the latest kimono.

This was the starting point for the V&A’s exhibition Kimono: Kyoto to Catwalk, which opened, then hurriedly closed just days before the lockdown. Those of us lucky enough to catch it can tell you it would’ve been the museum’s summer blockbuster. A few tantalising images from the show are still on their website and the catalogue is available. Fawn over them as an antidote to your work-from-home jogging bottoms and hoodie, and hope the exhibition reopens later in the year.

The bolder the better for samurai. Their plush silk kimono – the oldest, and the first we come across in the show – are embroidered with elaborate and theatrical garden scenes, mountains, musical instruments, birds, insects and skulls. One vibrant kimono from around 1800 was dyed bright red with safflower. Another from around 1730 depicts a rural village surrounded by crisp snow and swathes of purple clouds. It was decorated using yūzen: an innovative technique of rice paste lines, filled in with hand-painted dye. The effect is breathtaking.

Delicate patterns soon took over, as the newly-minted middle-class merchants found ways to get one up on the royals. Their styles might look humble and muted, but they were pricey to produce. Hanging in one corner of the exhibition is a feather-light summer kimono made out of grey gauze from 1850. Its only embellishments: open-weave chinks and a couple of pine trees and sand dunes, brushed on in barely-there sweeps.

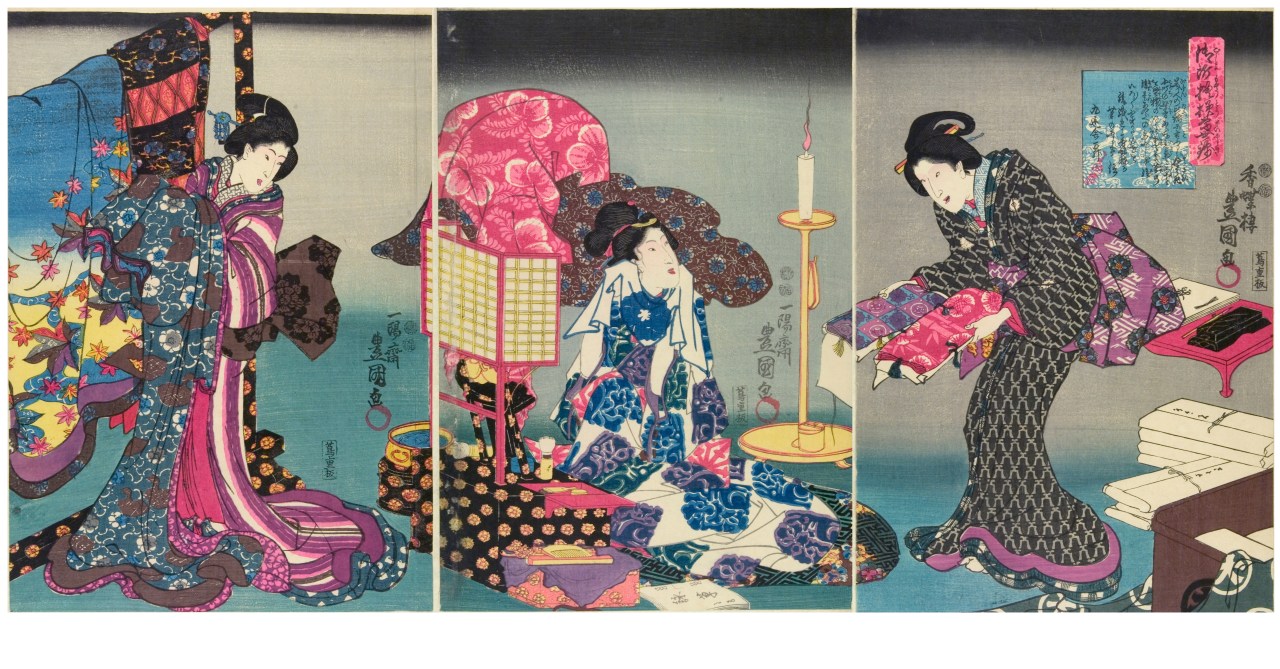

Some trends were set by famous actors and high-ranking courtesans. When the actor Sanogawa Ichimatsu wore a black-and-white chequerboard obi tied around his kimono on stage in 1741, the audience rushed out of the theatre to buy one. In a hand-coloured wood-block print, dated a few years later, we see him glide out of an incense shop, his obi now paired with a chequered kimono. An irresistible pin-up for elegance and agency.

Kimono could be playful and subversive, too. Embroidered on the shoulder blades and sleeves of one from 1750, which is scattered with gold, red, pink and cream maple leaves, are the words from the first line of a ninth-century poem by Bai Juyi: ‘It is cold in the yellow autumn forest’. A popular fabric from around the same time features abstract Japanese characters and swirling symbols. Get a little closer and see the shapes spell the phrase ‘kamawanu’ – ‘I don’t give a damn’.

When Japan opened its borders in the late nineteenth century, most people put on western clothes so that they didn’t appear out of touch. Men wore tailored suits. Women wore their kimono – if they were still wearing them – with fur stoles, gilded clutch bags, elbow-length gloves. Europe and America, though, fell in love with forme Japonaise. Kimono were exotic, almost liberating. Certainly no sign of a corset. We find a striking black-and-white striped coat designed in the 1920s by Emilie Flöge, Gustav Klimt’s life-long companion, all billowing, asymmetrical sleeves and loose draping. Elsewhere, Yves Saint Laurent’s strapless cocktail dress and matching bolero jacket from the 1950s, made of orange silk brocade stamped with gold and silver pine leaves. Its puffball, quilted overskirt reminiscent of the duvet-like kimono worn during fierce Japanese winters. And in his sugary lilac two-piece ‘La-La-San’ (2007) for Christian Dior, John Galliano triumphantly updates the iconic New Look silhouette with details from eighteenth-century kimono: a delicate ribbon obi at the cinched waist, opalescent embroidery and beading, wide sleeves with origami cuffs.

Then comes the costumes. If there was ever any doubt about how versatile this garment can be, look no further. The final room bursts at the seams with Obi-Wan Kenobi’s camel-coloured kimono from Star Wars, and Madonna’s scarlet outfit by Jean Paul Gaultier for her music video ‘Nothing Really Matters’: a mini-dress silk kimono with matching shorts, platform boots and a PVC obi. Fantasize about shimmying around your living room in David Bowie’s white satin tour costume from the 1970s, adorned with creeping black-ink vines and calligraphy. Or Björk’s futuristic warrior get-up, designed by Alexander McQueen, for the cover of Homogenic (1997). Flashes of fiery red lining, scatterings of blue and white blossom, bronze Masai choker.

A couple of clichéd curatorial choices – clusters of bamboo canes; a soundtrack of wind chimes and trickling water – occasionally distracts us from what’s going on. And every piece here, exquisite, enchanting, often surprising, deserves our attention. As the merchants put it 200 years ago with the word ‘iki’: subtlety is more stylish than showiness.

Comments