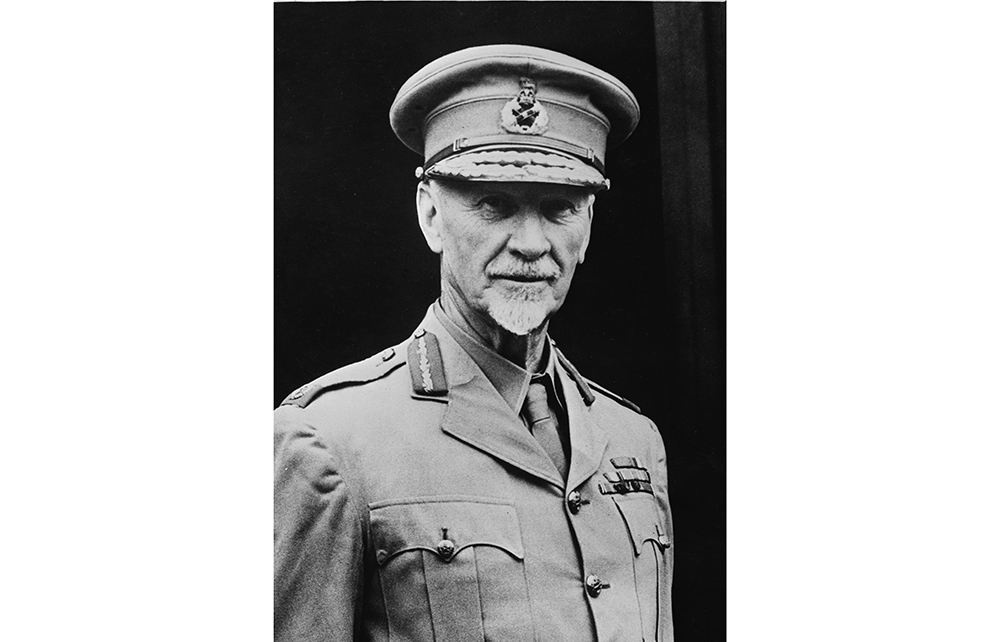

‘Let me tell you about Jan Smuts,’ my grandfather, a doctor born not far from Johannesburg, would begin. And we, as children, would mutter and glance sideways and sink into our chairs. The story would go something like this: ‘Smuts was a Boer War leader, later feted by the English political establishment and central to international moves towards a liberal world order, a segregationist back home and reviled by the Afrikaner nationalists, who instituted formal apartheid from 1948. He was many things to many people, and his influence in South Africa and internationally was unparalleled in his time.’ My grandfather’s eyes would mist over and we would grunt responses about problematic legacies and racism.

Enter Cato Pedder, who, as Smuts’s great-granddaughter, heard even more about the man than I did. Though born in California and raised in England, she feels deep ties to South Africa. Her whiteness and Englishness make her doubly foreign there – uncomfortable in a world of burglar bars, barking dogs and shacks tucked into the lee of mansion walls – and at odds with her family’s hand in bringing the nation about. ‘Identity is fluid and contingent,’ she writes. But how to deal with this inheritance of being a Smuts? Come to think of it, how did being a member of the Smuts family come to mean so much in the first place?

Through the lives of nine women – each one an ancestor – Peddertraces the impact of white Afrikaner identity on 400 years of South African history, from the racially fluid, slave-owning colony in the Cape, through the sclerosis of apartheid and finally to democracy. Her project is to draw these women out of archives that are unconcerned with documenting their lives – archives which say not ‘a word about a woman’s greed for honey, or whether she showed her teeth when she smiled’, and where ‘women’s names are misplaced as they marry’. Fragment by fragment, she brings her forebears to life – from indigenous Krotoa; to Elsje and Angela, both newly arrived, one a slave; to the white Afrikaner women who follow. Each portrait is lively and keenly imagined.

Their worlds are an evolving milieu which Pedder describes and contextualises in detail. She asks how these characters shaped their own tumultuous lives, acting as translators, business women and community stalwarts; and she wonders how they moulded the lives of the children they raised, or what their influence was on the politics of the day. But it is also her own life she wants to understand. Her personal views aside, as a Smuts she is essentially Afrikaner aristocracy, heir to the legacies of white supremacist rule.

Sometimes the writing is almost painfully earnest – for example when Pedder stumbles over how to refer to people and groups, or betrays the breathless self-awareness peculiar to white South Africans. At other times, sentences are hitched one to the next, no conjunctions, no mediation, only proximity – not unlike the churn of experience that brings these women together across centuries and continents.

I was exasperated by the book ending at South Africa’s first democratic elections in 1994. This was a moment of hope that so nearly didn’t happen. When it did, it wasn’t perfect or without cost; and what South Africans of colour put aside for that election has yet to be returned to them. To many South Africans, 1994 is now another inflection point as we unravel the tightly wound constrictions of race, class and gender whose origins Moederland traces. Pedder writes: ‘I realise there is no end to history, particularly not in this joyous, broken nation.’ But concluding on the exultant, just-voted feeling of 1994 leaves a saccharine taste at odds with the questing openness of the rest of the book.

Maybe endings are the least of it, invented and artificial as they can be. Our histories are as easily polished as tarnished. At one point Pedder turns to the American writer Margo Jefferson. How to carry all this history and complicity, all these unruly lives? Jefferson’s advice is: courage and humility. In this deeply personal book, Pedder shows both.

Comments