A major pandemic has been sweeping through the bridge world since the game went online — and it’s called cheating. Who would have thought so many people would succumb to temptation, and what does it say about human nature? ‘Self-kibbitzing’ — that weirdly euphemistic term which means logging on under a different name to see all four hands at your table — has been rife, from club players to world champions (such as the two Janet named in her recent column). Even worse, some pairs have been cheating collusively — yes, actually texting or phoning each other to convey information.

Things are so bad that almost half my bridge friends seem to be employed as cheat-catchers by various bridge bodies. It’s pretty obvious who’s at it: players who regularly make anti-percentage plays or strange bids which work miraculously well, or whose scores have rocketed to implausible heights since lockdown. But the anti-cheat squads still need to sift through hundreds of hands to gather enough evidence to make an accusation or force a confession. So far, only a handful of cheats have been named and banned. More are sure to follow.

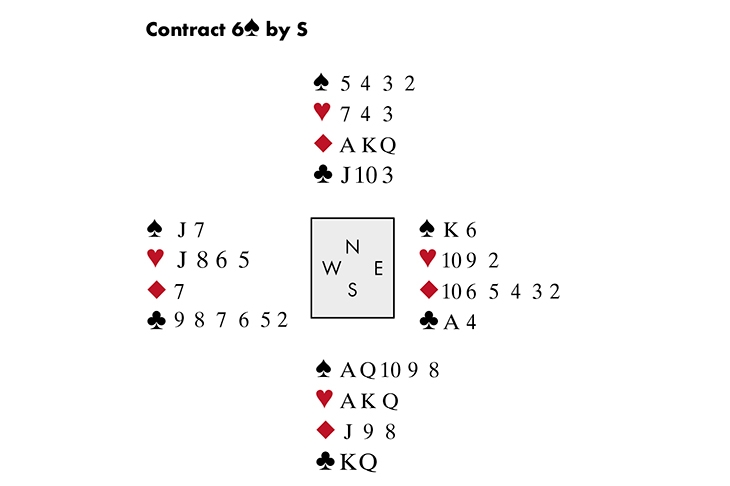

In this climate, it was a relief to play my first face-to-face game since lockdown with friends last week. Defending this hand, Neil Mendoza showed brilliantly how a player can still practise deception without resorting to cheating (see diagram).

Neil led his singleton diamond. I won and played a spade to my ♠Q, whereupon Neil (who knew from the bidding I held five spades) dropped his ♠J! Not suspecting him of being so crafty, I assumed East had begun with ♠K76 and tried to cross to dummy’s ◆K to finesse again. Neil ruffed, and the expression on my face, he told me, was precisely why online bridge could never replace the real thing.

Comments