An oxymoron is a clever gambit in an exhibition title. The Whitechapel Gallery’s Radical Figures: Painting in the New Millennium is designed to trigger the reaction: ‘Radical? Figures?’ before revealing quite how radical the figure can be. But like all good marketing, it is deceptive. Figurative art may have been consigned to history by Clement Greenberg 80 years ago, but history since — neo-romanticism, school of London, neo-expressionism — has repeatedly proved him wrong.

The ten painters in this exhibition aren’t a school: the only thing their work has in common is its statement-making scale. The three-metre canvas at the entrance, Daniel Richter’s ‘Tafari’ (2001), was inspired by a news story about African migrants crossing the Mediterranean to Spain in a small boat; Richter’s over-lifesized orange inflatable dinghy threatens to slide down the wall of black water into the gallery, dumping its bilious boatload of bundled figures at your feet. In the adjacent painting, ‘HEY JOE’ (2011), two men stand heroically silhouetted against a snow-capped mountain: a Taleban fighter is giving the Marlboro Man a light.

The freneticism of Cecily Brown’s ‘Maid’s Day Off’ made me long for the maid to come back and tidy up

Richter is not the only artist here with a sense of humour. Nicole Eisenman’s mural-sized diptych ‘Progress: Real and Imagined’ (2006), painted in the garish palette of a children’s storybook, is packed with surreal, even Pythonesque detail. Amid scenes of hunters in the snow and women giving birth, a giant Terry Gilliam foot has landed, while a puckish little skeleton with folded arms on the bottom left mimics the quizzical embryo in the margin of Munch’s ‘Madonna’. Eisenman sees herself as ‘a developer building 12-storey high-rise condos on the ruins of art history’: her ‘Brooklyn Biergarten II’ (2008) is an update of Renoir’s ‘Dance at the Moulin de la Galette’ with an Ensor death’s head among the crowd.

Tala Madani, who emigrated to Oregon from Iran as a teenager, snaps her fingers at art history: her cartoon figures owe more to James Thurber than to fine art, although the targets of her humour in ‘Sitting in White’ (2008) are Muslim men rather than suburban Mr Monroes. She doesn’t spare her own sex. ‘Shit Mom (Deluxe)’ (2019), with its pink infants crawling around a shit-brown body on a brown sofa, is part of a recent series reflecting her experiences as a mother. It was a relief to me to find only one; when I first saw this series at the Vienna Secession in January there was a whole gallery full.

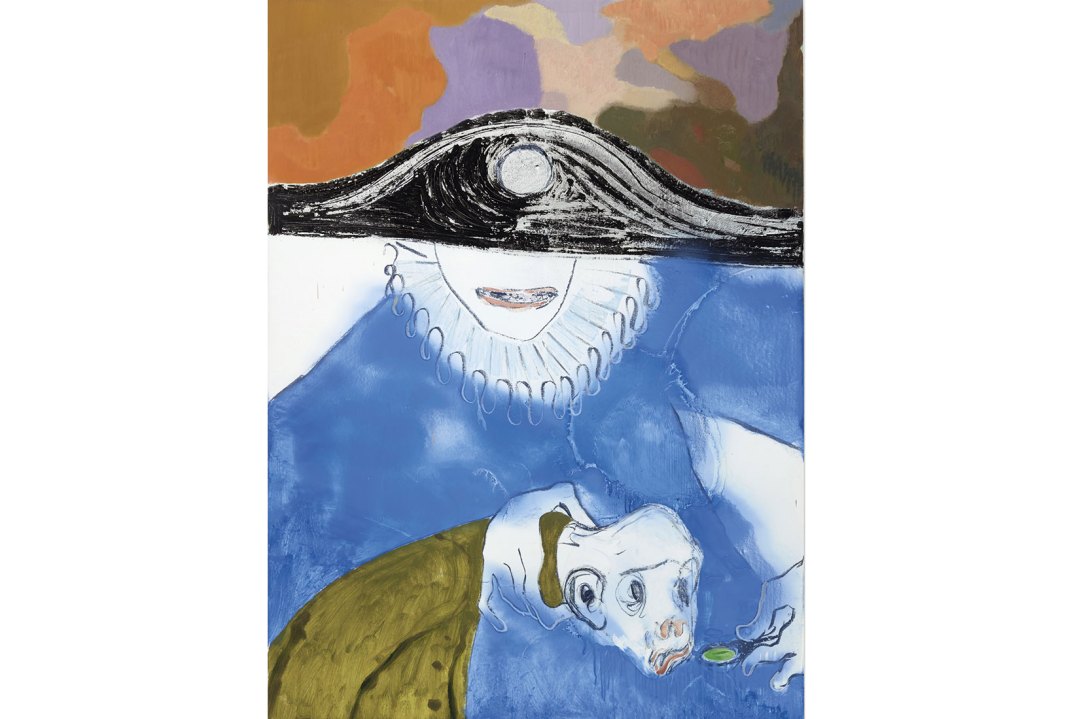

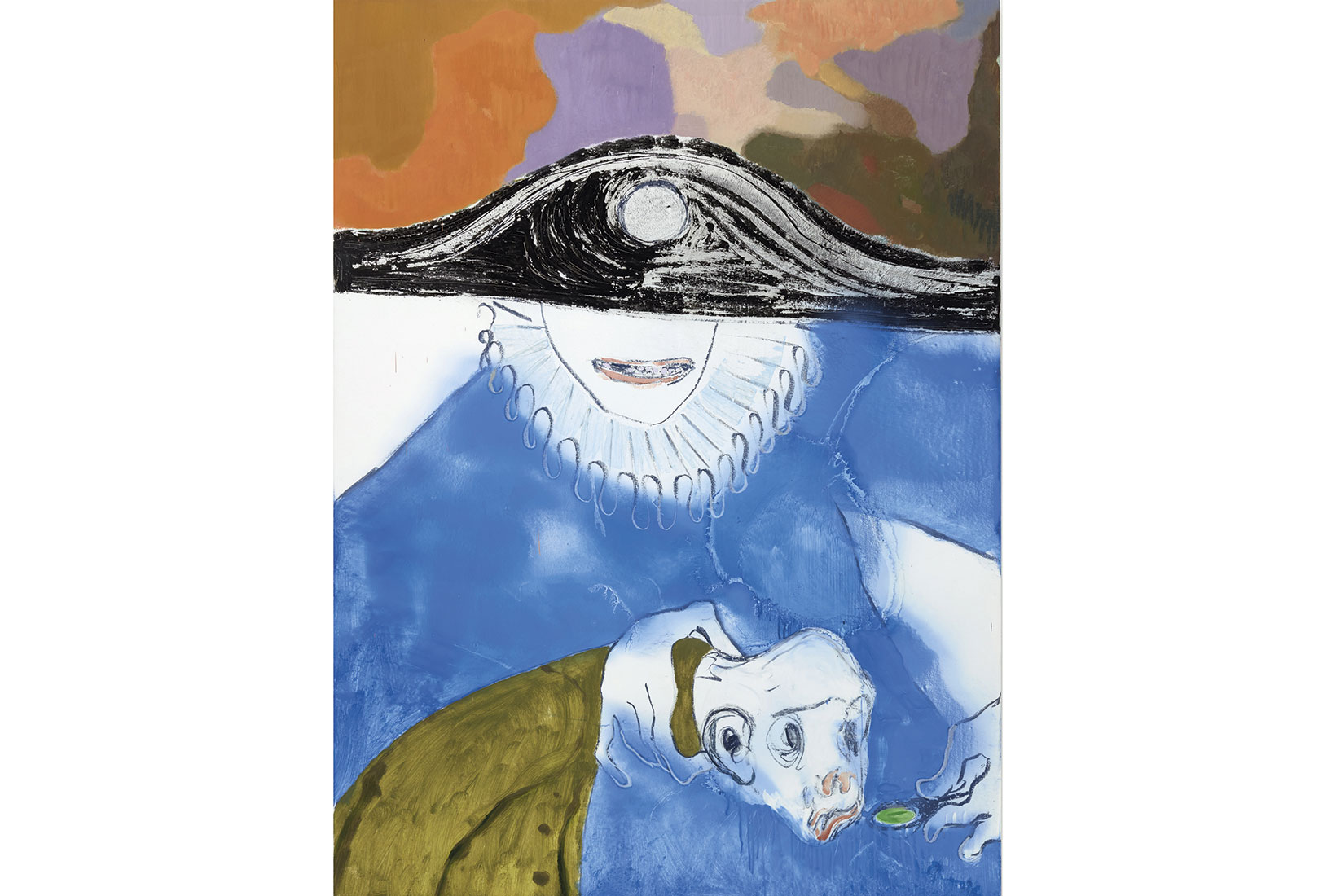

There’s a gentler, more whimsical humour to Ryan Mosley’s paintings, with their nonsense titles like ‘Teaching Snakes to Be Snakes’ (2008); his many-faced ‘Duchess of Oils’ (2014) is a fantastical attempt to imagine an actor playing several roles at once. I missed the simplicity of his compositions in the hyperactive canvases of Dana Schutz and Christina Quarles, two painters who seem to be shouting to make themselves heard above the digital din. And the freneticism of Cecily Brown’s ‘Maid’s Day Off’ (2005) made me long for the maid to come back and tidy up.

There’s a quieter mood to Sanya Kantarovsky’s paintings, though an air of Russian melancholy hangs over them — like many contributors to this exhibition the Moscow-born artist was uprooted to the US at a young age, where he acquired the detached perspective of an outsider. I’ve no idea what’s going on in his painting ‘Letdown’ (2017), but its overburdened mother and slumped child elicited my sympathy; I even warmed to the slithery eel in ‘Friend’ (2018) fixing me with a single glistening eye. Kantarovsky claims to be ‘more interested in our capacity to identify with the pathetic over the sympathetic’. Whatever. He can draw, tugging our heartstrings with the pull of a line.

Nothing exposes weak drawing like the figure. The brown ink studies of Nairobi-born Michael Armitage in White Cube’s current online exhibition Another’s Tongue are strangely lifeless: even his hyenas attacking an old leopard lack movement. This doesn’t matter so much in his paintings on Ugandan bark cloth at the Whitechapel: the seductive handling of thinned paint in ‘Kampala Suburb’ (2014) turns a protest against the Ugandan Anti-Homosexuality Act into a tender image of a same-sex kiss.

Paradoxically, the most animated paintings in this exhibition hardly use paint at all. Tschabalala Self works with appliquéd cloth and draws with stitching, but her jaunty characters are bursting with life. She doesn’t observe humanity with the eye of an alien. She was raised in Harlem, still her home and the subject of her work: in ‘Koco at the Bodega’ (2017), she imagines her sister stopping off at the corner store for a fag and a chinwag. Self has no axe to grind or statement to make; she describes her images as vignettes ‘because each painting captures a moment. I guess the larger narrative is about nothing in particular. In being about nothing, the paintings are about everything’.

Comments