‘It seems to me that I have to choose between 2 extremes of affection for nature… English, or Southern… The latter – olive – vine – flowers… warmth & light, better health – greater novelty – & less expense in life. On the other side are, in England, cold, damp & dullness, – constant hurry & hustle – cessation from all varied topographical interest, extreme expenses…’

That choice was effectively made for Edward Lear in 1837 when he gave up the natural history studies by which he had made his name in his teens and headed south to Rome on doctors’ advice, aged 24. Prone to asthma and epileptic seizures, the myopic artist was now also suffering from eyestrain. ‘My eyes are so sadly worse,’ he wrote to a fellow ornithologist the year before, ‘that no bird under an Ostrich shall I soon be able to do.’

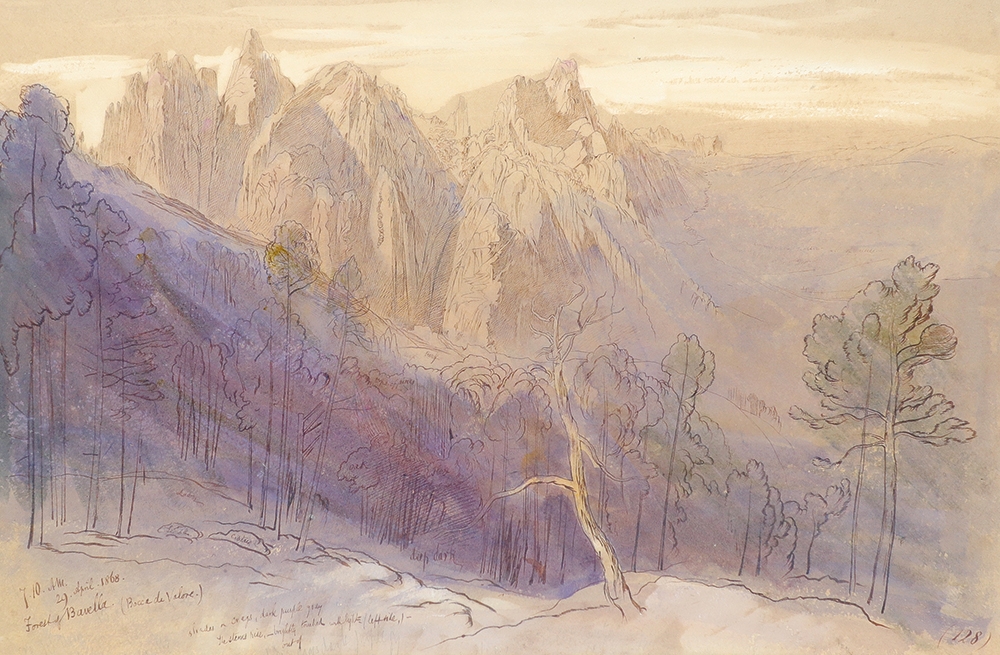

The washes run riot, the melancholy beauty of this pine-clothed mountain pass provoking a fit of sketching

Having plumped for a career as a ‘dirty Landscape painter’, Lear fell into a lifelong pattern of wintering around the Mediterranean and summering in England, dashing from patron to patron, entertaining their families with nonsense songs. His love of birds remained, but the landscape took over. ‘O sugar canes! O camels! O Egypt!’ he hailed the Nile in 1867; ‘O wind! O cold! O stones! O sand!’ he scribbled under a drawing of Savona. His pencilled notes are peppered with exclamations. Lonely, depressive, never quite at home in the circles he moved in, he greeted landscapes as warmly as old friends: ‘The Elements – trees, clouds, &. – and silence… seem to have far more part with me, and I with them, than mankind.’

Not many people think of the author of ‘The Owl and the Pussy-Cat’ as an artist, but it was as an artist that he thought of himself. Self-confessedly ‘half-educated’ – he lasted a year at school, which he hated – he began drawing ‘for bread and cheese’ in his teens, teaching himself from his sisters’ ladies’ drawing manuals. Having caught the travel bug, he became a frantic collector of views – in a 50-year career he amassed 9,000 sketches, some providing reference for later paintings but most merely scratching the itch to capture the moment. When a fellow traveller suggested accompanying him on an outing, he was warned off by Lear’s faithful servant Giorgio, who compared his master to a hunting dog. He would prowl around a subject, catching it from different angles and in different lights, registering the creep of shadows as the sun rose and set. Drawing in pencil to go over later in ink and wash made him very quick.

The 60 sketches in the Ikon Gallery’s new exhibition, the first to focus on Lear’s landscapes, include four views of the Egyptian temple of Maharraka, five of Amada and four of Dendera, timed at intervals as short as five minutes. Three views of ‘Mount Ida, Crete’ (1864) were captured from a passing steamer. There’s no trace of a wobble; Lear had a rock-steady hand and an idiot savant’s ability to transcribe topographical detail on to a page. He took pride in placing things ‘as they really are and not calling to my aid, broken pillars, upset capitals, immense gourds, & 15 Ladies in pink and yellow satin playing on Guitars’. His landscapes are mostly echoingly empty of figures, though a strange penguin-like creature seems to have strayed from one of his nonsense illustrations into ‘Opposite Calvi’ (1868) – ‘a dantesque female’, says a pencil note. He did occasionally indulge in what he called ‘phibbing’.

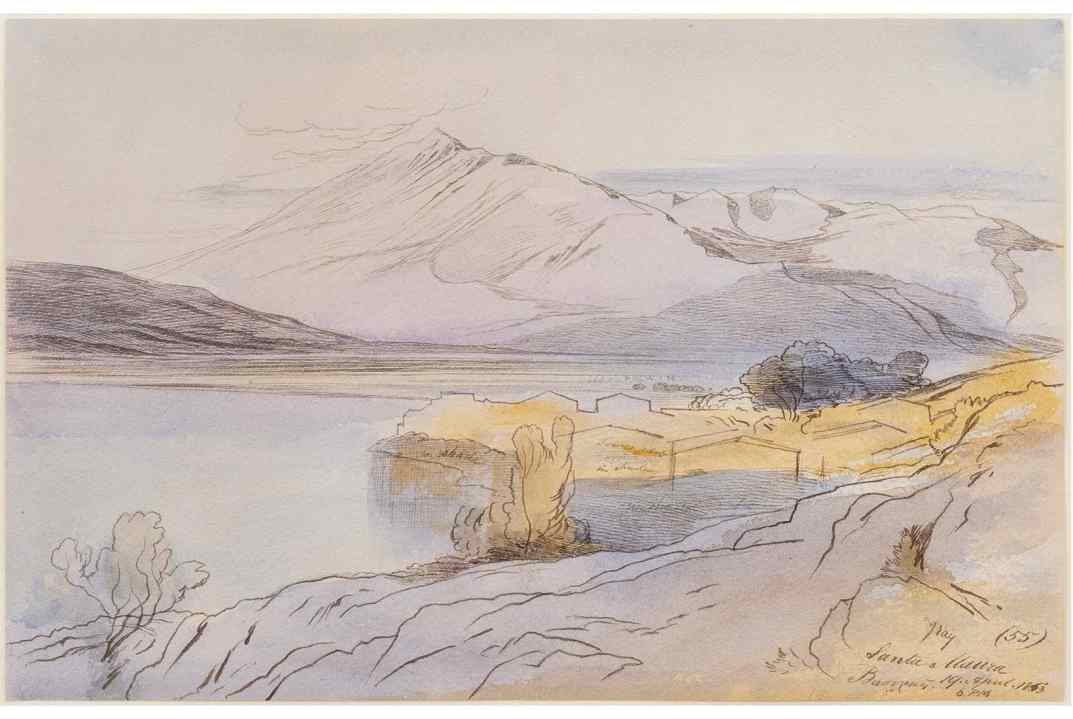

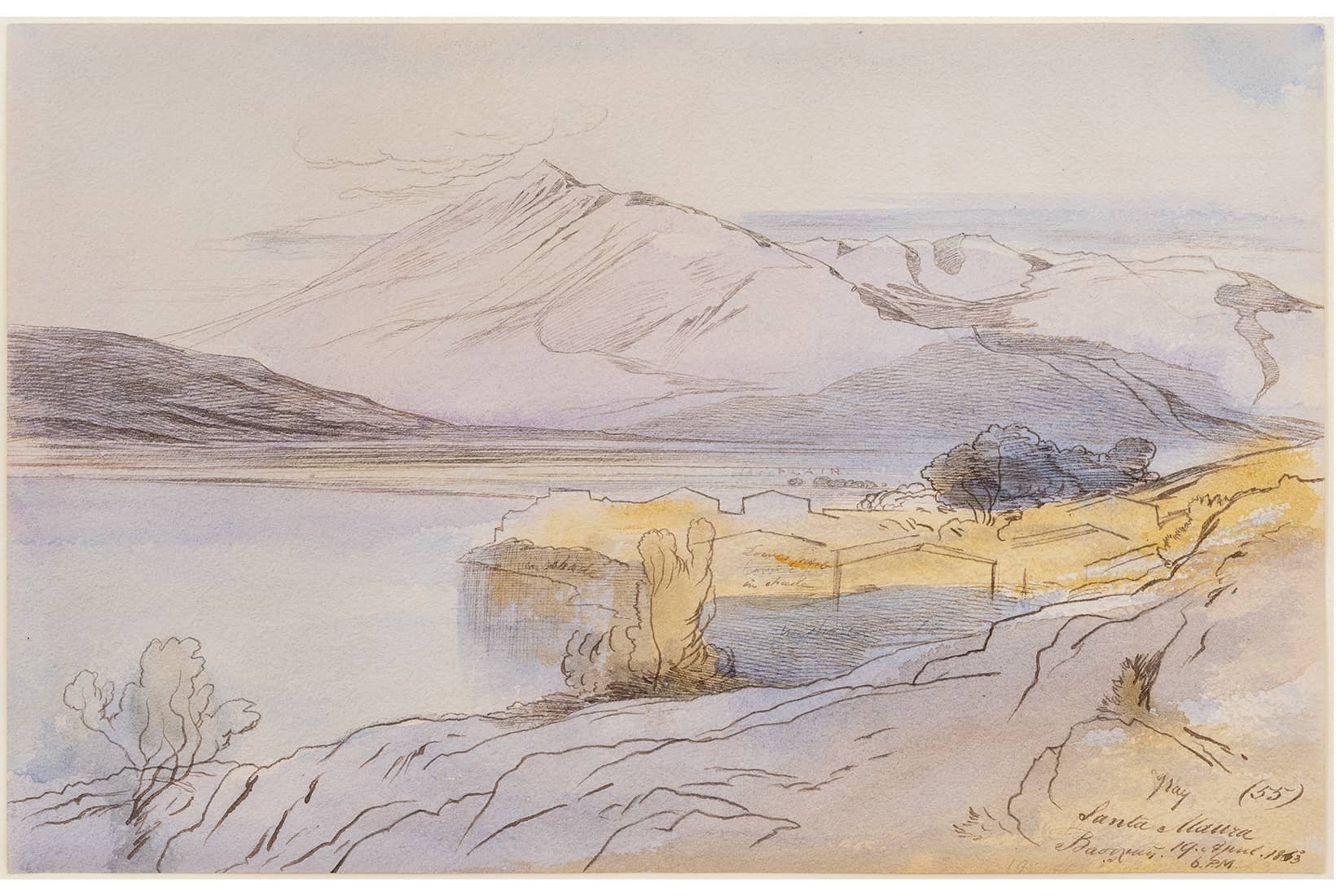

A little sketch of ‘Santa Maura’ (1863) has the freshness of on-the-spot colouring, but Lear’s usual practice was to add washes from notes and memory in the evenings. His chiaroscuro is essentially made up. He is as free with his watercolour washes as he is careful with his line; their refusal to conform to strict tonal logic rescues his landscapes from the realm of plodding topography and spirits them across the border to dreamland. In two iridescent sketches of ‘The Forest of Bavella, Corsica’ (1868) (see below) at sunrise, the washes run riot, the melancholy beauty of this pine-clothed mountain pass provoking a fit of sketching. ‘No frenzy of the wildest dreams of a landscape painter could shape out ideal scenes of more magnificence or wonder,’ he gushed. In two days he produced more than 300 drawings.

Artists are formed by their weaknesses as much as by their strengths. Not having gone through the mill of academic training, Lear never really mastered tonal modelling. His hills have horizon lines but lack contours; they’re flat transcriptions brought to life with light. Unlike the tourist views of David Roberts, Lear’s ‘poetical-topographical’ landscapes have no substance. They don’t promote sightseeing; they prompt reverie. ‘I hardly enjoy any one thing on Earth while it is present,’ he once confessed, hence the urgency of getting it down on paper. He invested everything in capturing the moment, enabling others to enjoy it for him.

Comments