Over the winter of 1859–60, a handsome young man could be seen patrolling the shores of the Gulf of Messina in a rowing boat, skimming the water’s surface with a net. The net’s fine mesh was not designed for fishing, and the young man was not a Sicilian fisherman. He was the 25-year-old German biologist Ernst Haeckel from Potsdam searching for minute plankton known as Radiolaria. In February he wrote excitedly to his fiancée, Anna Sethe, that he had caught 12 new species in a single day — ‘among them the most charming little creatures’ — and hoped to make it a full century before leaving.

Haeckel had a degree in medicine but no interest in treating patients, whose visits he curtailed by holding surgeries from 5 to 6 a.m. A man of prodigious energies who survived on a few hours sleep, he preferred to devote his waking hours to documenting in watercolour drawings the intricate structures of different species of Radiolaria, as seemingly infinite in their variety as three-dimensional snowflakes. With no formal art training, he had an astonishing ability to record complex combinations of spirals, lattices, stars, needles and radial spokes by looking through a microscope with his left eye while focusing on drawing with

his right.

The exquisitely illustrated Monograph on Radiolaria he published in 1862, soon after his marriage, won him the German Academy of Sciences’ highest honour, but on the day of the award — his 30th birthday — his beloved Anna died of a ruptured appendix. From that point on, writes Julia Voss in The Art and Science of Ernst Haeckel, he was ‘consumed by a ferocious universal loathing’ and ‘gradually gave way to the darkest nihilism’. The image is hard to square with a 1904 photograph of a twinkly-eyed Haeckel standing next to a chimpanzee skeleton with a human skull in his hand, looking like a more benign and less simian Darwin. But it helps to explain his development of views on race, euthanasia and war ‘as a continuation of biology by other means’ that today seem inexcusable.

Things would have been fine if this Übermensch of a biologist had stuck to publishing illustrated studies of underwater creatures, from Radiolaria (1862–1888) to Siphonophorae (1869–88), Calcareous Sponges (1872), Arabian Corals (1876), Medusae (1879–81) and Deep-Sea Keratosa (1889). The trouble started when he strayed from marine biology into human biogenetics. Carried away by Darwin’s theory of evolution, he sought to introduce some Teutonic order to the vagaries of natural selection. Darwin scented danger when his young disciple sent him a copy of his General Morphology of Organisms in 1866: ‘My dear Haeckel, Your boldness sometimes makes me tremble,’ he wrote, ‘but… someone must be bold enough to make a beginning in drawing up tables of descent.’ Haeckel’s illustration of the descent of man in the embryology textbook Anthropogenie he published eight years later showed a chimpanzee, gorilla, orang-utan and African up the same tree.

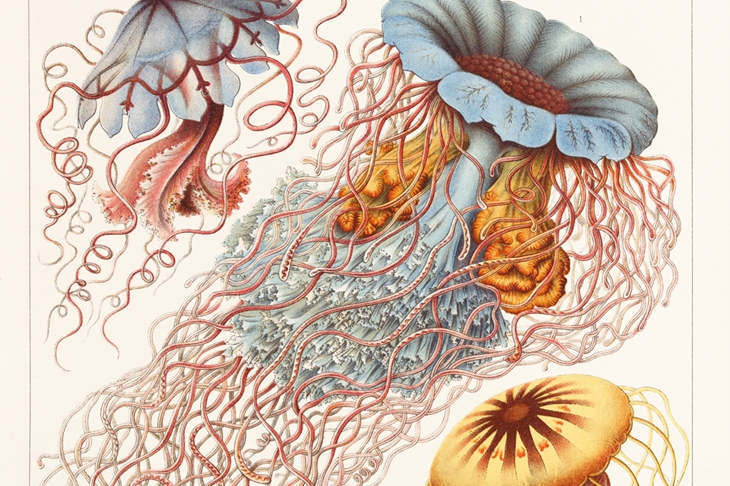

What do you do with a genius with unconscionable views? If he’s an artist, judge him by his art. Fortunately for history’s verdict on Haeckel, his art has lasted better than his science: while his Radiolaria have been renamed Radiozoa and downgraded from multicellular to unicellular organisms, his dazzling draughtsmanship remains undiminished. It takes an illustrator’s skill to describe such minutiae, but an artist’s imagination to bring them to life: if the frills and furbelows of Haeckel’s ‘Desmonema annasethe’ (1879) evoke lacy lingerie blowing in a breeze, it reflects the fact that he named this particular jellyfish in loving memory of his first wife, just as he later immortalised his young lover Frida von Uslar-Gleichen — lost to a morphine overdose in 1903 — in the nomenclature of the jellyfish Rhophilema frida. (His longer-lived second wife of 30 years, Agnes, didn’t have so much as a sea slug named after her.)

It was Frida who assisted him with the preparation of what would become his most influential work, Art Forms in Nature, published in ten instalments between 1899 and 1904. Coinciding with the birth of art nouveau, its treasury of biomorphic wonders was plundered for inspiration by architects and designers. Amsterdam’s new Stock Exchange, opened in 1903, and Monaco’s Oceanographic Museum, launched in 1910, both boasted chandeliers modelled on Rhophilema frida, but the most extraordinary monument to Haeckel’s art was the entrance to the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris designed by René Binet after Clathrocanium reginae, a species of Radiolaria resembling a Prussian spiked helmet.

Haeckel’s influence on the fine arts is harder to measure. The connections Voss makes with Kandinsky and Klimt seem a little forced, but Max Ernst’s snappily titled ‘The Gramineous Bicycle Garnished with Bells the Dappled Fire Damps and the Echinoderms Bending the Spine to Look for Caresses’ (1920–1) is a clear descendant of Haeckel’s calcareous sponges. The 600 pages of stunning plates in this sumptuous book could win him a whole new generation of artist followers, just as long as they stick with the marine invertebrates and avoid the apes.

Comments