The King James Bible, while uniting the English-speaking world, gave birth to centuries of radicalism and Dissent. On its 400th anniversary, Philip Hensher examines the translation’s legacy

Considered as a book, the Bible is far too long. Its characterisation is not all it should be: its hero, God, seems totally inconsistent, varying from a prankster with a bizarre sense of humour (Job) to a sensible dispenser of advice. You can’t help feeling that it is really rather patchy in quality: some of it is wonderfully entertaining, such as the Acts of the Apostles and the two Books of Kings, but some of it doesn’t seem to be interested in entertaining the reader one bit. (Look at the difference between the stonking first line of Kings and the droning way Chronicles kicks off.)

Sometimes, the author seems to forget the details of his own story rather quickly — God creates man twice within about 200 words in Genesis. The poetry can be very good; Ecclesiastes takes the palm (‘And the doors shall be shut in the streets, when the sound of the grinding is low’). Sometimes it’s frankly a bit vulgar, with a sort of anti-talent for metaphor, as in the Song of Solomon: ‘Thy teeth are like a flock of sheep that are even shorn, which came up from the washing.’ The dialogue can be sharp and snappy — ‘Am I my brother’s keeper?’— or the very opposite, as in Satan’s camp response when God asks him, in Job, what he’s been up to: ‘Going to and fro in the earth, and walking up and down in it’ (my absolute favourite line in the entire Bible).

Of course we have only recently begun to consider it in this light — as a book — and its narrative strategies and style are still the concern of very few of its readers. And there are many Bibles, and many still to come; Daniel Everett’s interesting recent book, Don’t Sleep, There Are Snakes, sets out the challenges of translating the New Testament into Piraha, a South American language of unique morphology and concepts.

But for the English-speaking world, the Bible is simply in English, and the English Bible is the King James Bible. Was George Bernard Shaw being serious when he made Professor Higgins say: ‘Your language is the language of Shakespeare and Milton and the Bible’? What he meant was, of course, the King James version. But the translation and the book were for centuries synonymous.

Melvyn Bragg has given us an enthusiastic and wide-ranging account of the effects of this translation, which often exemplifies this benign confusion. He writes about the impact of biblical thinking on writers and philosophers without troubling to show that it stems directly from this particular version. A paragraphs begins: ‘The Great Gatsby has been analysed in Christian terms’, but fails to explain what Scott Fitzgerald drew from the translation.

This general assumption that Christianity and the King James Bible are pretty much the same thing takes Bragg to some strange places. It is odd to quote the beginning of T. S. Eliot’s ‘The Journey of the Magi’ and say merely: ‘Eliot leads us expertly into this story from the Gospels.’ As he ought to know, the first lines are a quotation, not from the Bible, but from a Nativity sermon preached by Lancelot Andrewes, one of the translators.

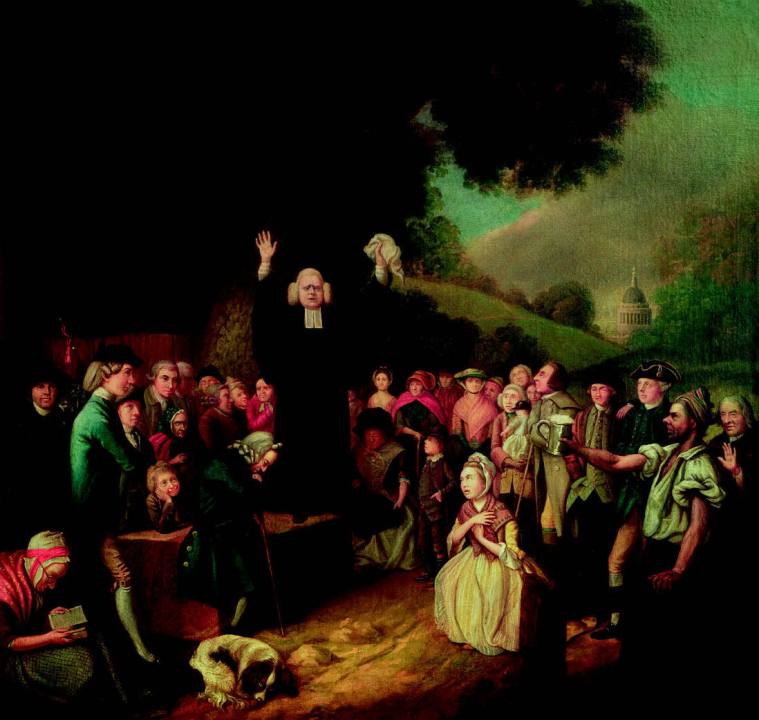

Bragg’s interest is in the ways in which the translation of the Bible into the vernacular, once embarked upon, had all sorts of direct and indirect repercussions. His primary concern is, quite rightly, the history of Dissent and radical thought. Bible translations into English can be shown to have a central place in this tradition, going back to Wycliffe in the 14th century. After Wycliffe’s remains were burnt and thrown into the River Swift as those of a heretic, a Lollard prophecy was made:

The Avon to the Severn runs,

The Severn to the sea.

And Wycliffe’s dust shall spread abroad

Wide as the waters be.

And so it did.

The publication of the Bible in English, from Tyndale onwards, had the effect of spreading literacy and education. Direct engagement with it created habits of thinking which would ultimately destroy its authority, as Bragg points out. Phrases from the Bible were the fons et origo of English radicalism: ‘Every valley shall be exalted and every mountain and hill shall be made low.’ The authority and power of the King James Bible created — as did Luther’s great translation also, in German — a universal template for the language. From the 17th century onwards, the English would be unified across the world by the King James.

It seems extraordinary that it was written in the first instance by a committee. Its creation is explored with great verve by Adam Nicolson in a superb book, When God Spoke English, and in a detailed, scholarly account by David Norton in A Short History from Tyndale to Today. Norton shows how various extravagances were winnowed out of the translation — at one point the ringing phrase ‘flagitious facts’ was preferred to ‘impure ways’ in Peter ii. He has been able to find only one instance when discussion of a particular cadence became contentious — which is unexpected, given that so much of the effect of the version relies on its rhythm.

The result has always been hailed as a pinnacle of English prose. Certainly English prose is full of it. It is hard to write for long before resorting to some phrase from the King James translation, including even ‘to fall flat on one’s face’. The style of the Bible is such a model for elevated utterance, from Donne to Cormac McCarthy, that it is easy to think that its prose has an innate greatness. When any old English novelist wants to write something moving and grand, he or she normally goes for the biblical cadence. It was noticeable, for instance, in the last of the Harry Potter novels that when one of J. K. Rowling’s characters died a sad death, it was signalled by an initial conjunction:

And then with a little shudder the elf became quite still, and his eyes were nothing more than great, glassy orbs sprinkled with light from the stars they could not see.

Where does this habit come from? Why, Genesis, of course:

And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep.

There are two possibilities here. One is that the King James Bible was simply written by the greatest prose writers ever to have worked in English. The other, which I find the more tempting idea, is that the glamour and status of the King James created standards of judgment according to its own nature; it set the rules of a competition that it was always going to win. Objectively, there is some splendid writing in the Bible, but not much, aesthetically, to equal Sir Thomas Browne at his best.

Bragg’s book could have focused more on its ostensible subject, from which it often strays confusingly. It is surprising to find a section on the influence the King James version had on Shakespeare, since it was published after Shakespeare had finished writing his plays; but this is Bragg’s explanation:

Shakespeare quotes hundreds of times from the Geneva translation, and because of the overlap between the Geneva and the King James it is possible to claim that Shakespeare was influenced by most of what would become the King James Bible.

So, not from the King James Bible at all. He also finds space to consider the ludicrous idea that Shakespeare translated Psalm 46 and slipped his name in, in cipher.

About the later influence of the King James translation, Bragg skips over many beguiling minor writers in favour of vague connections with the great. The parodies in the 18th century, beginning with Pope’s Newton epitaph, should have been explored, and the influence of biblical style on Christopher Smart or Walt Whitman is much more interesting than vague echoes in Wordsworth’s ‘Ode on the Intimations of Immortality’. Bragg’s focus on Dissent and the traditions of critical thinking fostered by the King James Bible is very welcome. A little less ‘enthusiasm’, in the 18th-century sense, and a little more detail, would have done his subject justice.

And how is this for a mixed metaphor?

It is not surprising that the pendulum swung. There came a moment to throw off the shackles of scholarship and go to the heart of the matter.

But perhaps that is by way of paying homage to the confusions, as well as the energy, of the great original.

Comments