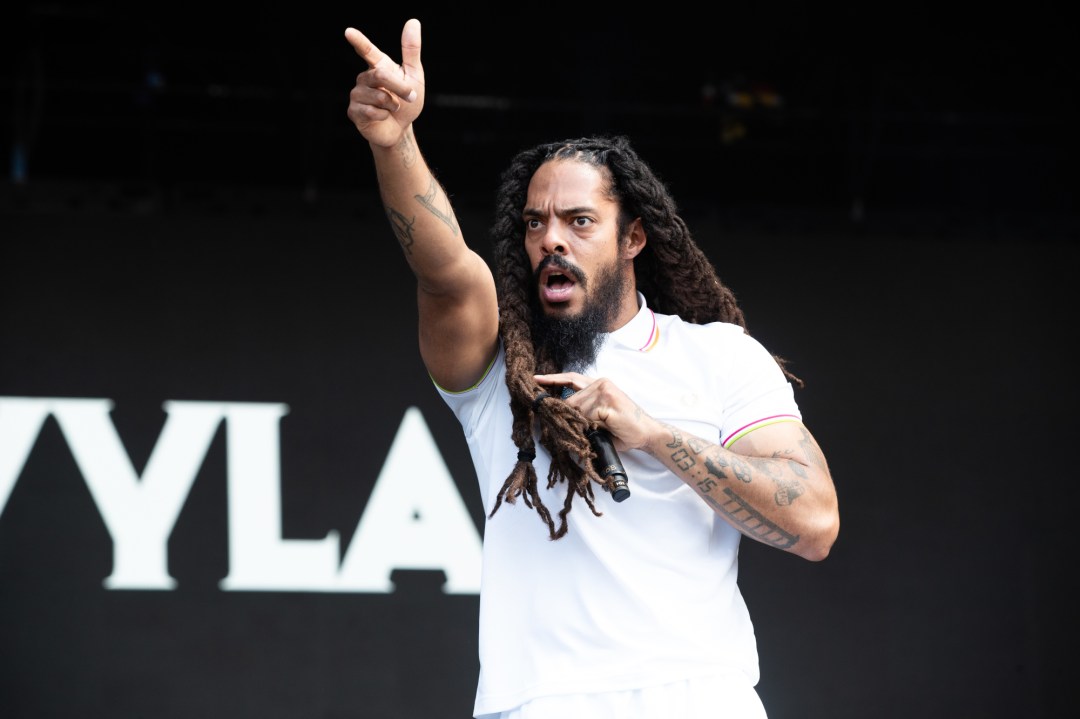

Until last weekend, Bob Vylan were not a household name. I admit that I had never heard of the rap group before. If you’d have asked me, I’d have said he’s a very famous folk-rock star whose name has been misspelt on the publicity material for Glastonbury.

But that really doesn’t matter – because I’m not producing the BBC television coverage of the festival. And whoever was in charge on Saturday should have made it their mission to know everything about all the acts that were going to be featured.

Too many managers shy away from hard decisions, such as calling out poor behaviour and challenging sub-par performance

BBC editors and managers at Glastonbury should have done assiduous homework on Bob Vylan’s previous performances and public statements and assessed the risks of transmitting the act ‘live’. Had they decided that the risks were manageable, they should have had a clear understanding of what lines could not be crossed and what they would do if they were crossed, or about to be crossed.

The events that followed – when the band’s singer led the crowd in chants of ‘death, death to the IDF’ (Israel Defence Forces), and made other deeply anti-Semitic and offensive comments – have once again torn a hole in the BBC’s reputation.

Some have claimed that what happened was another example of the corporation’s bias against Israel and its blinkered approach to anti-Jewish hate. Writing in the Telegraph, Danny Cohen, a former director of BBC Television, says: ‘The BBC has repeatedly shown itself unable to get its own house in order on anti-Semitism, whether that be the racism broadcast live this weekend from Glastonbury, the consistent Jew-hate and bias from reporters on BBC Arabic or the debacle of the Gaza documentary that the corporation was forced to pull because, amongst other things, a payment had been made to the family of a Hamas official.’

Like Cohen, I am Jewish and worked at the BBC for many years (in the News division). However, I don’t share his view of systemic bias. There have certainly been missteps and, on occasion, appalling lapses of judgement (such as the lack of background checks before the Gaza documentary was shown) but the problems owe more to the absence of clear, firm and effective decision-making, supervision and oversight. The management flaws have been heightened over the past 20 months as BBC staff grapple with the complexities of covering the Israel-Gaza conflict – but they are also at the root of most other crises that have faced the BBC, from Martin Bashir’s Diana interview to the Jimmy Savile scandal; from Gary Lineker’s tweets to the crimes of Huw Edwards.

My experience of 31 years at the BBC, first as a trainee, then as a producer and reporter, and finally as a home affairs correspondent covering security, terrorism, crime, policing, justice and immigration was that too many managers shied away from hard decisions, such as calling out poor behaviour and challenging sub-par performance. Difficult conversations were put off and mediocrity was tolerated. Staff were sometimes moved into roles they weren’t equipped for and, inexplicably, people were promoted because they were good in management meetings, despite being lousy at their job.

Of course, I worked with some brilliant BBC editors and chiefs, people who made bold decisions, nurtured talent and took responsibility rather than sitting on the fence. But the kind of blurry thinking and fuzzy decision-making that results in the live streaming of a band spewing race hatred and violence at the UK’s biggest music festival highlights a deep management malaise within the corporation.

Will the BBC address its inadequacies? Its latest statement suggests not. Although the organisation condemned Bob Vylan’s ‘anti-Semitic sentiments’ and expressed ‘regret’ for not pulling the live stream during the gig, it referred to the need to refresh staff guidelines. ‘In light of this weekend, we will look at our guidance around live events so we can be sure teams are clear on when it is acceptable to keep output on air.’

The BBC already has a mountain of official advice – and, just six days ago, it issued a new edition of its key document, the Editorial Guidelines, the first update for six years. The new guidelines don’t come into effect until September – but they could not be clearer about broadcasting ‘extreme’ material. ‘Where output includes views which might incite hatred we must have editorial justification and must include appropriate challenge and/or other context,’ it says. In all, there are 11 warnings about incitement.

There is also a section on ‘live’ broadcasts. ‘We need to assess the risks when producing and broadcasting live output and take any appropriate steps to mitigate them. Considerations include: how live output might be monitored; whether material that has the potential to cause offence is appropriately scheduled; and whether there is sufficient senior editorial support available during transmission. If problems occur in live output, they should be dealt with promptly and sensitively.’

The BBC’s promise to ‘look’ at the guidance again is a smokescreen. Saturday at Glastonbury was a failure to adhere to the (extensive) existing guidance, to apply common-sense and make the right decisions. In other words, the people in charge got it wrong.

I don’t want a witch-hunt, but I do think those who made the mistakes should be held to account for them. Only rarely, in my three decades at the BBC, was appropriate action taken over serious editorial or management failings. That must change. Otherwise the blunders will continue and public support for the corporation, with the licence fee under review, will wither away.

Comments