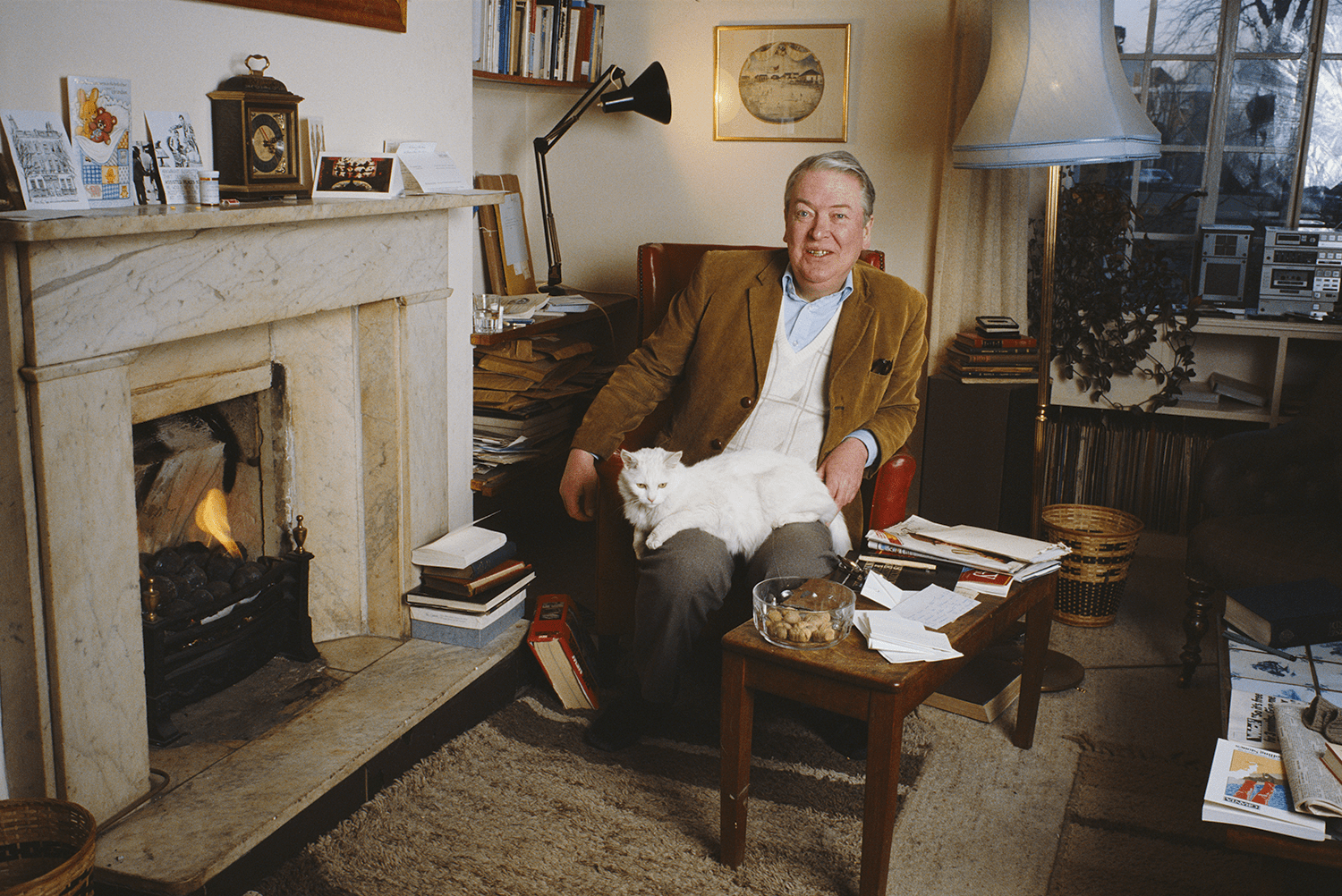

In 1978, I gave a poetry reading at Hull University. Philip Larkin was glumly, politely, in attendance. I was duly appreciative, knowing what it must have cost him. He was deaf as well as disaffected. Perhaps the deafness helped. The next day, we had a lunchtime drink at the University bar. We talked about Kingsley’s recently published Jake’s Thing, a fictionalised account of Kingsley’s sexual relations with Jane Howard. Larkin was puzzled: ‘It’s determinedly foul-mouthed, which I like, but there is a central implausibility. Jake can do it, but he doesn’t want to.’ An innuendo? A suggestion that Jake, and by implication Kingsley, couldn’t? He sipped something improbable like a Dubonnet.

A year previously, Kingsley had taken me to lunch in Wheeler’s. I was teaching at Christ Church and Kingsley wanted to know if I thought an Oxford college might be called St James’s – or ‘Jim’s’ in what he called ‘popular parlance’. I thought it entirely plausible and, as he told me more about the novel, I had several other suggestions of my own. I thought he wanted to pick my brains. He didn’t. I had answered the question he wanted answered. Anything else was an impertinence. He became irritated. Finally, before he had finished his dover sole Walewska, he got to his feet and said he needed a shit. When he returned, he asked me if he had tucked his shirttail in properly. ‘One of my nightmares: everyone knows you’ve just had a shit.’

Sometime later, we had lunch together in La Capannina, an Italian greasy spoon near the New Statesman offices in Holborn. Kingsley, his lips gathered, was in evangelical mode, hot against false gods: ‘Picasso couldn’t draw.’ I smiled warily. It sounded like an accusation. ‘Well, Kingsley, I would agree with you, except that three weeks ago I bought a book called Picasso: Birth of a Genius. And what it shows is that Picasso could draw brilliantly in the conventional way from the age of eight.’ Now, I would add Picasso’s recorded obiter dictum: ‘When I was the age of these children I could draw like Raphael: it took me many years to learn how to draw like these children.’

Kingsley hunched over the table like a chess master, his next move ready. ‘But Schoenberg couldn’t write a tune.’ He leaned back. Checkmate. ‘I don’t want to be difficult,’ I said. ‘But that isn’t true either. Radio 3 has just had an archive week and last Tuesday they played a tape of Schoenberg talking about his Violin Concerto. Which begins sort of like this. [I ‘sang’ the opening.] Schoenberg said some people think it ought to sound more like Tchaikovsky, more like this.’ And Schoenberg rewrote the opening so it sounded like Tchaikovsky. “But you see,” Schoenberg went on, “I think it sounds more interesting like this.”’ And he reverted to his preferred version. ‘And you know, Kingsley, it did sound more interesting.’

Kingsley: ‘Where’s the toilet in this place?’ ‘Immediately behind you,’ I said. (The coincidence has only now struck me that these two anecdotes share a toilet. Perhaps it was Freudian. He was telling me I was a little shit. )

Nowadays, I’d simply cite Schoenberg’s intensely melodic Verklärte Nacht, a piece of music Kingsley certainly knew. Actually, looking back, I think Kingsley was testing me to find out how sycophantic I was. Both his assertions were absurd, as he was quite aware. All the same, his preference was for me to be sycophantic. And I wasn’t.

I think Kingsley was testing me to find out how sycophantic I was

I think his sense of humour was related to the Picasso/Schoenberg assertions. His best jokes were the same: all touched on the transgressive. Larkin’s humour shared the same transgressiveness, the same exaggeration. His letters to Monica Jones are full of unapologetic little Englander provocations: ‘What is Benaud doing in the Press Box? I view him with as much pleasure as I should Göring at Farnborough Air Display.’ You’d forgive anyone anything for being so funny. Larkin again:

Ring a ring a roses

A coronary thrombosis

A seizure! A seizure!

All fall down.

Genius, but not as good as Kingsley’s response to Heathcote Williams, the author of Whale Nation, who was seeking Kingsley’s support to save whales from extinction, of being turned into ice cream, lipstick, margarine, and so forth. Kingsley (mildly): ‘Oh, I thought that was quite a good way of using them up.’ The art of being impossible, of going too far, of finding our pieties ripe for humour.

When I was an editor at Fabers, I asked Kingsley if he would edit the Faber Book of Ageing. In my letter, I quoted E.M. Forster’s unsparing self-assessment (‘anus clotted with hairs’) as a sample. Kingsley was outraged, insulted and on the phone. ‘Am I supposed to find this funny?’ The bakelite burned in my ear. In retrospect, I am puzzled because Kingsley mined so much of his life for literature. Think of One Fat Englishman, a title originally written in lipstick on his sleeping beach body by his then wife Hilly, with the additional rubric ‘I fuck anything’. Eventually, Anthony Burgess accepted with enthusiasm but died before the anthology had made any progress.

Comments