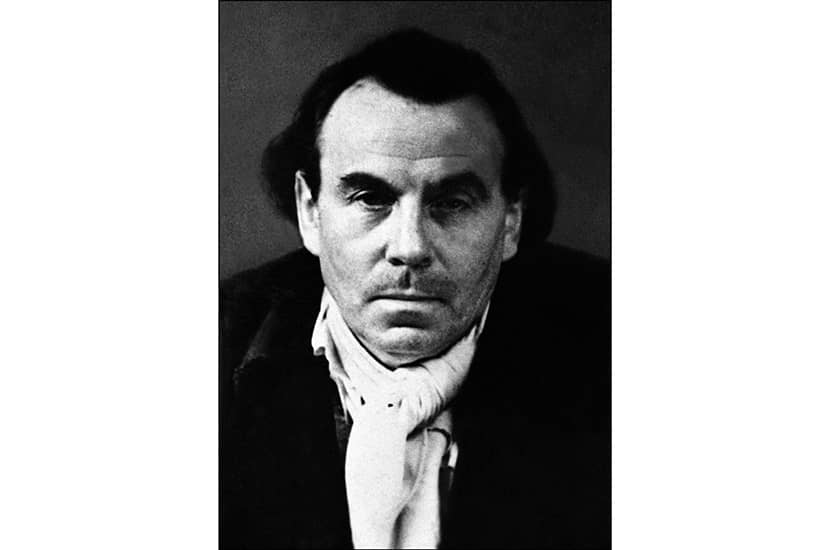

They rather like bad boys, the French. Louis-Ferdinand Céline (1894-1961) is one, in a tradition that stretches from François Villon to the dyspeptic Michel Houellebecq. But provocation doesn’t always get you where you want to be, as the careers of Richard Millet and Marc-Édouard Nabe demonstrate.

Journey to the End of the Night, Céline’s first novel, was a huge success when it was published in 1932 and made him a darling of the left, with applause from Trotsky and Jean-Paul Sartre. That didn’t last long. His virulently anti-Semitic pamphlets (so extreme that André Gide thought he was joking) and his arguments for accommodating Hitler resulted in him going on the run at the end of the second world war.

Damian Catani’s biography of Céline is also an extensive commentary on the work. One of the things you discover when you teach creative writing is that writers rarely invent things: they simply change names to avoid getting sued or beaten up. You read a weird yarn about someone building a ladder to the moon and then find it was the author’s summer job. Catani attaches identities to most of Céline’s characters.

Céline was clearly nutty, like many combatants who survived the battlefields of the first world war

Very much a fan, he makes some effort to lighten the charges against him. I’m not convinced it’s worth the bother; you can either digest the sins or not. Apart from anything else, Céline was clearly nutty, like many combatants who survived the battlefields of the first world war (just look at Robert Graves, or indeed Hitler).

It’s true that Céline never signed up to the Nazi hymn sheet. He wasn’t a member of the Groupe Colloboration (yes, that really was an organisation) like the writers Robert Brasillach or Pierre Drieu la Rochelle, and he was friendly with members of the Resistance. However, as Catani points out, he was probably lucky to be in prison in Denmark after the end of the war; by the time he was tried in absentia, the taste for vengeance had dwindled. Had it not, he might have ended up dead like his publisher Robert Denoël or Brasillach.

In the Anglo-Saxon world (and to a great extent in France too) Céline’s reputation rests on Journey to the End of the Night. The book inflicts such a powerful series of blows on the reader — of the horrors of the war, colonialism and urban poverty — that it’s easy to miss that it’s not really fiction in the conventional sense.

Céline is more a writer than a novelist, as his subsequent work reveals. He is an unobvious, impish inheritor of Théophile Gautier’s l’art pour l’art tradition. His transition to the ‘three points’ (ellipsis) and exclamation mark phase after the second world war means that if you are reading any one of those works, you’re substantially reading the same book: verbal acrobatics and eclectic invective, rather like Hergé’s Captain Haddock. He evolved a mesmerising style that makes him one of the greatest French writers — but then there was nowhere else to go. It’s like Beckett’s later prose works: marvellous, but you only need to read one.

Georges Duhamel, some ten years older than Céline, gets a couple of mentions from Catani, though he is somewhat cruelly labelled a ‘sociologist’. One of my favourite novelists, he is little known outside France and outrageously under-appreciated even there. His work preempts Céline, Albert Camus and Sartre in many impressive ways. Like Céline, Duhamel was a doctor, and wrote about his experiences in the first world war. But, unlike Céline, he was banned by the Nazis, and won the Prix Goncourt in 1918 for Civilization, his gentler, but equally despairing view of the war. The two would have merited close comparison, but you can’t do everything in one book.

Céline was self-centred and a fibber; he cared little for what others thought, but that didn’t stop him from endlessly whingeing. He was aggrieved about not getting the Goncourt, about his sales figures being too low and his ballets not receiving their due. His irascible correspondence with Gaston Gallimard, his last and remarkably patient publisher, contains some of his finest jetés.

The title of his celebrated novel promises an end to the night; but a more accurate title might have been ‘Journey to the Heart of the Night’. In his work the night rarely yields; there is some wit, some sardonic laughter at human folly, but the only fleeting delight is in language and the female form, especially the curves of dancers (many of whom he had relations with).

Journeys to the Extreme is comprehensive and lucid — though Catani has been very unlucky in that a huge trove of Céline manuscripts has resurfaced just in the past month. Increasingly, I find myself losing interest in learning about a writer’s maternal grand-father, but Céline is laid bare here for the curious reader or student.

The book is particularly good on the scandal of Céline being republished (it is amusing to see the convicted former French president Nicolas Sarkozy coming out to bat for him). Aside from the political iniquities, Catani argues that Céline wasn’t an unrepentant pessimist but a badly bruised optimist. It is hard to believe, as we are informed, that the razor-tongued Céline composed a ballet called The Birth of a Fairy.

Comments