First nights at English National Opera are, in the main, matters for a sociologist rather than an opera critic. That emphatically wasn’t the case with Wozzeck, but that is an acknowledged grim masterpiece, though still, nearly 90 years on, enough to put off casual opera goers and trendies. But the succession of vacuous new works that ENO has mounted in the past few years has attracted audiences, at any rate first-nighters, of a kind that one doesn’t see at any other operatic performance. They arrive early to kiss and shout and drink champagne, they trickle into the auditorium very slowly, stopping for many hugs on the way to their seats, and their talk in the interval is about anything other than the performance they are at. Inexpert at spotting celebrities or other media persons, I rely on my guests to tell me who some of these people are, and am left none the wiser about why they are there, who invites them and what their reactions might be.

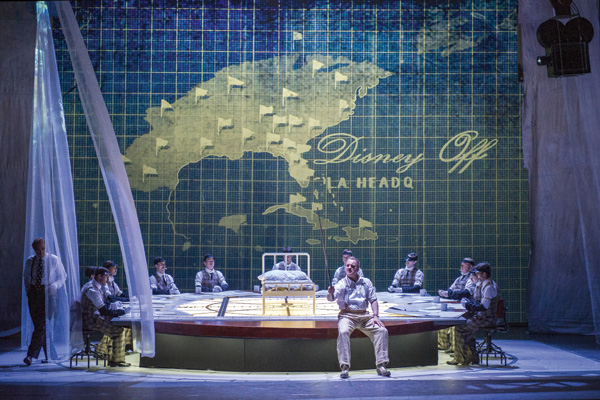

Philip Glass’s The Perfect American, his 24th opera (he has written another one since), was premièred in Madrid in January, and is now performed in London in collaboration with Improbable, ‘a place or a set of values as much as a company’, we are told. This piece is adapted from a novel by Peter Stephan Jungk about the last months of Walt Disney, and the libretto is by Rudy Wurlitzer. Why an opera about Disney, one might wonder, and reflect that he was a moderately complex and more than moderately unsavoury person, so his decline and death might hold some interest; and the main focus of Jungk’s novel is that a disgruntled former employee of Disney, William Dantine, persecutes his old boss for having ripped off his, Dantine’s, ideas and never given him any credit, accusing him of being no more than ‘a mediocre CEO’. Disney confronts his animatronic Abraham Lincoln puppet in Disneyworld, and disagrees with him vehemently about civil rights, etc.

Starting to feel interested? I certainly wasn’t, the text being at such a level of prolix banality that no composer ever could have made it interesting; and Glass as usual seems to go to great lengths to bore his way into immortality. His music, he insists, is no longer the minimalism that it once was. But it is only a somewhat tarted-up version of it: there are luscious chords now, a big chorus that is almost enjoyable, fewer mesmerising repetitions. There is still nothing that comes close to being creative or in the least memorable.

For me, the saddest thing about the evening was the wasted talent of Christopher Purves, whom I have admired intensely in almost every role I have seen him in. Not only is he wasted as Disney, with nothing interesting to say or sing or do, but what I have always found to be a commanding stage presence has temporarily deserted him. He even has a dreadful American accent, which disappears for minutes on end, and one can only hope that he finds the role so unrewarding that he is incapable of using his extraordinary gifts on it. But that wouldn’t be like him. The rest of the cast do what they can with what they are given, and in the case of John Easterlin as Andy Warhol attempt to do a good deal more, with embarrassing results. I’ve often wondered whether, if Glass went on doing what he’s made his name from for long enough, suddenly the whole phenomenon might collapse from inanition, and perhaps this is the point at which it will happen.

Handel’s Imeneo, one of his shortest operas — he called it an operetta, but somehow the term just won’t fit -— was produced at the London Handel Festival two and a half months ago, and though the modish updating and unsparing use of suntan lotion was irritating, on the whole it was a success. At the Barbican it was given a concert performance under Christopher Hogwood, and seemed very flat. If the temperature in the hall had been at least 15 degrees lower it would have helped; amazing that the performers didn’t flag under such sauna-like conditions. But it is anyway a comparatively weak piece, though it is purely about who loves, or at least will choose, whom, without any distracting politics.

The character with the most exciting music is the loser Tirinto, suitor for the hand of Rosmene, and Renata Pokupic dispatched his (her) arias with tremendous force. The successful suitor was taken by Vittorio Prato, the latest barihunk, and an interesting singer. Lucy Crowe, singing the confidante Clomiri, arrested attention as much as her mistress Rosmene, sung by Rebecca Bottone. Like The Perfect American, it lasted for just under two and a half hours; it felt much shorter than Glass’s piece, but not as much shorter as it should have done.

Comments