Paula Rego’s 2021 retrospective at Tate Britain demonstrated that, among art critics, ambiguity is still highly prized as a measure of merit. Martin Gayford: ‘No one, including its creator, can be aware of everything that’s going on.’

Laura Cumming at least gave examples. Of ‘The Cadet and his Sister’ (1988), she commented: ‘Bondage – physical, emotional, familial – is always in the air.’ The adjectives in that nervous parenthesis are insurance, the critic spreading her bets. The picture shows an older, bigger sister, formally dressed, with her cadet brother in uniform, wearing white ceremonial gloves. Behind them, a careful vista of trees. The painting depicts a milieu of public formality. Except that she has removed her gloves to tie his shoe laces. The gloves are off, laid on the ground, the nearest disclosing its red inner lining. Her handbag, also open, hints at its interior. We are glimpsing… something. In the left foreground is a small cockerel, a symbolic pullet. The sister and brother are avoiding eye contact. She is looking down at the shoe. He is looking away. It is a painting of denial, even as the deed is done. Obviously, this is a depiction of the induction of a trainee, a cadet, by an older person – a suggestion, an innuendo, all the more potent because of the poker-faced public front and the private message which is casting its shadow, like the handbag and gloves. That particular charged piquancy found on the border of respectability and the furtive excitement of sexual repression. It isn’t taking place as it actually takes place.

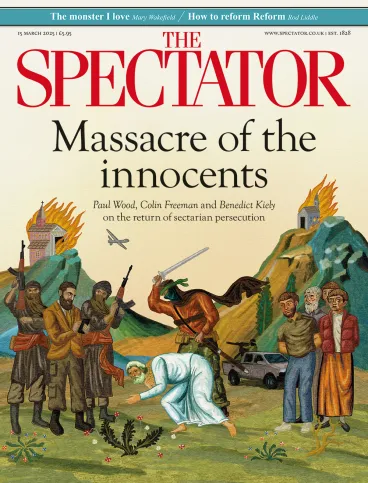

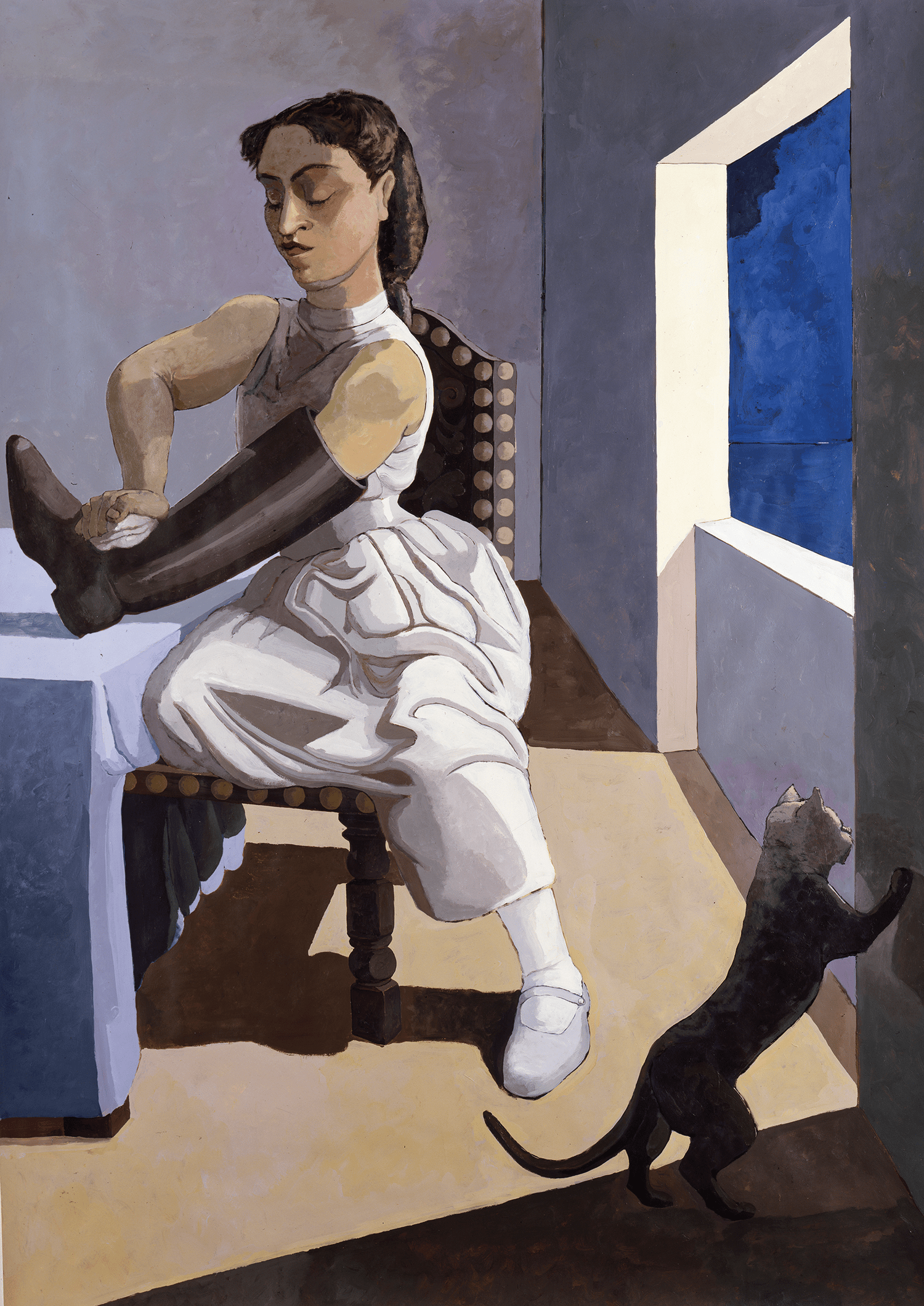

‘The Policeman’s Daughter’ (1987) is a reversal of power, according to Cumming, because her left arm is in the policeman’s boot. She, therefore, seems to be in control. I think, though, that the painting is about fisting and subservience. In the right foreground, a cat, a pussy, is on its hind legs, stretching. (You can find the same iconographic stretching cat in Hogarth’s ‘A Harlot’s Progress’.) In the ink and wash study, there is no cat, the girl is dramatically younger, and there is a toy castle in the foreground, castellated, gate closed, protected, vulnerable, miniature. Neither arm is inside the boot. Two different artworks, saying very different things. One innocent, one experienced.

The depiction of sex in painting isn’t the same as the depiction of nudity

The depiction of sex in painting isn’t the same as the depiction of nudity. Nudity tells us about unexciting externals only. By now its batteries are flat. How do we know that Manet’s ‘Olympia’ is a courtesan, a grande horizontale? A maid brings her a bouquet. She isn’t a streetwalker. She has a black velvet bow around her neck – a sophisticated inflection of innocent nudity – and her left foot is inserted into a lolling fur-trimmed mule, an image of casual intercourse. There is a black pussy on the foot of the bed. The other right foot is out of its mule, the toes just visible. So, in and out…

David Hockney’s ‘A Bigger Splash’ (1967) is one of a trio, ‘The Little Splash’ (1966) and ‘The Splash’ (1966). They were all painted from a photograph: ‘It takes me two weeks to paint this event that lasts for two seconds. The effect of it as it got bigger was more stunning – everybody knows a splash can’t be frozen in time, it doesn’t exist, so when you see it like that in a painting it’s even more striking than in a photograph.’ Apart from it being a tour de force of representation – the virtuoso capture of something ephemeral – what does the painting mean?

You might say the painting was an implied stay against mortality. Or you could say, more plausibly, that the painting is about loss – because the person who made the splash (there is a diving board) is no longer there. In Jack Hazan’s film about Hockney, A Bigger Splash, the painting becomes, in retrospect, about the break-up of Hockney’s five-year relationship with Peter Schlesinger in 1971. He is the absent presence. The bigger splash is the memory of Schlesinger: ‘And then I realised that he was having an affair with someone else. At first I was a bit hurt… it had probably got a bit boring sexually for both of us.’ But when ‘A Bigger Splash’ was painted in 1967, the relationship was at its beginning.

Hockney is painting not only water, but also ejaculate

There is a secret interpretation to these three paintings of the splash – Hockney is painting not only water, but also ejaculate. What is more, the particular painting is related to Hockney’s later comment about sexual boredom. In Nina Raine’s play Stories, the gay sperm-donor volunteers this pertinent information about quantity: ‘Well, it depends, really, on how turned on I am.’ An observation most men would confirm. As well as velocity. So, a bigger splash would correspond to greater sexual excitement when Hockney met Peter Schlesinger. There is, too, the smell of semen – that swimming-pool smell identified by Martin Amis in The Rachel Papers. Ejaculation, it’s everywhere. In Jen Hadfield’s poem, ‘Still Life with the Very Devil’: ‘Under the broiler,/ turned sausages ejaculate.’ In my poem ‘The Gift’: ‘the ejaculate salmon’. This thing that lasts for two seconds.

David Hockney 25 is at the Fondation Louis Vuitton from 9 April until 31 August. Paula Rego: Visions of English Literature is at the Lightbox Gallery, Woking, until 8 June.

Comments