One of the most depressing vignettes in Michael Vatikiotis’s agreeably meandering account of his cosmopolitan family’s experiences in the Near East is when he, a former journalist with a sharp eye for detail, visits El Wedy, close to the Nile south of Cairo, where just over a century ago his great-uncle Samuele Sornaga built a hugely successful ceramics works employing 200 people.

The factory no longer exists. It was nationalised, privatised, closed, and is now a vast construction site. After being harassed and prevented from taking photographs, Vatikiotis discovers it’s being developed as a resort — not for general tourists, mind, but for the army, whose presence looms menacingly everywhere.

Sornaga was from the Italian-Jewish (his mother’s) side of the wider Vatikiotis clan which first came to Egypt in the 19th century. The other more modest branch (his father’s) is Greek, Orthodox in religion, and its members emigrated to Palestine. Both places were then under Ottoman rule, but economic opportunities abounded, particularly in Egypt, where the Khedives were eager to modernise. The eastern Mediterranean was a region to hasten towards, rather than flee from.

Alexandria was usually the first port of call, at least for Italians who grew rich from the demand for technical expertise. Samuele’s grandfather, from Livorno, set up a ginning factory at a time when the American civil war fuelled a demand for Egyptian cotton. His uncle, Michael’s great-grandfather, helped establish the Egyptian postal service (whose first stamps were printed in Italian).

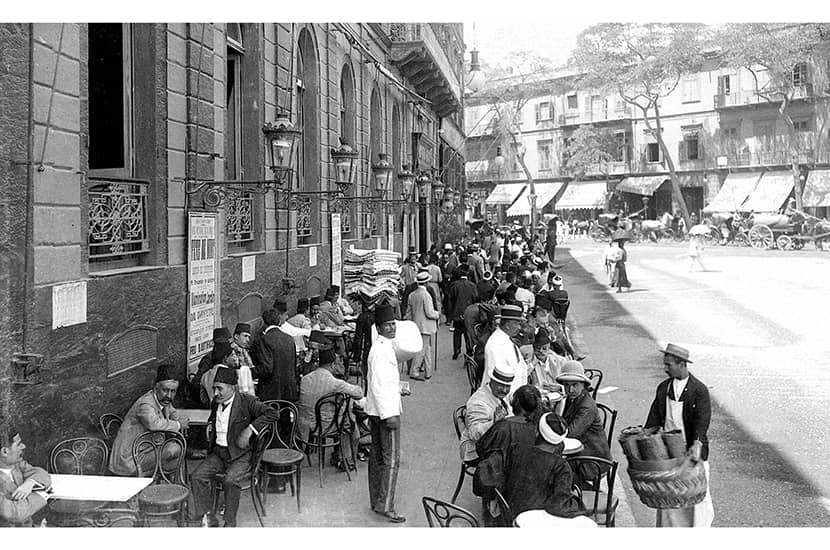

By 1864 one third of the city’s population was European, many of them Jewish. Lawrence Durrell described it in Justine as a melting pot of ‘five races, five languages, a dozen creeds’, the epicentre of a distinctive Levantine culture which Vatikiotis seeks to bring into focus.

Palestine offered the twin attractions of trade and religion. Vatikiotis’s great-grandfather Yannis left the Greek island of Hydra for Acre, once a crusader port, now in Israel, where he worked as a merchant seaman, then as a ship’s chandler. He died a pauper, but his son Jerasimous attended a good school in Jerusalem, and later, as a clerk working for Palestine Railways, married a woman from Rhodes with strong links to the Holy Land through two uncles who were Greek Orthodox monks.

After the first world war and the demise of the Ottomans, the ground changed. As nationalist noises intensified, the Italians in Egypt learnt not to flaunt their wealth, even if they still sipped lemonade at Groppi’s coffee house in Cairo. The Greeks in Palestine had lowlier, often bureaucratic, jobs, which made them more beholden to the hapless British trying to keep the peace between Jews and Arabs.

Seeking to explore all the places associated with his family, Vatikiotis offers graphic descriptions of modern Cairo, with its crumbling neoclassical buildings from the belle époque. Across the border in Israel, he interviews the Greek Orthodox patriarch who tells him chillingly that his is the only authentic Christian faith because it’s built on ‘righteous stones’ centred on Christ’s burial place in its Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Amazingly the Orthodox Greek church still owns a third of old Jerusalem, including the land on which the Knesset and prime minister’s office stand.

Vatikiotis got his British underpinnings when Lidia, Samuele Sornaga’s sister, married the mild-sounding Richard Mumford, who had been secretary to St John Philby, Kim’s father, in Transjordan. Their daughter subsequently married Michael’s father Panayiotis Jerasimof (P.J.) Vatikiotis, who, as a professor at the School of Oriental and African Studies, wrote the then definitive history of modern Egypt in 1969. P.J.’s early years in Palestine brought him friendships with local Arab nationalists, including Wadie Haddad, later a notorious guerrilla leader.

Vatikiotis acknowledges these Levantines were stuck uneasily between two or more worlds, not least when they tended to support the Axis in the second world war. (It’s fascinating to learn how Samuele Sornaga called on his friendship with the Egyptian royal family to take refuge at his El Wedy factory as Rommel advanced across the Western Desert.)

Yet Vatikiotis remains nostalgic for Ottoman times, when he fondly believes a spirit of cosmopolitanism existed. One manifestation was the Capitulations, the system which allowed foreigners in Ottoman lands to trade, pay taxes and deliver justice according to their own laws. He argues that this preserved a sense of autonomous communities, and so contributed to Levantine multiculturalism. The British, with their ‘effete’ public-school sensibilities, messed things up by drawing divisive lines in the sand, and the damage was later compounded by fundamentalist strands of Judaism and Islam.

In such matters Vatikiotis is quietly opinionated, a quality which makes him an admirable guide for this evocation of an era — a journey of personal discovery, where, despite complexities (a family tree would have been welcome), everything stands neatly in historical and topographical context.

Comments