Vladimir Putin notoriously declared the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989 to be one of the greatest disasters of the 20th century. However, as Revolution: Russian Art 1917–32 — an ambitious exhibition at the Royal Academy — helps to make clear, the true catastrophe had occurred 82 years earlier, in 1917.

Like many of the tragedies of human history, the Russian revolution was accompanied, at least in the early stages, by energy, hope and creativity as well as by murderous cruelty and messianic delusion. The greatest symbol of the last was Vladimir Tatlin’s huge projected ‘Monument to the Third International’ (1920), a sort of communist successor to Bruegel’s ‘Tower of Babel’, much higher than the Eiffel Tower and intended to house an international government of the entire globe.

‘We are now experiencing an exceptional epoch,’ proclaimed the artist El Lissitzky. ‘A new, real and cosmic birth in the world within ourselves enters our consciousness.’ He and many others welcomed the Bolshevik uprising, believing that revolutionary art could help create a new and

better society.

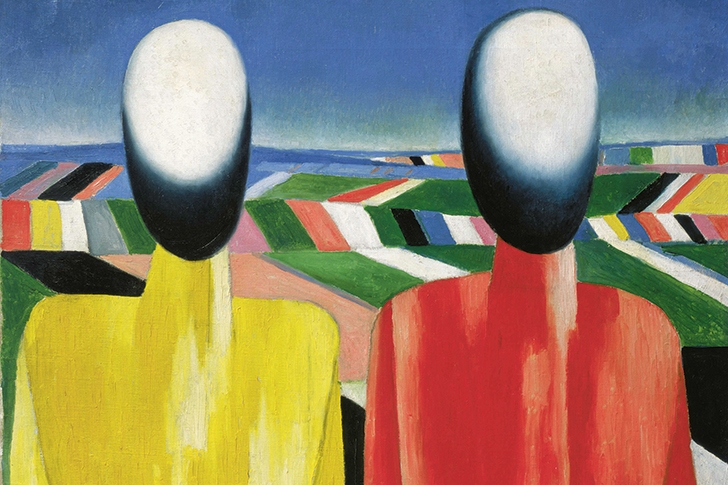

They were wrong. Revolution starts with a survey of Soviet art held in Leningrad/St Petersburg in 1932, a point when the avant-garde ferment was being suppressed and the era of Soviet realism was beginning. Consequently, a lot of what can be seen on the walls of Burlington House is disappointing. The good paintings dotted through the show are by familiar giants of modernism — Malevich, Kandinsky, Chagall (the last two escaped to western Europe early on). A room devoted to a figurative artist, Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, who is little known in the West only half convinces: on this evidence he was an interestingly idiosyncratic painter of still-life, but feeble when it came to people.

On the other hand, bad art can be as illuminating, historically, as good art. Thus Isaak Brodsky’s stagey painting ‘Shock-worker from Dneprostroi’ (1932) is a reminder of the way in which, by a neat Marxist irony, the Soviet system was undermined by its internal contradictions. It presents a splendidly muscular figure, like one of Michelangelo’s ignudi from the Sistine Ceiling (a shock worker was one who exceeded the norms of effort and production), perched high on a gantry of girders. He is engaged in the creation of the Lenin Dam — then the world’s largest and Stalin’s own brainchild — on the Dnieper River. This was not only colossal, but massively misconceived.

In his book Adapt, Tim Harford relates how the flaws in this prestige hydroelectric project were presciently analysed by a brilliant Russian engineer, Peter Palchinsky. The resulting flood plain flooded so much prime agricultural land that an equal amount of electricity could have been generated, much more cheaply, by growing hay and burning it in a power station. Ten thousand farmers had to be relocated, the labour conditions — romanticised by Brodsky — were appalling and the ecological effects disastrous. ‘The Revolution,’ the art critic Nikolai Punin confided to his diary as early as 1919, ‘is most wonderful for its lack of logic.’

One factor that doomed the Soviet avant-garde was the discovery that photographic media were much more effective at propaganda than abstract art. The camera is very good at lying. But in a painted portrait by Brodsky from 1927 Stalin looks exactly what he was: a malign thug.

The exhibition is full of images and objects that evoke the first decade and a half of the Soviet Union. Many of these are entertaining, even delightful — particularly the porcelain turned out by the ex-imperial workshops, sometimes with designs by Malevich himself. These are wonderfully paradoxical: luxurious objects decorated with geometrical abstractions symbolising the advent of a brave new world.

The photographs of heroic workers and their gleaming machines are often powerful, though also deeply misleading. So, too, are the excerpts from films of happy peasants and ardent revolutionaries. Mind you, the current fashion for showing clips of moving images in this kind of show makes for an unsatisfactory visual mix: they give only tantalising snatches of the movies, but nonetheless tend to upstage static exhibits.

Only occasionally does the true harshness of Soviet life come through. One object that suggests it is a reconstruction of Tatlin’s ‘Letatlin’ (1932), the name being a combination of the artist’s name and the Russian verb ‘létat’, to fly. This is a would-be man-powered glider, closely resembling Leonardo da Vinci’s impractical inventions. It symbolises both the impulse to soar into freedom and its futility. Tatlin was subsequently declared an ‘enemy of the people’, though he survived and died in obscurity.

He was one of the fortunate ones. The engineer Palchinsky, so right about the Dnieper Dam, was arrested by the secret police and shot for, among other crimes, ‘publishing detailed statistics’. His fate was shared by many of the most talented people in Russia. The celebrated theatre director Vsevolod Meyerhold, several portraits of whom are on display, was tortured and executed in 1940.

Osip Mandelstam wryly noted that nowhere was poetry more respected than in the Soviet Union: ‘There’s no place where more people are killed for it’ (he was to be one himself). The critic Punin looks worn and weary in a poignant portrait by Malevich from 1933. Eventually, he was arrested in 1949 for remarking that the innumerable portraits of Lenin that infested the country were tasteless. He was sent to the Gulag, where he died.

One of the most memorable exhibits comes at the end of the show: a room in which a series of prison photographs of victims are projected, one after another. The mugshots of Punin from his personal investigation file as prisoner — shaven-headed, crushed, prematurely aged — bring to mind the fate of Winston Smith in Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Tim Harford put his finger on a central failure of the regime created by Lenin and Stalin: a ‘pathological inability to experiment’. The Soviets, Harford argues, ‘found it impossible to tolerate a real variety of approaches to any problem’. So it proved in the arts.

Comments