The joint exhibition of Michelangelo Buonarroti and Bill Viola at the Royal Academy is, at first glance, an extremely improbable double act. Viola is one of the contemporary-art stars of the later 20th and early 21st centuries. He was one of the first to achieve fame in the new medium of video art, and is still its best-known exponent. While Michelangelo, as they say in showbusiness, needs no introduction.

But there’s more to this bromance, across eras and continents, between a 16th-century Florentine and a contemporary Californian than might immediately be apparent. The more you think about the pairing, and follow the argument of the curator Martin Clayton, the more analogies between the two appear.

Clayton, who is the head of prints and drawings at the Royal Collection, describes how in 2006 Viola paid a visit to the print room at Windsor, where one of the world’s greatest arrays of old-master drawings is kept. He had come to see the Leonardos most of all, but was overwhelmed by the Michelangelos.

Well he might have been. I had the same experience a few years later, when working on my biography of Michelangelo. I, too, sat down in the print room at Windsor and had box files full of astoundingly beautiful works put on the table in front of me. There was as much of Michelangelo’s invention compressed on those sheets of paper as can be seen on the Sistine ceiling.

Many of the drawings I held that day are on show at the RA. The ones made as gifts for Tommaso de’Cavalieri, the love of Michelangelo’s life, are there — and to see them is worth the price of admission in itself. These are works and subjects that were selected by the artist; no pope or Medici patron was involved. In this way, they are like most modern works of art: a pure expression of the artist’s ideas and imagination.

Michelangelo chose to draw ‘Tityus’ (1532), the naked giant condemned to have his liver eternally devoured by a vulture — a punishment for carnal love — and ‘The Fall of Phaeton’ (1533), a warning against hubris and an opportunity for an extraordinary visualisation of the horses that pulled the sun god’s chariot tumbling through the air in a variety of positions, hooves flailing.

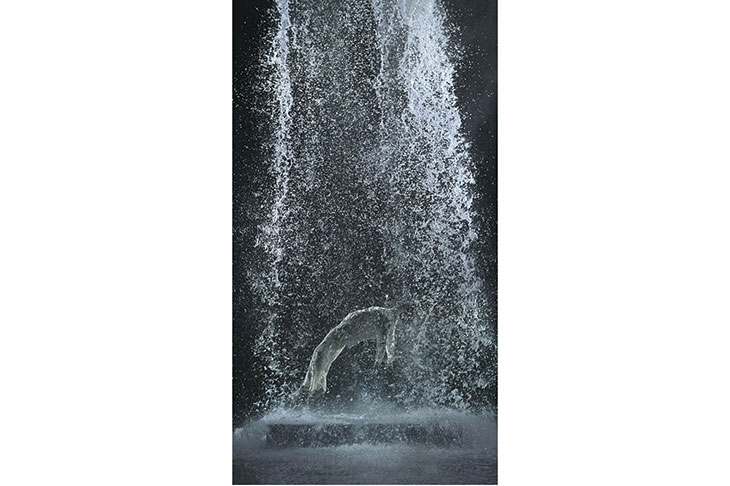

For the most part, however, Michelangelo’s images are of human figures, often naked, whose bodies alone carry the meaning and emotional force of the works. This was one of the deep affinities between his own art and the Renaissance master’s that Viola apparently saw that day. He seldom tells a story, but rather presents us with a figure such as the nude man in ‘The Messenger’ (1996), who rises from the watery depths, takes a breath and sinks back down again. In ‘Tristan’s Ascension’ (2005) a clothed figure rises from a slab amid a sparkling torrent like a waterfall.

Michelangelo did not share Viola’s obsession with water and immersion (traceable to the latter’s near-drowning as a child). But the link between Viola’s aerial visions and Michelangelo’s drawings of the resurrection, in which Christ shoots upwards from the tomb, is obvious. Both find ways to express spiritual matters in visual terms. In the late drawings of the crucifixion on show, done in 1560–4, when Michelangelo was approaching 90, Christ, the Virgin and St John seem to be dematerialising before our eyes.

I agree that Viola belongs, at a great distance in time, to the tradition of Michelangelo. What he does follows on more directly from late 19th-century artists such as G.F. Watts, who painted spiritual allegories with Michelangelo-esque nudes. Indeed, what I like about Viola is that he’s so evidently part of what David Hockney has called the history of pictures.

But, and it’s an important qualification, these affinities are best understood in a text. What you see at the Royal Academy amounts to two separate exhibitions in parallel — a big one of Viola, effectively a retrospective, and a smaller one of Michelangelo. Nor do they co-exist harmoniously.

Viola’s ‘Nantes Triptych’ (1992), which includes footage of a woman giving birth and the artist’s mother dying, is so forceful that it is hard to give proper attention to the marble ‘Taddei Tondo’ and chalk drawings on the opposite wall. I looked at the exhibition with members of the public, almost all of whom seemed gripped by these images of fleeting mortal existence. Elsewhere, it is Michelangelo’s supreme drawings that pull the eye away from the video gleaming in another part of the same gallery.

The medium really is part of the message, and high-definition, wall-sized video projections and small-scale hand-draughtsmanship are just too different to experience comfortably together, or even one after another. The words of an ancient lyric drifted into my mind: ‘’Tain’t what you do (it’s the way that you do it)’. The aims of Viola and Michelangelo may be comparable, but the results are distinctly incompatible.

Comments