For years, each school in England has been put in one of four categories: ‘outstanding’, ‘good’, ‘requires improvement’ and ‘inadequate’. While undoubtedly crude, the system offered clarity to parents. Bridget Phillipson, the Education Secretary, has now abolished this categorisation structure but not yet said precisely what will replace it. Children are returning to school in the middle of uncertainty.

Are politicians blind to the staggering inequality within a state system that educates 93 per cent of pupils?

The National Education Union has long urged schools to ignore Ofsted ratings and to stop referring to them on their gates. Phillipson’s reform seems to nod towards this. But instead of abolishing Ofsted, as the union wants, she should supercharge it – giving it more resources so inspections can be less fleeting, with more follow-ups and advice. Given that a child’s prospects can depend on their school’s performance, it’s clearly vital for parents to know as much as possible.

When a school writes its own report, there is too great a temptation to choose deceptive metrics. If, for instance, a school judges itself on the percentage of pupils who achieve top grades, it may rig this by discouraging certain children (especially those from disadvantaged background) from tackling harder subjects. Deplorably, it can also fix results by kicking out well-behaved pupils who they fear will lower their A-level score.

So how are parents to find the full picture? To this end, The Spectator has released a new online tool showing the complete A-level results for every school in England, state and private. Every grade in every subject is there, together with a comparison to other local and national schools. You can find it at spectator.co.uk/results and at the end of this article.

In The Spectator schools supplement, published with the magazine this week, we also name the 80 schools whose pupils receive the most offers from Oxford and Cambridge. Interestingly, 51 are state schools. When Michael Gove became education secretary, just over half of Oxbridge admissions were from private schools. Now, it’s less than a third. This reflects shifts in attainment. All over England, state schools are outperforming their private counterparts, helped by the Gove reforms. By toughening up the curriculum and allowing schools to break free of local authority control, Gove raised the ambitions and the results of both schools and pupils.

This is why it’s worrying to see Labour commission a curriculum review. Will they reverse reforms that have had such an obviously beneficial effect? A return to rigour and discipline may be unfashionable but has been working miracles in places like the Michaela Community School, run by Katharine Birbalsingh – one of the best state schools in England when ranked by how much pupils from all backgrounds improve. Labour’s task, surely, is not to unpick success but to focus on where the Tories failed.

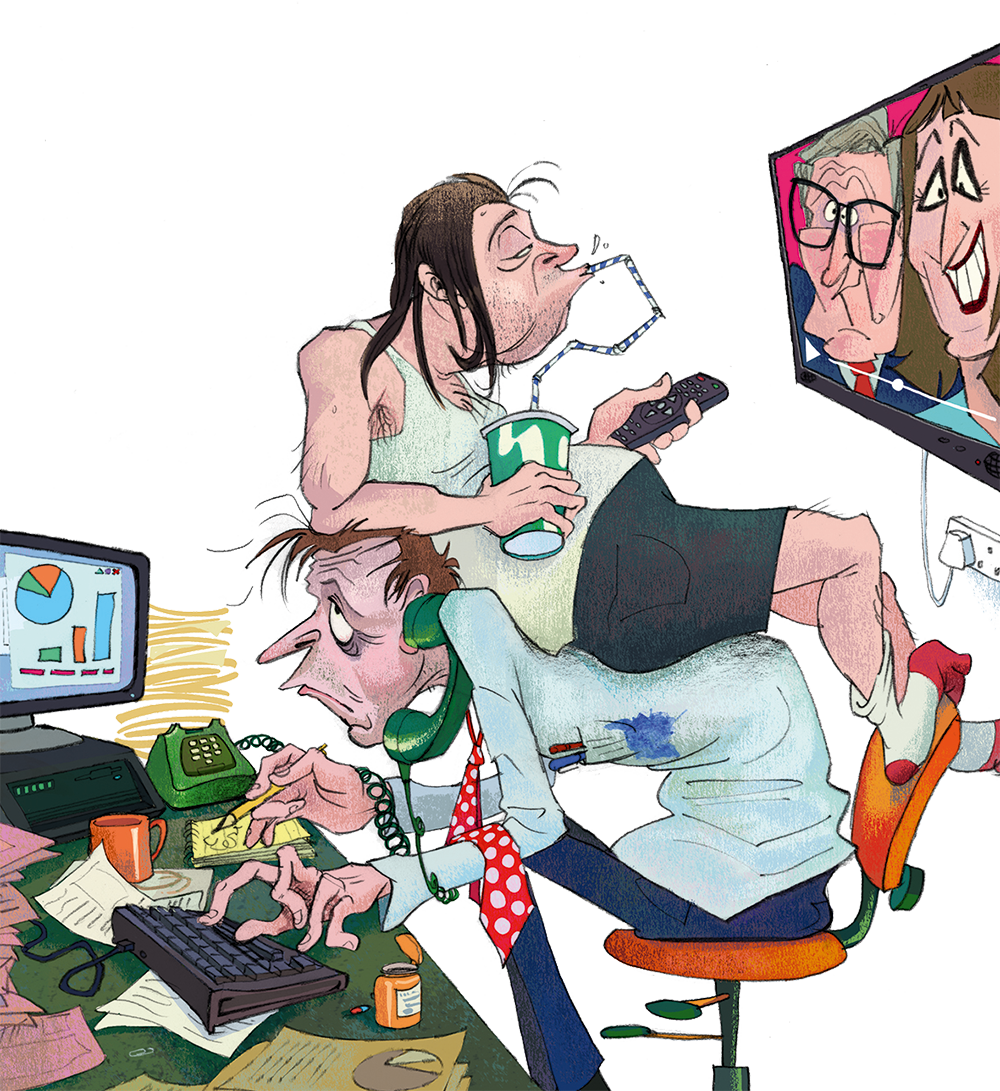

Labour’s only education policy so far has been slapping VAT on private schools. It’s no surprise to see Eton pass on this bill in full to parents. Such high-status schools could double the fees and still fill every place. The VAT change will affect parents who struggle to pay and many schools will be forced to either close or to stop issuing bursaries (such as the one Keir Starmer enjoyed). The PM will find it is not difficult to kick away the ladder his family once used. In politics, it’s easy to dismantle. It is harder to build.

The money generated by his VAT raid will amount to less than 3 per cent of the schools’ budget and do nothing to address the real problem: the scandalous disparities within the state sector itself. The Spectator’s results analysis shows that, while private schools are no longer in a class of their own, there is a shocking variety in the quality of state education – with a direct relationship to neighbourhood wealth.

Pupils in the most affluent neighbourhoods can attend state schools with outcomes better than the average private school. Those from middle-income families have middling results. Sink estates are saddled with sink schools. Why might this be? Are we to believe that children from poor backgrounds have less ability? Or might politicians – obsessed with Oxbridge and the rich – be blind to the staggering inequality within a state system that educates 93 per cent of pupils?

This is the cause to which Ms Phillipson should devote herself. There is no end of excellence in the state sector – if you’re rich enough. The crisis is in the communities with schools currently judged to ‘require improvement’ or be ‘inadequate’. Labour may abolish the words but it cannot abolish the concepts. How are such schools to be identified? Or is the idea that we just look the other way? It is still horribly unclear.

Starmer has made Britain the only country in Europe to tax education. He has ensured there will be fewer bursaries at elite schools for the sons of today’s toolmakers. But other than a pledge to increase the teacher headcount by 1.4 per cent he has announced no new help for any pupil in any school. If his legacy is to be anything other than knocking down what others built, he had better get thinking.

Comments