The Mesopotamians wrote on clay and the ancient Chinese on ox bones and turtle shells. In Egypt, in about 1,800 BC, someone even found the space to scrawl on a portable sandstone sphinx. Look closely towards the base of the sculpture and you will find a delicate line drawing of an ox head. Remarkably, this picture reveals the origins of the letter ‘A’.

At the first stage in its development, the ox was simplified, so that an engraver could express it with just a couple of lines. An Egyptian seal stone shows the animal’s head in abstract form. Next, the shape was flipped 90º, so that by the time the Greeks had adopted the Phoenician system of writing, in the 8th century BC, it was recognisably an ‘A’. Following some tinkering by the Etruscans and Romans, it was no longer possible to tell what was horn, and what jaw. ‘A’ was no longer for ox.

Writing probably first developed in Egypt, China, Mesoamerica, the Indus Valley and Easter Island at a similar time, but the Mesopotamians of ancient Iraq have long been credited with its invention. The earliest examples of text from across the globe tend to be more functional than literary. A tiny cuneiform tablet records the distribution of barley to farm labourers in about 3,000 BC. A towering Mayan plinth from 7th-century Belize sets out a ruler’s family tree.

This superb exhibition does not so much walk as zigzag you through the history of writing. The display is arranged along diagonals in the basement of the British Library, which means that you hardly notice when you stop proceeding chronologically and slide hundreds of years back in time, as if in an exciting but highly intellectual game of snakes and ladders.

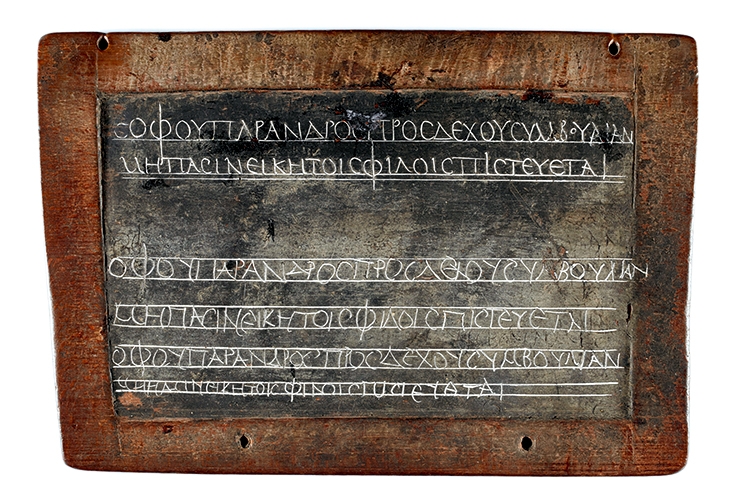

There are ancient wax tablets filled with writing exercises by schoolboys next to rigorous 18th-century handwriting manuals that instruct in ‘English Round Hand’. A Japanese ‘mirror of the hand’ calligraphy album, compiled in the 19th century, features writing samples by 8th-century emperors and decorative pages adorned with pen drawings and gold leaf.

Some of the loveliest objects on display come from the library’s own book collection. William Caxton’s first edition of the Canterbury Tales sits on one side of the gallery, and a collection of richly adorned Italian editions of classical literature on the other. Each of the publications has been chosen because it broke new ground. Venice-based publisher Nicolas Jenson’s splendid Cicero from 1470, for instance, is printed in elegant and rounded ‘roman type’. Most early printers up to then had opted rather for typefaces based upon gothic script. Just over 30 years later, Aldus Manutius, another of the titans of the early print industry, released a collection of Virgil’s works in a novel and suitably poetic italic typeface.

In the earliest days of printing, the Chinese had led the way. Already in the 8th century, they wove together the fibres of mulberry trees to create paper that was smooth enough to carry text. When the Arabs caught wind of their invention, they allegedly kidnapped the paper-makers in order to learn their skills. When it came to rendering so many curving characters in printable form, however, the Chinese and Arabs had to work that much harder. European alphabets lent themselves more easily to mass production. Even looking at a ‘Double Pigeon’ Chinese typewriter from 1975 you appreciate the nature of the challenge. The tray bed of the typewriter, popular in Maoist China, seems ready to burst with its 2,450 pieces of type.

As ingenious as these machines are, the simpler tools and books of handwriting in this show leave a more indelible impression. Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s quill pen is a pitiful thing with a broken nib, but immediately you picture it gripped tight in his industrious hand. He must have written it out of service. The diaries of Florence Nightingale are filled with handwriting so small and neat that you cannot doubt her meticulousness. As for James Joyce’s colour-coded page notes for Ulysses — chaos in every direction. There is no doubting which of the pages belonged to the writer. How would Joyce have coped with just a block of stone or piece of ox bone to work on? He’d never have finished.

Comments