Ken Burns made his name in 1990 with The Civil War, the justly celebrated 11-and-a-half-hour documentary series that gave America’s proudly niche PBS channel the biggest ratings in its history. Since then, he’s tackled several other big American subjects like jazz, Prohibition and Vietnam; and all without ever changing his style. In contrast to, say, Adam Curtis (another ambitious film-maker whose methods have remained unchanged for 30 years), Burns’s documentaries take an almost defiantly considered approach, forgoing anything resembling self-regarding flashiness in favour of such old-school techniques as knowledgeable talking heads, careful chronology and straightforwardly appropriate visuals.

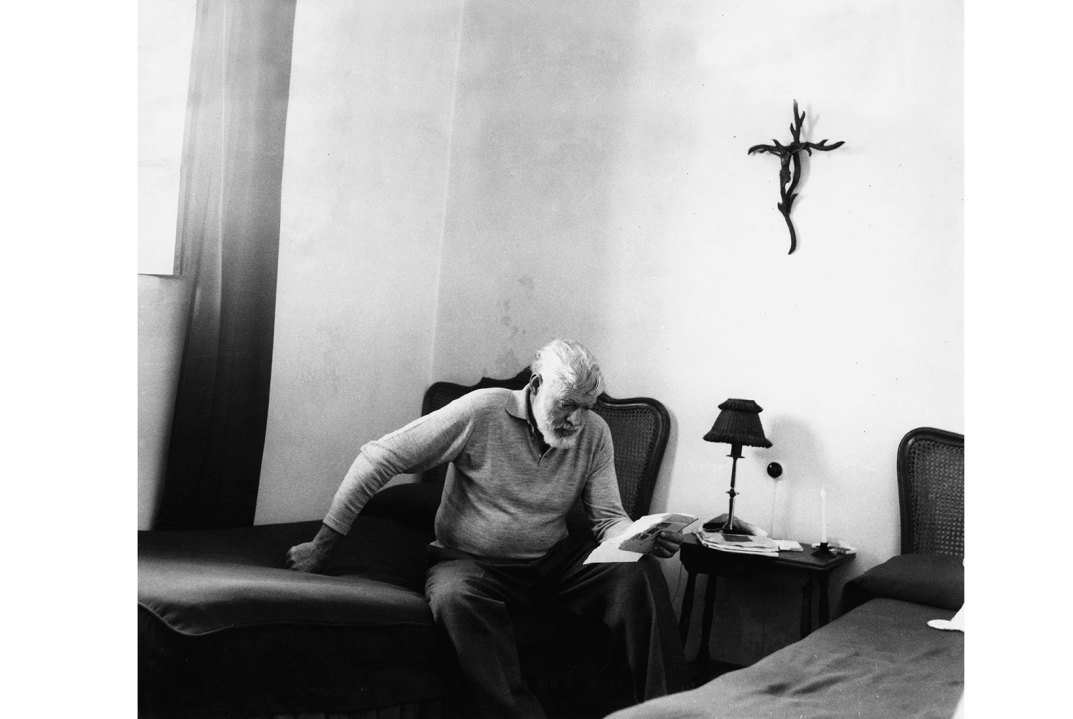

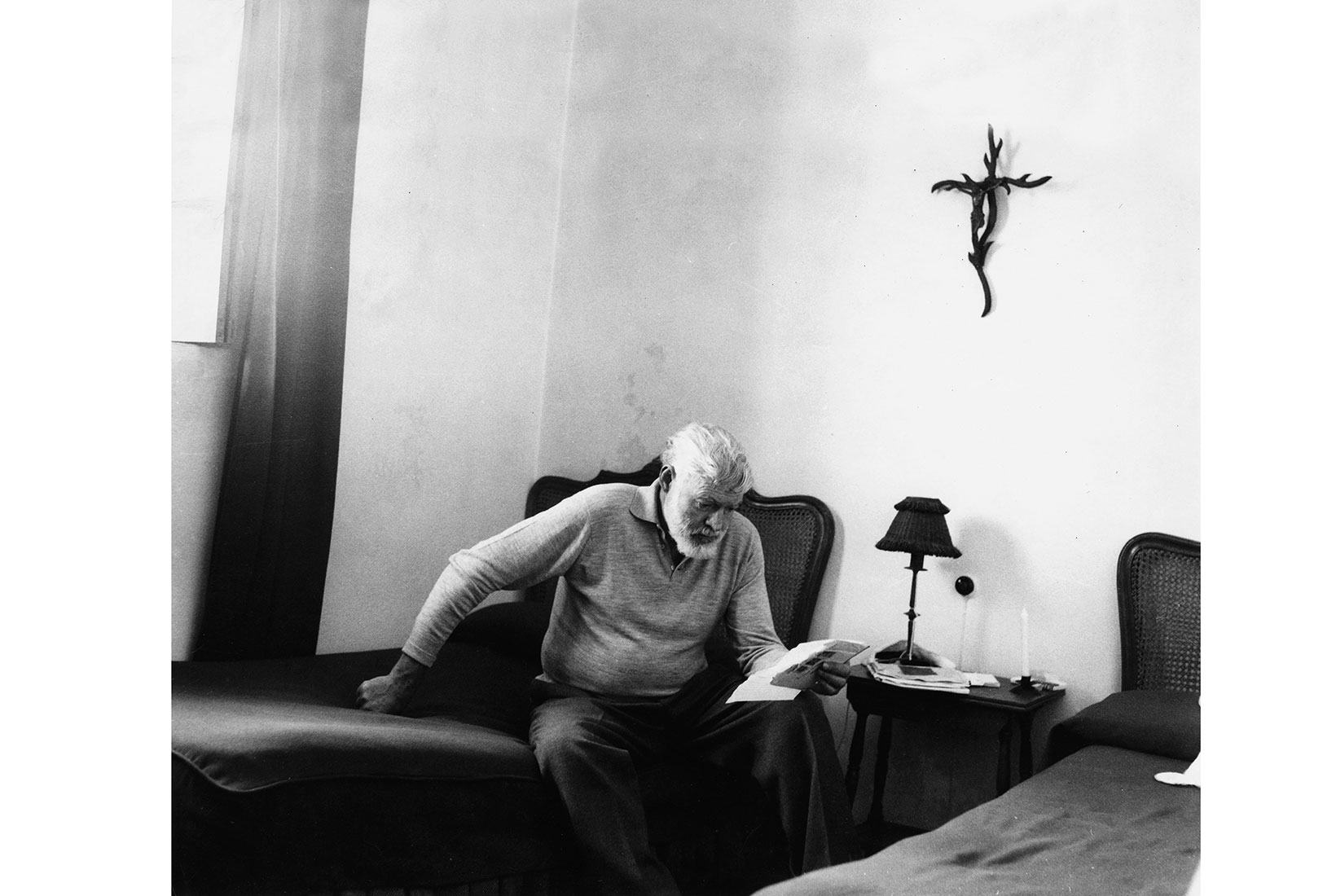

Hemingway, his new six-parter being shown on BBC4, duly fails to mark a radical change in direction. Burns’s regular narrator Peter Coyote declaims a thoughtful, impeccably researched script with due solemnity and a firm commitment to apposite quotation. A not-hugely-varied assortment of writers and academics (some captioned simply ‘literary scholar’) ponder Ernest Hemingway’s contribution to American letters. The photographs and clips match everything we hear with unfussy precision.

In contrast to film-makers like Adam Curtis, Burns takes an almost defiantly considered approach

Even so, the most striking similarity between Hemingway and Burns’s previous work is how right he is to have enough confidence in his subject matter to proceed with such unhurried aplomb. Or, in short, how great it is.

Of course, the sheer eventfulness of Hemingway’s life helps too. Brought up by a classic combination of depressed father and domineering mother in the Chicago suburbs, by the age of 17 young Ernest was already working for the Kansas City Star at a time when the city was convulsed by violent strikes. A year later, he joined a first world war Red Cross unit in Italy and was delivering cigarettes to the front line when a shell exploded close by, leaving him with more than 220 shrapnel wounds — and that was before his stretcher was machine-gunned. After the war, he headed with his first wife to Paris, then in its pomp as the centre of the cultural world, where he hung out with the likes of James Joyce, Ezra Pound and Gertrude Stein, pausing only to cover post-war Europe for the Toronto Star. By the time Tuesday’s episode ended with his decision to quit journalism and concentrate on fiction, he was still in his early twenties.

Along the way, the programme traced possible influences on Hemingway’s later prose — not least the Kansas City Star’s style guide: ‘Use short sentences. Use short first paragraphs. Use vigorous English.’ It also quietly busted a number of myths, including his lifelong claims that he was penniless — as opposed to quite comfortably-off — during his time in Paris.

All of which might have brought on a distinct nostalgic glow for any viewers old enough to remember when British television, led by Arena, used to make these kinds of lengthy, unashamedly high-minded literary profiles itself instead of importing them from the States. And if you needed further proof of how much things have changed, Channel 5 obligingly provided it — by broadcasting at the same time on the same night Brontë’s Britain with Gyles Brandreth.

In fact, this was by no means a bad programme of its kind: warm-hearted, entertaining and occasionally even informative. It’s just that, after Hemingway, it was a jolting reminder of how we now seem to prefer our books documentaries to be: celebrity-led, reinforcing the myths rather than busting them and with no great distinction made between novels and their television versions. (Talking of Anne’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, Gyles spoke the curious sentence: ‘One-hundred-and-fifty years later, the 1996 TV adaptation still has the power to shock.’) Above all, there’s the belief that no fiction writer ever makes anything up.

So it was that Gyles pretended that a ruin on Yorkshire Moors called Top Withins was once the ‘real’ Wuthering Heights. (Luckily, we weren’t shown the Brontë Society plaque there which unequivocally declares that ‘The buildings bore no resemblance to the house’ that Emily described.) Then again, so apparently was the nearby Ponden Hall — usually regarded by fiction-sceptics as the ‘real’ Thrushcross Grange from the novel, but here conscripted to be the ‘real’ Wuthering Heights too, complete with the very window at which ‘Cathy made her most unforgettable appearance’ (not bad going for the ghost of someone who was never alive in the first place). A little while after that, Gyles was shown the ‘real’ Thornfield Hall from Jane Eyre — and required to gaze wonderingly at the precise spot at which ‘Jane came to Norton Conyers’.

Granted, this desire for everything in our favourite books to be true could be seen as touching evidence of the power they have over us. Nonetheless, it was hard not to feel that Gyles was rather missing the point of fiction when he concluded triumphantly that, far from being mere ‘flights of fancy’, the Brontës’ novels are reassuringly autobiographical after all.

Comments