Of all the moronic decisions made by cultural organisations over the past 50 years, probably the most insulting and retrograde is the decision, in 2021, by Unesco to strip Liverpool of its world heritage status. Unesco said the development of the docks amounted to an ‘irreversible loss’. The regeneration of the waterfront, including the building of Everton’s new £500 million stadium, was blamed for destroying Liverpool’s ‘outstanding universal value’.

I walked up Liverpool’s Regent Road for half an hour to see for myself. Doing so took me through one of the most derelict wards in the country, the old docklands. I didn’t pass another human being for a good 20 minutes, only cars screaming. There was some majesty in the buildings. The Tobacco Warehouse is beautiful. And the Kingsway Tunnel Ventilation Shaft is one of the most overwhelming things I’ve ever stumbled across.

But Liverpool is not a museum. Unemployment is not heritage. To expect the people of Liverpool not to develop the docks is to forbid them from improving their city. I hate the redevelopment aesthetic as much as anyone – that horrible homogeneity of landfill modernism. Yet the alternative is having to accept a ghost town. The historic buildings should stand, but new ones must obviously be built.

The new Everton stadium, called the Hill Dickinson, is in the centre of the docks, and it is good. It suits the club that it was built for: it’s not showy, it’s decidedly mid-table. It looks a bit like a wifi router. The waterfront by the southern stand shimmers and reflects in the glass windows. Pleasingly, in the areas closest to the stadium, tables and chairs have been put up on pavements, as Rowan Moore wrote, ‘as if this were Naples’. This is gain, not loss.

The Hill Dickinson features in Tate Liverpool’s exhibition Home Ground: The Architecture of Football. But it’s not really an exhibition: it’s a room. The Tate Liverpool is closed at the moment so it has relocated to RIBA North. This isn’t worth travelling for at all, but go if you’re nearby. I left feeling that I’d somehow attended a magazine article. No bad thing.

The show makes it clear how tricky it is to design a football stadium. You can’t just repurpose any old stadium, as West Ham found out when they moved to Olympic Park in east London. The athletics track pushes the crowd offensively far from the pitch. The big dome, meanwhile, snatches any noise the crowd might try to make, and expels it out into nowhere. The surrounds don’t work either. You walk with West Ham fans across a canal and through a pretty little park – how is anyone meant to start a fight here?

The new Everton stadium suits the club that it was built for: it’s not showy, it’s decidedly mid-table

Tottenham Hotspur, at the cost of £1 billion, did it best. The first time I went to their new ground, I was staggered. The stands feel intimidatingly vertical. In those impossibly steep seats you’re miles away from James Maddison, yet you feel like you can see his sweat. Their rivals Arsenal, by contrast, moved to the Emirates from the gorgeous art deco stadium in Highbury 20 years ago. It’s such a soulless dump that they’re already having to redevelop it.

The exhibition takes us from the beginning of football to the present. They call it ‘the people’s game’, somewhat ignoring the fact that the first association football match was between Westminster and Charterhouse. No matter. Here is Archibald Leitch, a Glaswegian who designed 16 of the top 22 first division stadiums in the early 20th century. His big thing was the idea of double-decker stands (see below).

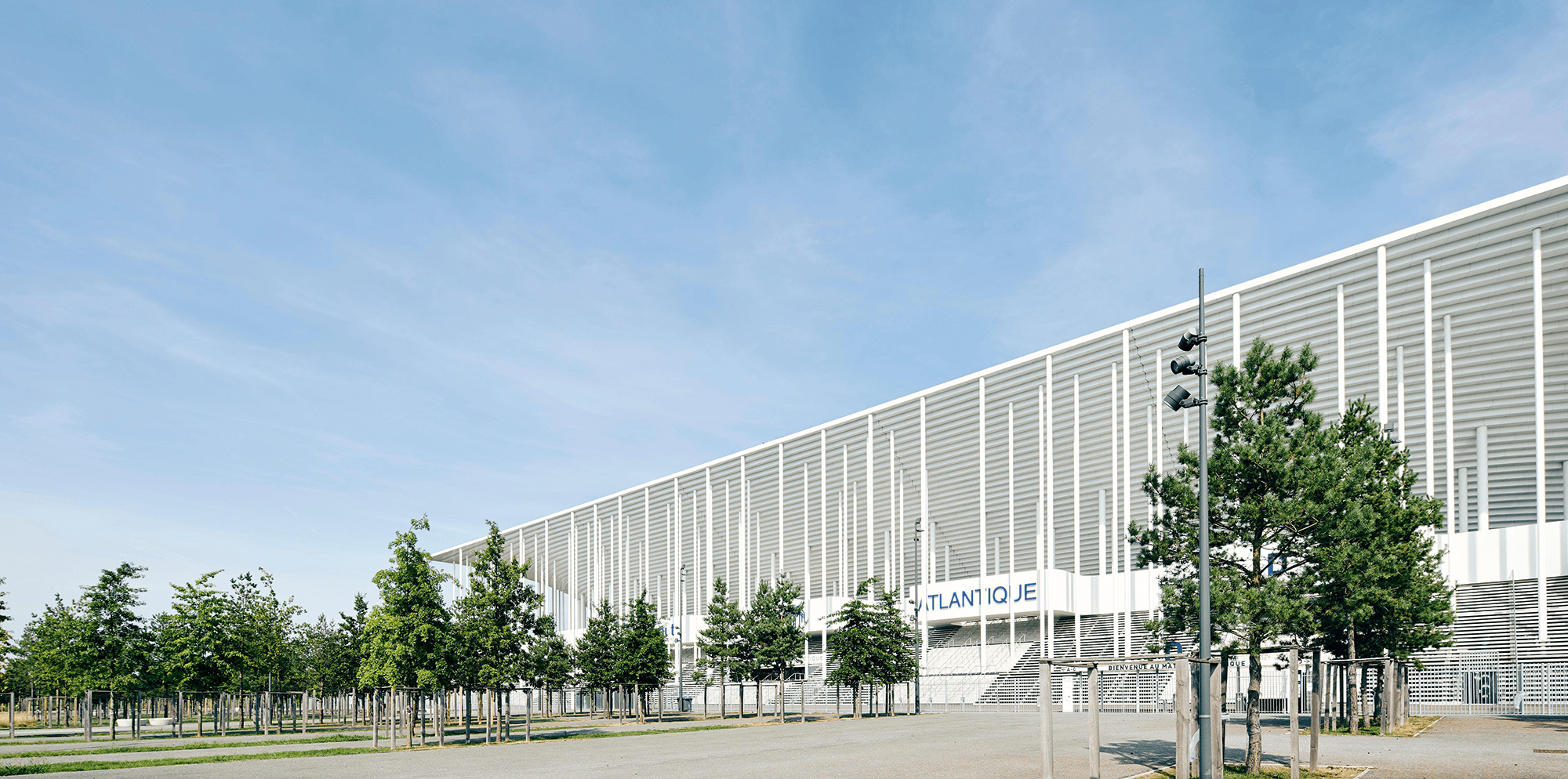

We’re then onto the brutalist turn of the 1950s, when economics and safety regulations demanded concrete. I had a nice stare at the Parc des Princes. The show dissolves at this point into loose themes, and you instead just marvel at some great photos of football stadiums. The colossal Maracana in Brazil, which once fit 200,000 spectators. The blimp-like Allianz in Munich. The Kirklees Stadium in Huddersfield, RIBA-certified. The deliciously French Stade Atlantique in Bordeaux.

Tate does a good job of reminding us of the importance of football stadiums, their church-like role. The exhibition is also convincing when discussing their architectural merit and cultural value. This is something that the city of Liverpool understands. And Unesco clearly doesn’t.

Comments