‘What is man, that thou art mindful of him?’ asks the Psalmist. It’s a good question.

God Himself doesn’t give a very satisfactory answer. In one breath he insists that humans are a little lower than the angels, made in His own image, but also (in a formulation as bleak and more terse than any modern reductionist’s) that they are made of dust, and to dust they will return.

Darwin tells us a similar story. We don’t have to flip back too many pages in our family albums, he says, before we see furry, feathered and scaly faces. But then he draws an exuberantly branching tree of life, rooted in stardust, and tells us that we’re perched on the topmost bough. It’s not surprising that we’re confused.

This confusion is at the bottom of all our neuroses. Our predominant feeling is the queasiness of ontological vertigo. We know ourselves too well, and read the newspapers too diligently, to believe that we’re gods. And yet our pride, and our love of literature and old churches, convince us that we’re not mere beasts. We see human deaths as more morally significant than animal deaths. We hold ourselves to different standards: we can tolerate cannibalism in wolves, but not in ourselves.

We’ll do anything to reduce the queasiness. That’s what our moral and religious and cultural and scientific lives are about. We read books, draw pictures and watch plays to try to describe ourselves to ourselves. We worship gods in us and gods outside us, trying to find some comforting affinity with the divine. We frenetically name animals in an attempt to feel, like the first animal-namer, Adam, that we have dominion; but also so that we can caress and relate. There are no unnamed pet dogs.

But nothing really works. We’re still amphibians: neither properly spiritual nor satisfactorily material. We’re never at home. We can’t romp, copulate or die quite like our dogs; nor can we thrive on light and abstraction.

Faced with the hopeless prognosis for our condition, a common palliative strategy is to try to forget our connection with the natural world; to hole up in cities; to eat plastic animals blithely, denying what they are; to have actual and metaphorical air-conditioning; to be animals only in the bedroom and the boardroom, and bloodless, besuited apologies for animals everywhere else. Yet this doesn’t work either. At some level, if only in our dreams, we know we’re wild things, and that we’ll only have functional relationships with ourselves and each other if we acknowledge what we are and where we’ve come from. And where we’re going, which is back to the wild. One day I’m going to be eaten by worms or fire, and so are you.

One way of asserting some reassuring control over the wildness out there — and hence the wildness in us — is to classify. Pigeonholing is anxiolytic. Adam did it, Aristotle did it, the medieval bestiarists did it, and then, from the 18th century (Linnaeus’ Systema Naturae was published in 1735), it became a popular, opioid religion, telling us what we wanted to hear about what we are. A few anarchic protestors (notably Swift, in Gulliver’s Travels) objected to the hubristic pedestal on which the taxonomists placed humans, but they have still not prevailed.

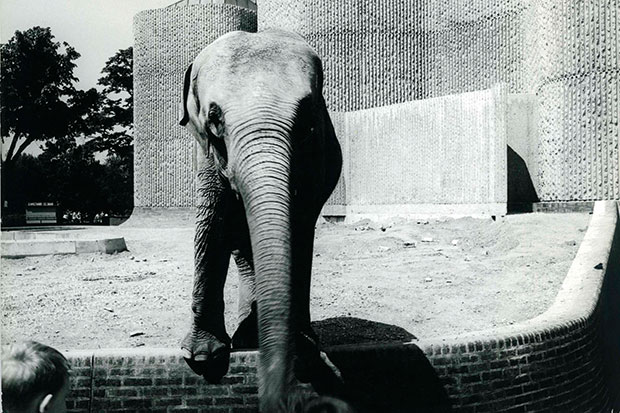

There are other emollients. We can collect, and tell ourselves that if wildness is stuffed and locked in a glass case, it won’t come out and get us. We can put strange and dangerous things in zoos, invite them electronically into our rooms, courtesy of David Attenborough, or embody them in soft toys with eyelashes like ours. There they’ll be safe, and so will we.

These are vast themes, normally thought of as too big or too scary to examine. It is hugely impressive that Making Nature, shortly to open at the Wellcome Collection, addresses them at all. That it does so with such steely, elegant, iconoclastic verve and nerve is astonishing.

Swashbuckingly curated by Honor Beddard, Making Nature is an exploration of the way that humans represent the non-human world — and hence how they see themselves in relation to that world. For (and to acknowledge this is the real genius of the exhibition) we are always self-creators: everything we paint is a self-portrait.

Beddard knows that the act of representation is political: that to juxtapose X with Y is necessarily to make an assertion about the nature of both, and to change both. She has a wry awareness that to hold an exhibition to highlight the distortions of taxonomy, control and display is to create a new set of distortions. That means that she has to subvert her own event. And, splendidly, she does. For me, the centre of the exhibition is Hiroshi Sugimoto’s eloquently ironic picture of a museum diorama. To make artifice into art is smart and unnerving.

It’s a small exhibition: there are just over 100 objects, many of which are images. But the ground is well covered. There are pedigrees, drawers of bird skins, comparisons of human and animal faces, glass-eye catalogues, ethereal seaweeds (like their own Platonic forms), an interrogation of the notion of ‘type specimens’, and there’s plenty of mere exuberant weirdness. Our thirst for patterns and metanarratives is gently exposed — most beautifully in Werner and Syme’s 1814 catalogue of colours in different natural domains: the same ‘buff orange’ is said to recur in the ‘Streak from the Eye of the Kingfisher’, the stamen of the large white cistus, and the mineral natrolite.

This is a bracingly philosophical exhibition: a rigorous exposition of the phenomenologist’s axioms that context matters profoundly, and that each of us creates a universe. If you know you’re a wild thing, go along to meet some more of the family and to see what others think of them — and so of you. If you don’t know you’re a wild thing, go along to realise that you are.

‘The most dangerous worldview,’ wrote von Humboldt, ‘is that of those who have never viewed the world.’ ‘Or themselves,’ I’m tempted to add. But my addition is unnecessary, as Making Nature so brilliantly shows.

Comments