Sir John Lavery has always had a place in Irish affections. His depiction of his wife, Hazel, as the mythical figure of Cathleen ni Houlihan, which appeared on the old ten shilling and subsequently on the watermark of the Irish pound notes, meant, as the joke went, that every Irishman kept her close to his heart. He was indeed Irish – born in Belfast – but was at home in Scotland, and was the best known of the spirited group of painters called the Glasgow Boys. Yet he lived most of his life in London, was friends with Winston Churchill (they took a painting trip together) and also with Michael Collins, the Irish Nationalist, with whom Hazel was, ahem, close. If ever there were a man who embodied the interconnectedness of Britain and Ireland, it was Lavery.

The thing about Lavery was that he started poor, very poor – and he never glamorised poverty

But France loomed large too. He trained in Paris, hero-worshipped the naturalist Jules Bastien-Lepage and was part of the cosmopolitan group of artists who congregated at Grez-sur-Loing in the 1880s, where every laundry maid must have been stalked by men with canvases. There’s a lovely picture by Lavery of ‘The Bridge at Grès’ (1901), showing the play of light on a stretch of the river.

That painting comes at the start of a splendid exhibition of his work at the National Gallery of Ireland in Dublin, which, appropriately, will then travel to Belfast and Edinburgh. It’s called Lavery. On Location, and there were a bewildering number of locations – France, Ireland, Scotland, Tangiers (where he wintered for decades), Germany, Switzerland and, at the end of his life, New York and California. The man who began as a naturalist with impressionist ways – painting outdoors, obsessed with the play of light on surfaces and focusing on everyday subjects – ended painting skyscrapers, Shirley Temple and young women sunbathing in Palm Springs on the eve of the second world war.

The thing about Lavery was that he started poor, very poor – and he never glamorised poverty. He was orphaned when he was three and spent his early years on his uncle’s farm in Northern Ireland, where the little Catholic boy learned to run from the Lambeg drums of the Protestant neighbours. He was then sent to Glasgow, where he was even poorer – he later said he took bread left for the pigeons. But there he took up the chance of art lessons offered by the philanthropic Haldane Academy for working men (the forerunner of the Glasgow School of Art). Although childhood poverty meant he was keen to earn what he could, he plainly also felt at ease with working people – see the sprightly ‘Phil the Fluter’ whom he painted in Kerry in 1924.

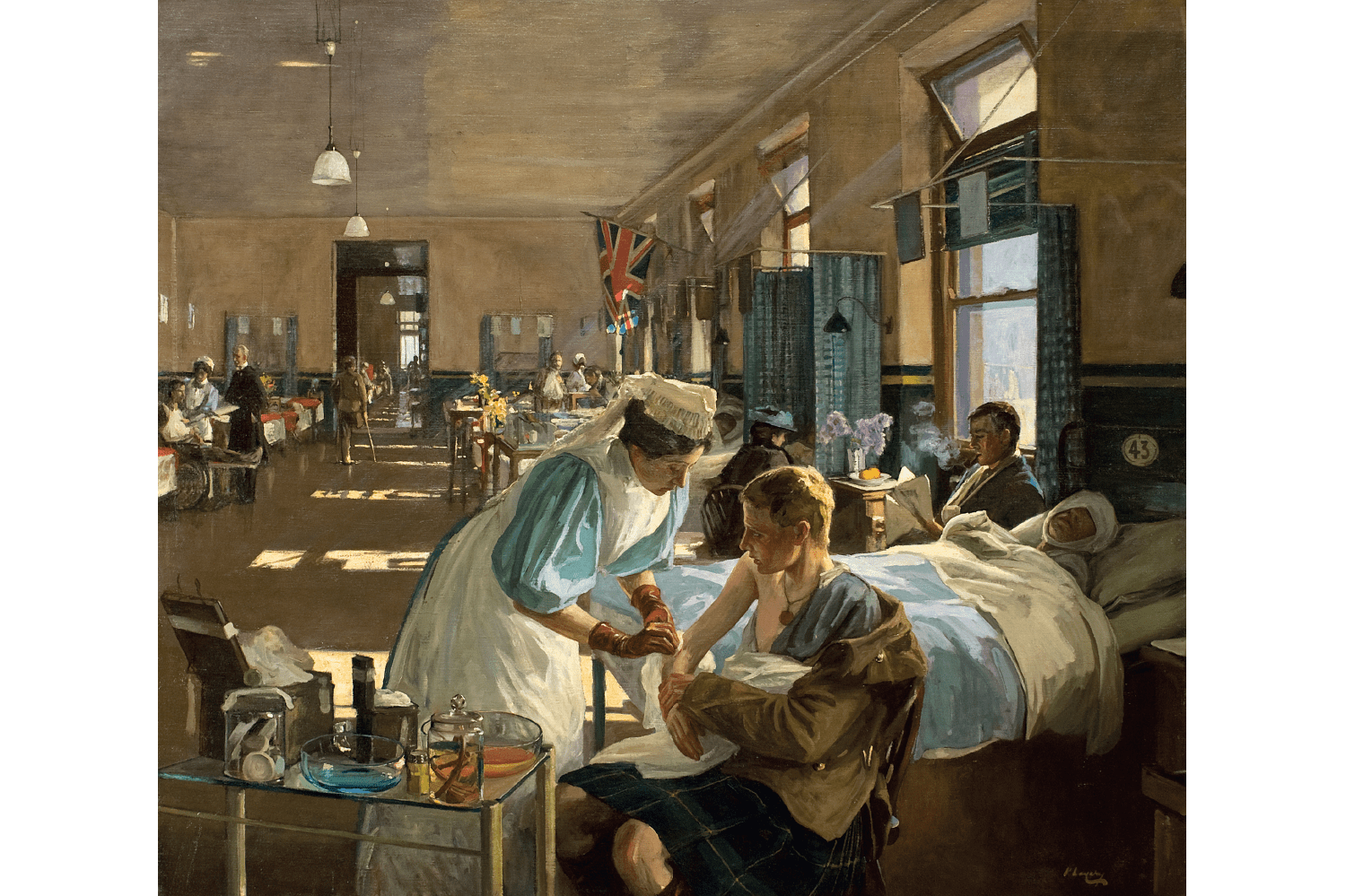

When you think of Lavery you think portraiture, often willowy women like his American wife, which is probably why he’s fallen off the radar; he paints in continuity with the past (he spent time copying Velazquez) and can’t be numbered among the moderns. But so what? He’s brilliant at capturing light and motion; his North African painting resembles the Spanish master of light, Joaquin Sorolla. In this show you see the sheer scope of his activity: landscapes, the Glasgow dockyards, war work – he was belatedly made a war artist towards the end of the Great War – mountain scenes (there’s a terrific vertical view of the Jungfrau), dancers in Tangiers, the aesthetic interiors of American millionaires.

He evolved over time, embracing modernity as he found it, but his first influence in France was formative. Bastien-Lepage, whom he met once, advised him to ‘select a person – watch him – then put down as much as you can remember. Never look twice… you will soon get complete action’. He had an astonishing ability to capture people in motion, and you see as much in ‘Played!!’ (see below), an 1885 picture of a young woman in straw hat and flounces returning a thundering serve on a tennis court.

Although the exhibition focuses on landscapes and people in places, there’s plenty for fans of the portraits, including a wonderful one with his only child, Eileen, his arm protectively around the back of her chair, while the pretty child gazes out, unperturbed. Close by is a painting of her mother, Lavery’s first wife, ‘An Irish Girl’ (1890), whom Lavery met when she was a London flower girl – the family claimed that this inspired Shaw’s Pygmalion. He married her thinking she was Irish and called Kathleen MacDermott and was taken aback after her death to discover that she was Welsh and called Annie Evans. Either way, her tubercular beauty was striking.

Comments