‘It had nothing to endow it with the title of studio at all,’ was Edward James’s first impression of Leonora Carrington’s Mexico City workspace in 1946. ‘The place was combined kitchen, nursery, bedroom, kennel and junk store. The disorder was apocalyptic: the appurtenances of the poorest. My hopes and expectations began to swell.’

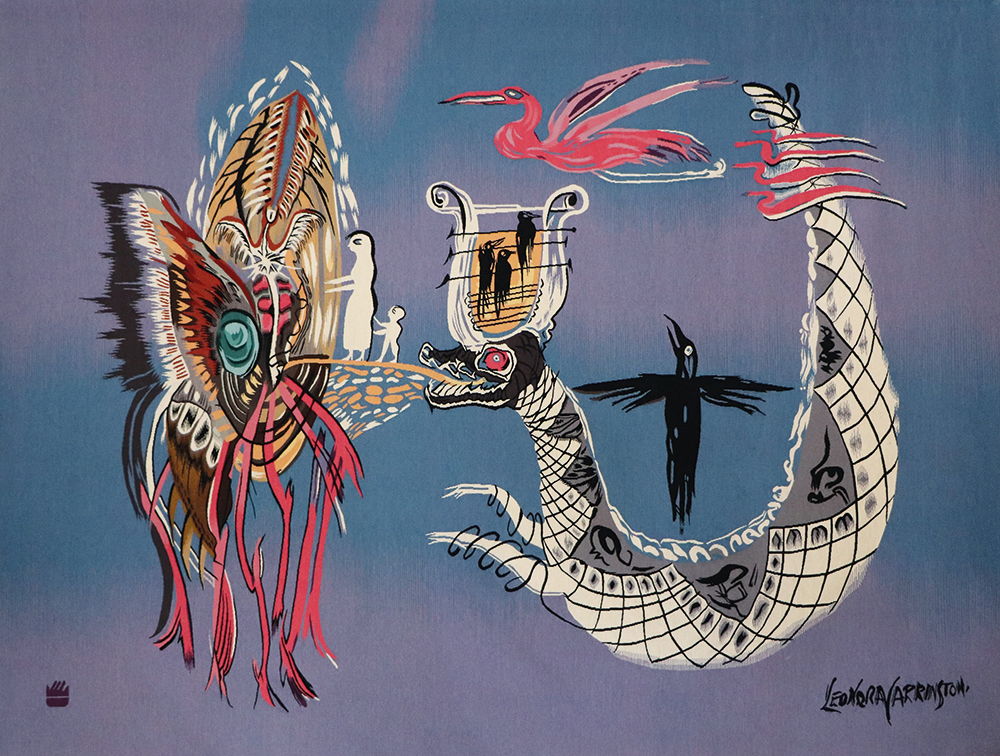

Carrington blended Egpytian, Mayan, Mesopotamian and Celtic legends learned at her nanny’s knee

Over six decades in the creative chaos of this house on Calle Chihuahua, Carrington would paint some of her best-known works and write her quirky serio-comic novella The Hearing Trumpet, which is narrated by a 92-year-old woman. If you want to understand Carrington’s art, read her stories: to get the full picture you need to hear that posh authorial voice, as insouciantly piquant as a hat pin – a tone instantly recognisable in the filmed interview with the nonagenarian artist that closes Newlands House Gallery’s current exhibition.

Most of the work in this show, curated by the artist’s cousin and biographer Joanna Moorhead, is late; there are some early drawings, including a delightful watercolour of a dragon and a princess painted in her teens, but many of the images are lithographic reproductions of earlier paintings made before the artist’s death in 2011. There are also tapestries (see below) woven to her designs in the 1950s, when she moved a family of Serape weavers into the house, and bronzes of figures featured in earlier paintings, cast with the help of assistants when she could no longer paint. Her paintings will be represented in a show at Firstsite, Colchester, next month; this exhibition provides an illustrated introduction to a fascinating life story, compellingly told by Moorhead.

The story follows the escape of the 20-year-old convent-educated, twice expelled aspiring artist from the ‘cattle market’ of the London season in 1937 into the arms of the twice married Max Ernst, her subsequent welcome in surrealist circles in Paris and her wartime retreat with Ernst to a farmhouse in Saint-Martin-d’Ardèche bought with money sent by her mother after her father disowned her. Photographs of the couple by Lee Miller show a carefree Carrington and a besotted Ernst, who clearly couldn’t believe his luck at landing this free-spirited English beauty half his age. She had come out, but not how her parents intended.

The rural idyll didn’t last. Following Ernst’s double internment, first by the French then the Gestapo, Carrington had a breakdown and fled to Spain, where she was subjected to shock treatments in a Santander asylum. She resisted the appeals of her Irish nanny, sent in a warship to bring her home, and escaped to Madrid, where she ran into a Paris acquaintance, the Mexican poet Renato Leduc, and married him on the promise of getting to Mexico. After hanging out in New York with the surrealists in exile – including Ernst and his new lover and future wife Peggy Guggenheim – the couple moved on to Mexico City where, amicably divorced from Leduc, Carrington married the Hungarian photographer Chiki Weisz and had two sons. For someone who was just getting noticed in New York, leaving for Mexico was not an obvious career move – but none of Carrington’s life choices were obvious. ‘Mummy told me I have such a bad temper that I’ll be an old witch before I am 20,’ she wrote at the end of the war in her autobiographical short story The Stone Door; in Mexico the escaped English debutante embraced that identity. Trios of wise old crones appear in ‘The Three Magdalenes’ (1988) and ‘Play Shadow’ (1977), while ‘Crow Soup’ (1997) could illustrate a recipe from the Weird Sisters’ cookbook.

A mythopoeic magpie, Carrington blended Egyptian, Mayan, Mesopotamian and Celtic legends learned at her nanny’s knee into a witches’ brew of an alternative universe dominated by women, animals and hybrids of the two. Apart from the appearance of her two young sons in ‘And Then We Saw the Daughter of the Minotaur’ (based on a 1953 painting), men don’t get a look-in. Her unselfconscious surrealism feels closer to Bosch, whose paintings she saw in Madrid, than to her male contemporaries: it comes completely naturally. In an image like ‘Nine, Nine, Nine’ (based on a 1948 painting), you sense her delight in the products of her own imagination: the topiary angel, the woman with the Struwwelpeter fright wig and the pet fox, the flight of reanimated pterodactyl fossils. Her hieratic sculptures of human-animal hybrids like ‘The Daughter of the Minotaur’ (2010) manage to be sinister and seductive at the same time, and you could believe her late series of bronze masks were capable of endowing the wearer with Jim Carrey-esque powers.

Commercial success, as so often with women artists, came late. She lived to see one of her paintings sold for more than $1 million; earlier this year ‘Les Distractions de Dagobert’ (1945) broke auction records for a female British artist when it sold at Sotheby’s in New York for $28.5 million. A biopic is said to be in the planning stages. What we need now is a big exhibition.

Comments