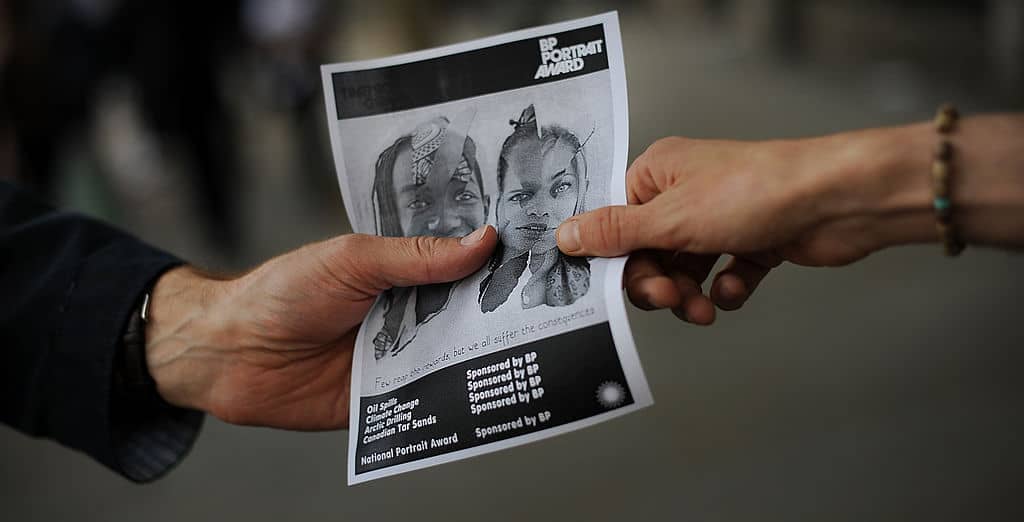

When is money so soiled that merely accepting it makes you tainted? It has been reported today that the National Portrait Gallery (NPG) and Scottish Ballet are ending their sponsorship deals with the oil and gas company BP following years of protests. Climate activists argue that these sponsorships launder the reputations of those responsible for despoiling the planet.

BP has long been a significant arts sponsor; the NPG’s annual portrait exhibition has been supported by the company since 1989. And in 2016 BP announced renewed sponsorship deals with the British Museum, NPG, the Royal Opera House and the Royal Shakespeare Company, pledging a total of £7.5 million over five years, starting in 2018.

At the time a climate activist campaigning against arts institutions – and indeed all museums – accepting funds from fossil fuel companies argued that ‘the new deals will not last five years’ because of increasing protests. Facing this pressure the RSC announced that it was ending its relationship with BP at the end of 2019 and now the NPG has followed suit. It seems unlikely that the deals with the British Museum and Royal Opera House will be renewed at the end of their current terms either.

Great art has been produced and preserved with tainted money

Fossil fuels are not the only substances that have contaminated donations in campaigners’ eyes. Tate Modern has been quietly removing the Sackler name from its walls. The Sacklers – whose UK charitable trust donated £14 million to British institutions in 2020 and over £60 million to British charities since 2010 – have paused their donations. The family’s wealth derived from Purdue Pharma, whose OxyContin painkiller has been blamed for contributing to America’s opioid epidemic. Campaigners in the US – such as the art photographer Nan Goldin – have staged theatrical stunts to protest the Sackler donations as climate activists have over here.

The campaigners can congratulate themselves on their successes – but these successes should be a cause for regret to the rest of us. Art institutions need funding. Surely what should matter is how the money is spent, not what the source of the funding is? Giving money to a public gallery is not like donating money to a political party. It may get you invited to good parties where you can rub shoulders with some shiny people; it may even contribute to you being rewarded with an OBE, CBE or a knighthood. But it does not buy influence.

Meanwhile, much good has come from funds accumulated from tainted sources. From the pyramids to Florence’s Medicis and our own seventeenth and eighteenth century slave traders to the ubiquitous philanthropy of America’s monopolistic moguls of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, great art has been produced and preserved with tainted money.

In what way does the source of these funds change what can be seen today? Clearly it is not the act of accepting the money that is wrong, but how it was initially acquired. And that acquisition will not be reversed by squeamishness on the part of our cultural institutions. Surely it is better that such funds are spent on a worthy cause rather than simply dissipated over generations of extravagant living?

Those who want to dictate who can legitimately give to the arts seem to believe that donating does great, indeed magical, things for the companies that donate. But does anyone really change their mind about climate change because they see the BP logo outside an exhibition?

Corporations are duping themselves if they believe these sponsorship deals really do their image much good. As the case of BP has shown, all it does create is a new platform for those opposed to a corporation’s activities. It raises awareness of the activists’ cause: more people will now be thinking about BP’s contribution to climate change, or otherwise, because of its arts sponsorships.

With the Sackler donations the case is even stronger. Until Purdue Pharma became well-known hardly any visitors to the galleries and museums they sponsored will have thought about the source of the Sacklers’ wealth. Indeed it remains of little concern to the vast majority of people. The Victoria and Albert Museum in South Kensington has a very prominent Sackler Courtyard as its Exhibition Road entrance. Nicholas Coleridge, the museum’s chairman, stated this month that ‘neither the director nor I have received any letters from any of the four million visitors to the V&A’ asking for it to be renamed.

Extractive industries will not be the last sector which are deemed to be too immoral to support worthy causes. But if art institutions are restricted further and further as to who they can get sponsorship from, art institutions will become more and more reliant on an already overstretched state instead. Rejecting donations from BP or the Sacklers will do nothing to alleviate climate change and will not free a single person of their opiate addiction – but it will make our cultural life more impoverished.

ENDS

Comments