Think of a Mexican painting, and chances are you’ll conjure up an image of an eyebrow-knitted Frida Kahlo, or a riot of exotic figures by her husband Diego Rivera, or a brightly coloured guitarist by Rufino Tamayo. What you’re unlikely to have in mind is an earthy landscape with a dusty road leading to a nascent city, dotted with hyper-real plant life, and an eagle soaring under a vast, cloudy sky.

This is ‘The Valley of Mexico from the Hill of Santa Isabel’ (1877), the finest work by a painter who was a household name in Mexico long before Kahlo, Rivera or Tamayo. And from next week, it and many others of his works will hang in London’s National Gallery, the first historical Latin American artist ever to have been exhibited there. His name was Jose Maria Velasco (1840-1912); and though he was fêted in his native country, in his lifetime and beyond, he has long been forgotten in the wider canon of art history. So it’s at first glance curious, and on further inspection intriguing, that the National Gallery is bringing 30 of his paintings and drawings from Mexico to London. The last time they left the country was for an exhibition in Texas in 1976; and though Velasco’s revered in Mexico, where a whole section of the Museo Nacional de Arte in the capital is devoted to him, there’s no work by him in any UK collection and hardly any work in European galleries.

One reason proffered for the London show is that 2025 marks the 200th anniversary of diplomatic relations between the UK and Mexico, but that seems a bit thin. More convincing is the idea that Latin American artists such as Velasco were left out of the canon because they were in the wrong place at the wrong time: if he had been born in France, or Germany, or England, his story might have been very different. Instead, Velasco’s work has languished, uncategorised and (outside Mexico at least) widely unknown. Even given the National Gallery’s remit to bring non-European painters to wider acclaim (Winslow Homer in 2022 and the Australian impressionists in 2016), Velasco is left-field.

The proposal from the show’s curators, though, is that he is an artist for now, with as much to say nearly two centuries after his birth as in his lifetime. His genius, say co-curators Daniel Sobrino Ralston and Dexter Dalwood, lies in the way he telescoped Mexico’s magnificent and convoluted history – its pre-Hispanic past, its colonial era, the creeping arrival of industrialisation of his own time – on to his canvases, representing an attempt to link past and present, and through that to hint at what the future might hold.

His aforementioned ‘The Valley of Mexico from the Hill of Santa Isabel’ is the quintessential work in this respect. In the distance the buildings of the expanding capital city are already beginning to spill across the plain of the valley. In the centre ground, the Basilica of the Virgin of Guadalupe – built to mark the Virgin Mary’s 1531 supposed appearances to a Nahua peasant – represents both Spanish colonial rule and the intermingling of Mesoamerican and Catholic tradition. And via a road that snakes across the hillside to the foreground – closest to the viewer but in time the most distant of all – there is a cactus and an in-flight eagle with a bird in its beak. These emblems link to the myth around the foundation of Tenochtitlan, the forerunner of Mexico City. According to one ancient story, an eagle with a bird (or snake) in its beak would alight on a cactus to signal where the city would be built.

Velasco was left out of the canon because he was in the wrong place at the wrong time

What’s most striking about the painting is how overawed the forces of man are by the forces of nature. The church is but a few specks of paint. It wasn’t only the history of human civilisation that Velasco sought to chronicle in his work: it was the history of creation, too. ‘Geology was a new science in his day,’ says Dalwood. ‘People were realising that the Earth was much older than had been previously thought. So geology took on a new excitement and like Cézanne, Velasco became obsessed with geology, and how its story was evolving.’

‘Rocks’ (1894) shows a half-shaded outcrop, under an ominous sky, on the hill of Tepeyac, to which he had moved the previous decade. It was close to the village (and shrine) of Guadalupe, and he would paint both the rocks, and the wider view of the valley in which it was situated, many times. The subject matter is similar to Cézanne’s rock and quarry paintings, but the technique is different. Where Cézanne is broad-brush, approximate, governed by the paint, Velasco is precise, life-like, and exacting in his desire to represent the scene precisely as he sees it.

He had been born into a humble family outside Mexico City, moving there as a child; he always knew he wanted to paint, and he combined his first job selling shawls in his uncle’s shop with evening classes in drawing. He progressed to a place at the prestigious Academy of San Carlos and studied under the Italian landscape painter Eugenio Landesio, who encouraged his students to draw from life, in plein air.

But whereas Landesio favoured a warm, romantic lens, Velasco took a harder view of the world, juxtaposing nature with encroaching industrialisation. His two depictions of ‘The Goatherd of San Angel’ (1861 and 1863), painted while he was still a student, signalled his independence from his teacher: alongside the goatherd and his charges, and to the right of leafy green trees, is a factory, one of Mexico’s first textile mills (related perhaps to the family business with which he was at this stage involved), its chimney belching thick, black fumes into the powder-blue sky. In the 1863 representation of the scene, the foreground features a remarkably precise agave plant, as well as a native Mexican plant known as anoceloxochitl, with an orange and black flower. This and many other detailed depictions of plants and trees display another feature of his oeuvre, which is the fact that as well as art and geology, he studied botany, palaeontology and zoology. His polymathic fascination with the natural world included the discovery of a new kind of salamander in Santa Isabel Lake – it is named after him: Ambystoma velasci.

Velasco is an artist with as much to say nearly two centuries after his birth as in his lifetime

Velasco’s works will certainly boost the current Mexican offering at the National Gallery; its own collection boasts just one work referencing this vast country and its history, which is Manet’s ‘Execution of Maximilian’ (1876-8). Velasco is thought to have himself painted a portrait of this ill-fated Austrian emperor, puppet of Napoleon III, though that work is lost. European outrage at Maximilian’s demise meant Mexico was excluded from many events in the years following his execution. Velasco’s 1877 ‘The Valley of Mexico’ (there are several others of the same scene, painted in different years) was destined for the Parisian Universal Exposition of the following year, but political fallout meant Mexico wasn’t invited to attend, and Velasco sent the work at his own expense, to be exhibited in the Spanish pavilion.

It wasn’t until he was 50, in 1889, that Velasco left Mexico for the first time, travelling to Paris where he saw work by the impressionists. On his return, he wrote that, while he admired the meticulous drawing and fine finish of some French artists, others were more about ‘spreading paint with a spatula and large brushes, sculpting more than painting, disregarding form, correct proportions, and modelling’. Dalwood says he certainly didn’t reinvent his painting as a result of his Parisienne adventure: ‘He stuck with the idea of his role as an artist who could present the complexities of a layered world.’

The Mexico to which he returned was now ruled by Porfirio Diaz, and Velasco’s supposed links to the dictator – his works were sometimes given by Diaz’s regime to visiting dignitaries – would for ever count against him. Sobrino Ralston, however, thinks ‘the link is hard to pin down…We take the view that there was some association, but we know little of Velasco’s politics – though I’m sure he was conservative in some ways. He certainly wasn’t painting on the orders of Diaz.’

Although he had eschewed impressionism, some of his final works – small paintings on postcards – display a looser brush and a lighter palette reminiscent of the movement. The most poignant piece in the show is ‘Study of Clouds’ (1912): it shows a hazy, free-flowing sky with an amber plain in front. Perhaps he had been intending to put some trees, or a lake, or a carefully drawn plant there, but having worked on it in the morning, he died later the sameAugust day.

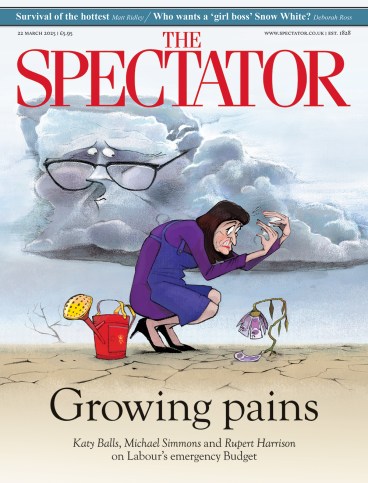

It’s to the National Gallery’s great credit that it’s chosen to focus on an unknown, whose work was all about the tangled networks of history. Certainly the decades after his death confirmed his decision to home in on encroaching industrialisation: the valley of Mexico he painted is now unrecognisable, a sea of concrete, roads, buildings, its lakes drained, home to the fifth biggest city on earth. So there’s an irony in the gallery’s choice of lead image: a majestic cactus, modern in form, deep green in colour. It’s brazen in its simplicity, a foil to Velasco’s true work: but it’s clearly designed to entice an Instagram-fixated public into a quietly complex show; a show that will reap rewards for those willing to linger over its profound messages.

Jose Maria Velasco: A View of Mexico is at the National Gallery from 29 March to 17 August.

Comments