It’s easy to forget what a mess of an art form opera once was. For its first 100 years it had no name, it had no fixed address, it didn’t really know who it was or what it was doing. You’d find it at schools, at weddings, at political functions. It was an artistic whore for hire. Embroiled in an epic tug-of-war as to which of the three art forms — word, music or dance — should be primary, it was also lithe and experimental. In fact, it was more like performance art than anything you’ll witness in a modern opera house.

Why this historical detour? To remind us not to despair over the possible demise of the English National Opera (which has lost two of the more capable members of its senior team in the past week and whose receipts have taken a nosedive). Opera is a durable beast. It doesn’t need opera houses. It doesn’t need opera companies. It doesn’t even need subsidies to survive. Some of its most heroic moments have been in the leanest years. Think of the flourishing of Purcell at the art form’s dawn or the arrival of Britten’s Peter Grimes a few weeks after the end of the second world war. At neither point did this country have a single fully functioning (let alone subsidised) opera house.

Besides, aren’t we supposed to love challenging establishment institutions in the arts? We should. All the great turning points in opera were ushered in by economically independent enterprises swooping in on the carcasses of sclerotic creative cartels. Without a visit from an entrepreneurial troupe of Italians to Paris in the 1750s, the comic revolution that swept aside a French state monopoly on what opera should look like (and paved the way for Gluck, Mozart and Rossini) might never have happened. Without Philip Glass’s risky commercial punt on his five-hour Einstein on the Beach (1976) — which saw the composer personally take on debts that he only paid off when he was in his 40s — post-war opera would be missing its greatest work.

This American masterpiece, by the way, when it finally received its UK première in 2012, was turned down by the ENO. I’m reliably told that the ENO knew the unionised chorus and orchestra wouldn’t give way to the specialist Philip Glass Ensemble, if it meant that the ENO orchestra and chorus would go unpaid for the duration of the residency. The production was instead snapped up by the Barbican Theatre — and sold out. Says it all really.

To an extent I feel for the ENO. It is hamstrung. Set up on 19th-century principles, the ENO is incapable of doing justice to contemporary opera, so much of which rejects the bread-and-butter set-up — chorus, proscenium arch, song.

Of the dozen or so new (or newish) operas I’ve seen over the past few months only one — Glass’s tidy, forgettable The Trial (2014) — was produced by an opera company. The most exciting, Salvatore Sciarrino’s Lohengrin (1982) and Simon Steen-Andersen’s Buenos Aires (2014), both received their UK staged premières courtesy of itinerant music ensembles performing at the ever-excellent Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival.

Opera-house set-ups would have been silly for both. Not just because of the delicacy of their scores — Sciarrino’s is made up of the wispiest tendrils of sound — but because neither contains any real singing. (There is a precedent for this: the 18th-century German Melodram, a popular operatic sub-genre, substituted singing for speech.) Steen-Andersen’s ingenious investigation of why an art form as hemmed in and as ostensibly absurd as opera still has the power to move delivers two memorable climaxes: a reconstruction of a Rossini quartet sung through electronic voice boxes and a love duet for two golf balls played out on a remote-controlled mixer.

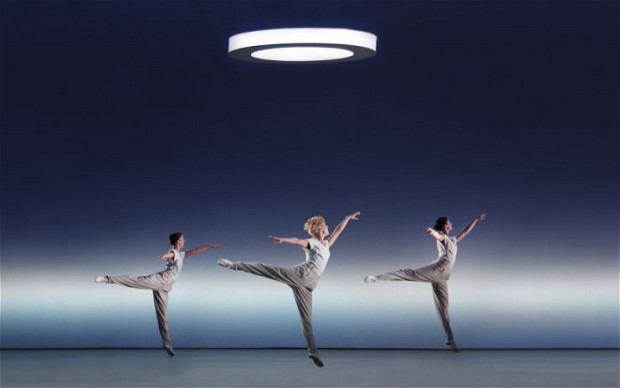

But why not angle our lenses even wider. If early opera was performance art, might not performance art be opera? Consider opera as Gesamtkunstwerk — as an act of accounting how we see, as well as how we hear and how we think — and the art gallery is about the only place where opera is really taking place today. Witness the shape-shifting work of Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster or Jimmy Merris and you will see the true inheritors of early operatic experimentalism. They talk a lot about opera in the art world. If only the opera world would listen.

That said, there is one firm believer in the operatic tradition of the 19th century, who 20 years ago wrote a masterpiece for it. And that’s James MacMillan, whose gothic tragedy Ines de Castro (1996) just finished its run at the Scottish Opera. But MacMillan is the exception that proves the rule. Very few others have faith in the past like MacMillan. And even fewer have the ability to meld tradition with modernity. Complex percussive landscapes — a bewitching wash of flexatones and thundersheets, mark trees and tom-toms — sit side by side with thuggish brass fanfares and counterpointed chant.

So let’s wave goodbye to the ENO. Redistribute its millions, Arts Council, and you will see an encumbered art form bloom.

Comments