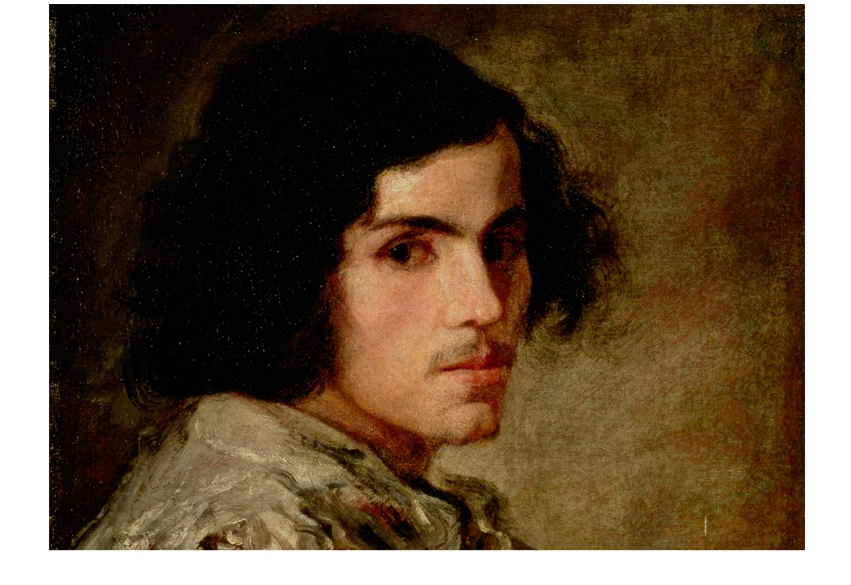

Not content with being the greatest sculptor of his age and one of its most gifted architects, Gian Lorenzo Bernini had some talent as a painter and draftsman. Surviving self-portraits reveal him as the possessor of a positively overstated physique du role. In its most youthful incarnation the face has an air of presumption and entitlement which adulthood will darken with a combativeness that is almost wolfish. Even in the chalk drawing made around his 80th birthday (now in the Royal Collection at Windsor) the glance, under bushy white eyebrows, still smoulders and the slightly parted lips seem poised to challenge or command.

Born in Naples in 1598, Bernini spent almost the whole of his working life in Rome, a city whose profile he memorably refashioned and to whose rulers he became indispensable as an image-maker. The subtitle of Franco Mormando’s vigorous, keenly researched biography is instructive. The Rome most of us go to see belongs as much to this stubborn, tyrannical wizard of the Baroque as to the Caesars, the late-Antique mosaicists or Michelangelo on his Sistine scaffolding. Those sweeping colonnades outside St Peter’s, the sumptuous baldacchino above its altar and Piazza Navona’s obelisks and fountains are inspirations whose ideal synthesis of nobility and exuberance has set a benchmark for urban spaces ever since. ‘If you scratch the surface almost anywhere in Baroque Europe,’ observes Mormando, ‘more often than you expect you are likely to find Bernini in some shape or form.’

Sculpture rather than architecture clinched his early reputation among the Roman cardinals and their cohort of fixers, pensioners and hitmen. The Vatican hierarchy throughout the 17th century was conspicuous for its greed and extravagance. None of the seven popes who patronised Bernini cultivated much in the way of spirituality. Laying up treasure in heaven, for pontiffs such as Urban VIII and Innocent X, seemed altogether less important than nest-feathering for their numerous family dependents and bolstering the papacy’s dwindling prestige among the great powers of an increasingly secularised Europe.

The drama and intensity of Bernini’s religious images was almost better than these princes of the church deserved. His theatricality — he was a playwright and stage designer in his spare time — shapes a specific context for several of his greatest sculptures, one in which fresco, stucco decoration and carefully manipulated natural lighting each contribute to the performance. In the Cornaro chapel Teresa of Avila undergoes her mystical ‘transverberation’, from the dart of a smiling angel, in the presence of marble spectators watching the show out of side boxes. Similar scenic effects enthral the viewer at San Francesco a Ripa, where the Blessed Leonora Albertoni’s convulsive ecstasy sends shockwaves rippling through the folds of her nun’s habit.

An outstanding recent exhibition in Florence focused on the positively uncanny magnetism of Bernini’s portrait busts. Mormando’s biography underlines their significance as status indicators for everyone from Francesco d’Este, Duke of Modena, who paid the sculptor ‘a whopping 3,000 scudi’ for hiding his not altogether princely features under heroic drapery and cascading coiffure, to Cardinal Richelieu, whose countenance, lantern-jawed and basilisk-eyed, ‘makes some of us just shiver to be in its presence’.

Works like these secured an invitation to Paris from Louis XIV. Bernini’s French sojourn makes for melancholy reading. Crowds initially lined the streets and squares in towns along his route northwards. ‘This is a completely extraordinary honour,’ harrumphed a French archbishop, ‘one that the city reserves only for princes of the blood.’ To the sculptor himself it seemed ‘as if an elephant were travelling around’. His evident contempt for Louis’s court artists rapidly antagonised both the monarch and his chief minister, the reptilian Jean-Baptiste Colbert, who not unreasonably disparaged Bernini’s planned extension to the Louvre for its failure to deal adequately with the simple matter of where to put the privies. A long-delayed project for a royal equestrian statue resulted in a dog’s dinner. The oddly fish-faced horse seems more of a spavined nag than a plausible Pegasus for the Sun King. Louis had it dumped behind a hedge at Versailles.

Should we have cared to sit down to dinner with the illustrious cavaliere, as the sculptor-architect eventually became? Though obviously not indispensible, this litmus test of biography is worth applying. At home in Via della Mercede, off Piazza di Spagna, there was a Signora Bernini, Caterina Tezio, whom he agreed, on their marriage in 1639, ‘to treat exquisitely if she will prove capable of tolerating his nature, which is neither easy nor ordinary’. Something more than the invincible allure of a celebrity husband permitted the marriage to last for 34 years and Bernini shed bitter tears on receiving the news, while in Paris, of Caterina’s death.

That he remained ‘neither easy nor ordinary’ became part of his mystique. Successive popes found his tantrums and crotchets more entertaining than irksome. Short-lived Fabio Chigi, as Alexander VII, proved the most sympathetic of them, a martyr to gallstones but suffering also, according to his detractors, from mal di pietra, ‘building sickness’, which only a sustained collaboration with Bernini could alleviate.

Another kindred spirit was Alexander’s most illustrious Catholic convert, Queen Christina of Sweden. On his deathbed Bernini begged for her prayers because

he believed the great lady had a special language with which to make herself understood by the Lord God, just as in turn with her God made use of a language that only she was capable of understanding.

From several aspects there is something heroic about the life Franco Mormando so expertly chronicles here. Admittedly Bernini died full of years, loaded with honours and a multi-millionaire, but his successes seem the more richly deserved in the almost hysterically volatile context of the times in which he lived. Cunning, vain and an outright bully he may have been; and unscrupulous in turning others’ talents to his own advantage. (Giuliano Finelli, the Tuscan sculptor who fashioned the more delicate portions of the groundbreaking ‘Apollo and Daphne’ group in 1625, left Bernini’s studio in anger and disgust at a general failure to acknowledge his contribution to the statue’s impact.)

Yet this arrogant master of marble was also a survivor. To carve out a career like his in 17th-century Rome, with its casual violence and obstinate sinfulness, a place of murders and plagues, sodomite monsignors and brawling nuns, was a notable achievement enough, but his imaginative and spiritual legacy to his adoptive city transformed the values of those who lived there and continues to lift the heart.

‘Universal was the mourning in Rome for the loss of this man,’ declared his son Domenico, ‘well aware that she had been further endowed with great majesty by means of his untiring labours.’ Quite so.

Comments