Sir Roger Casement never deserved to hang

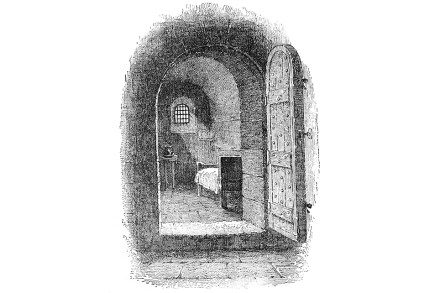

Telling the story of Sir Roger Casement’s life is a challenge for any biographer. In the land of his birth, he is remembered as a national hero. His remains lie in the Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin beside the graves of Daniel O’Connell and Charles Stewart Parnell. He is there because he was hanged in Pentonville Prison in August 1916 as one of the leaders of the Easter Rising. The awkward fact that Casement had become opposed to the Rising and had tried to prevent it does not fit either the heroic Irish narrative of his life or the official English account of the wartime traitor who died on the gallows.