Among the spoils of a lockdown clear-out was a box of my grandmother’s books: Woolf, Austen, Mitford and The Complete Nonsense of Edward Lear with a jacket by Barnett Freedman. You only need to see a corner of the cover — a stippled trompe-l’oeil scroll — to recognise the artist. Freedman, a Stepney Cockney born to Jewish-Russian parents in 1901, delighted in paper games. Maps unfurl, book leaves fly, cut-outs and cartouches abound. His designs are a miscellany of silhouettes, decoupage, concertinas, peek-a-boos, lift-the-flaps and grubby thumbprints. Edges are ragged, endpapers torn. On the dust jacket to Siegfried Sassoon’s Memoirs of an Infantry Officer (1931), a military map has been imperfectly pasted over the back cover as if slapped up on a post alongside marching orders. Whatever glue Freedman uses, it always seems to be peeling.

This is a wholly lovely exhibition. I was cheered by Freedman’s jesting and left tearful by his wartime portraits. Freedman was among the ‘outbreak of talent’ generation identified by the Royal College of Art tutor Paul Nash: Edward Bawden, Eric Ravilious, Enid Marx, Edward Burra and Freedman. His RCA paintings are not altogether successful: lumpen figures, clotted landscapes. In 1924, Freedman secretly married his fellow student Claudia Guercio, daughter of a Sicilian fruit exporter, and after graduating the following year the couple took two rooms near the Euston Road. Looking back on those years, Freedman remembered: ‘I nearly starved.’

Looking at Freedman reinforces my feeling that the messaging of the present crisis is visually dismal

Work picked up in 1927, when Freedman was commissioned to illustrate Laurence Binyon’s poem ‘The Wonder Night’, part of Faber & Gwyer’s (later Faber & Faber) series of Ariel Poems — decorated chapbooks intended ‘to take the place of Christmas cards and other similar tokens’. Freedman and Faber were a happy match. While working on Sassoon’s Memoirs, Freedman spent three weeks learning the art of lithography — a process of chemical printing in which the artist draws with a greasy crayon on stone. The printing depends on the difference between greasy and non-greasy surfaces that either ‘take’ or reject ink. Freedman became a lithographic magician, conjuring nocturnes and hazy harvest afternoons and subtle effects of snow, mist and smoke. In an edition of Oliver Twist (1939) for the Heritage Press, Bill Sikes appears haloed in uncanny purple, lurid as a bruise, while the Artful Dodger is positively filthy with ink. Freedman had a knack for uncanny angles: the bull’s-eye view of a darts champion, a laid table looming obliquely in a vignette from Anna Karenina (1951), a packing-case perspective of a Moscow townhouse in an illustration for War and Peace (1937–8).

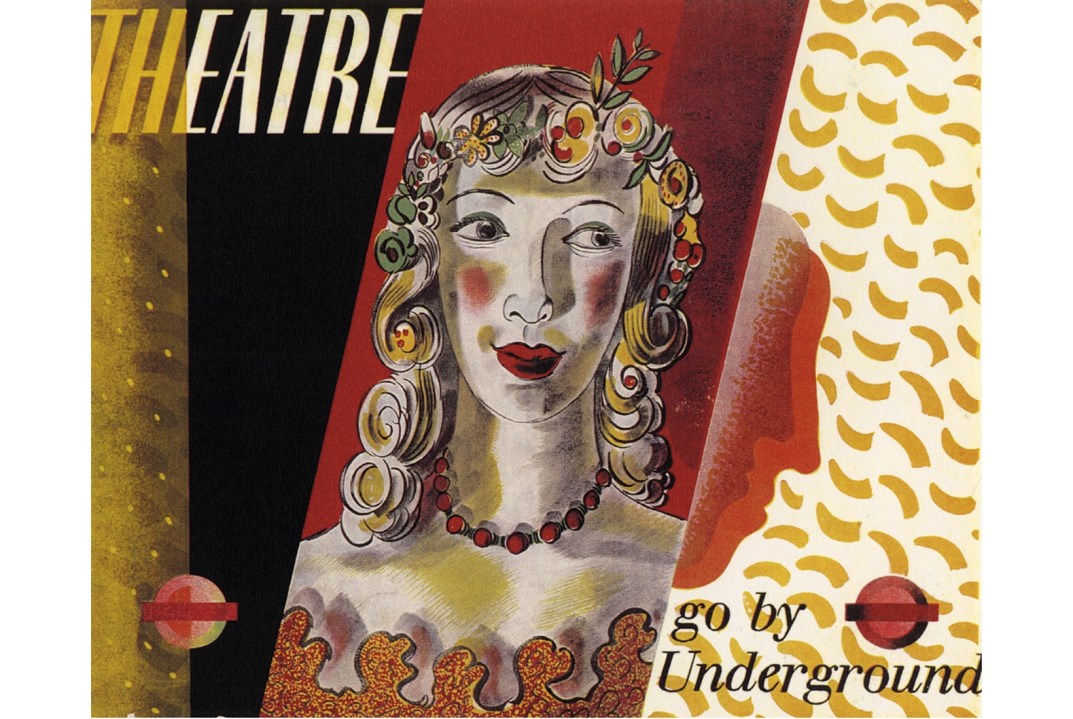

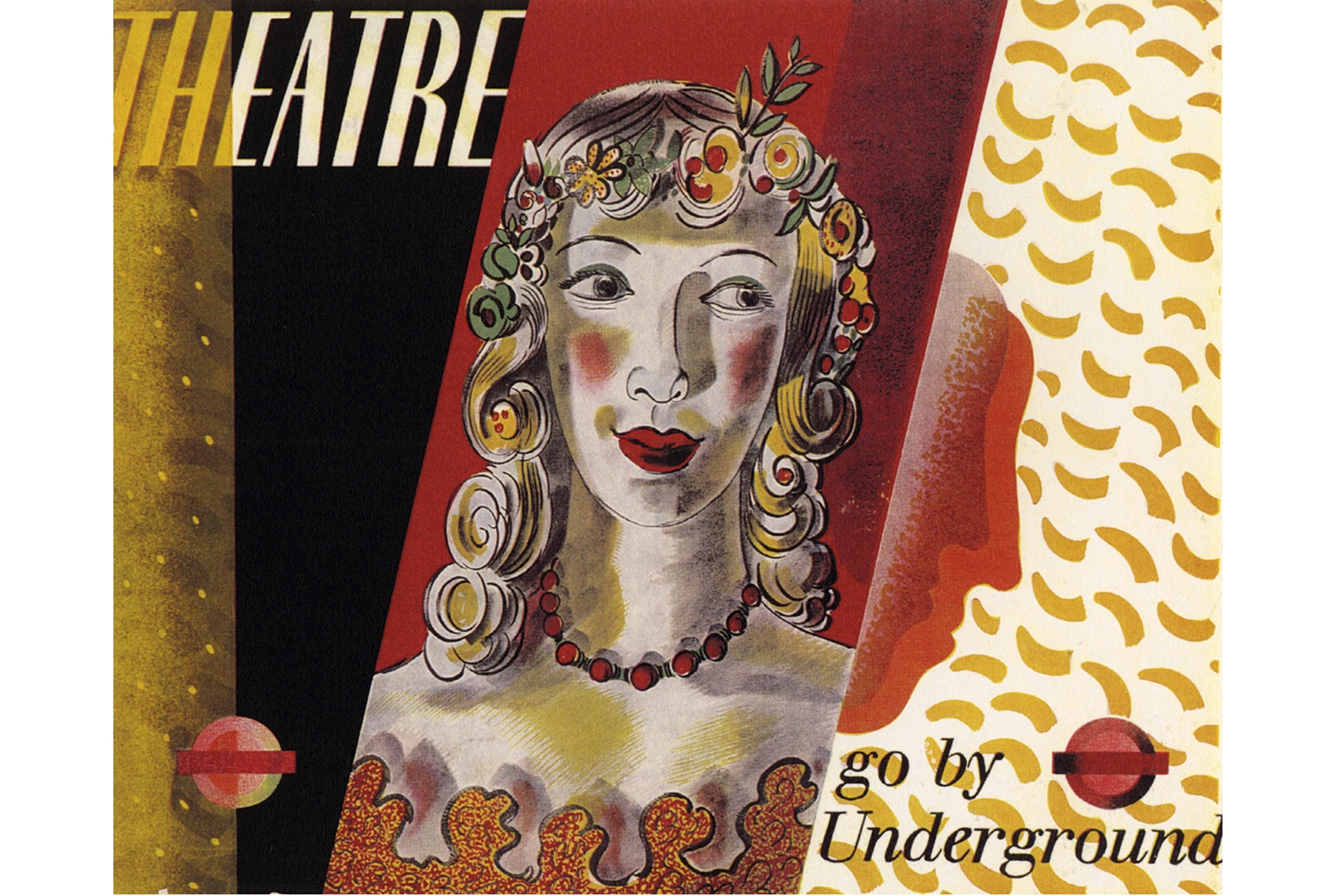

Freedman made no distinction between fine art and commercial art, only ‘good art or bad art’. His commercial work — from stamps to commemorate the Silver Jubilee of King George V to book tokens with tear-off ‘Ex Libris’ plates, from Shell and London Underground posters to bright and bonny bunting for the Queen’s Coronation — is very good indeed. His posters are direct and diverting, clear and eccentric. Looking at Freedman only reinforces my feeling that the messaging of the present crisis has been visually dismal. ‘Stay Home, Protect The NHS, Save Lives’ in hazmat yellow and red, ‘Stay Alert, Control The Virus, Save Lives’ in emetic yellow and green. Speed was of the essence — no time for lettering competitions back in March — but if we are going to go on with the farrago of face masks, hand-sanitising stations and umpteen hundred admonitory signs, cannot Transport for London, Network Rail and the government endeavour to find the Barnett Freedmans, Abram Gameses and Edward McKnight Kauffers of our age?

During the war, Freedman was recruited to Kenneth Clark’s Official War Artists scheme. His ‘Interior of a Submarine’ (1943) is close and stagnant, almost intestinal, all wheels and pipes and sepulchral light. Freedman’s ‘Coast Defence Battery: September 1940’ makes camouflage netting into something gorgeous and soaring. Clark hung the painting in the National Gallery where he said it made its neighbours look ‘very flimsy’. The works that had me blinking back tears were the pocket portraits of ships’ crews and the personnel of aircraft factories. There they all are: from generals to buglers, technicians in lab coats to ladies in floral aprons, each devotedly observed. When HMS Repulse was sunk by the Japanese off the coast of Malaya on 10 December 1941, Freedman received a letter from Janet Newbery, widow of crew member Douglas Newbery. ‘You can imagine now what it would mean to me,’ she wrote, ‘to have a copy or even a photograph of this portrait. I have one good snapshot taken on board by Lt. Hunting & that is really all that I possess in the way of a good likeness of Douglas.’

Freedman himself died regrettably young in 1958. This is a rare exhibition that left me in the last room holding out my bowl like Oliver Twist and begging: ‘More!’

Comments