‘I’ve been seeing the bare bones of London,’ explains the landscape artist Peter Brown, who is known affectionately as ‘Pete the Street’. We meet on the corner of St Martin’s Lane, where he is painting the view facing north, taking in the Coliseum, the Duke of York theatre and an Iranian restaurant called Nutshell. ‘The pandemic has been a good opportunity to paint all these West End theatre awnings.’

What has he noticed about London during the pandemic? ‘UPS vans, everywhere,’ he says. How about Deliveroo bikes? ‘I’ve spotted less of those.’ Has London changed over the past year? ‘I met a bloke on Old Compton Street who described how it feels really well to me,’ Brown says. ‘He used to work as a performer and spent a lot of time touring theatres in English seaside towns. Back in their day those theatres were grand and impressive, but they had become neglected and rundown. He said London now reminded him of the faded glory of Blackpool.’

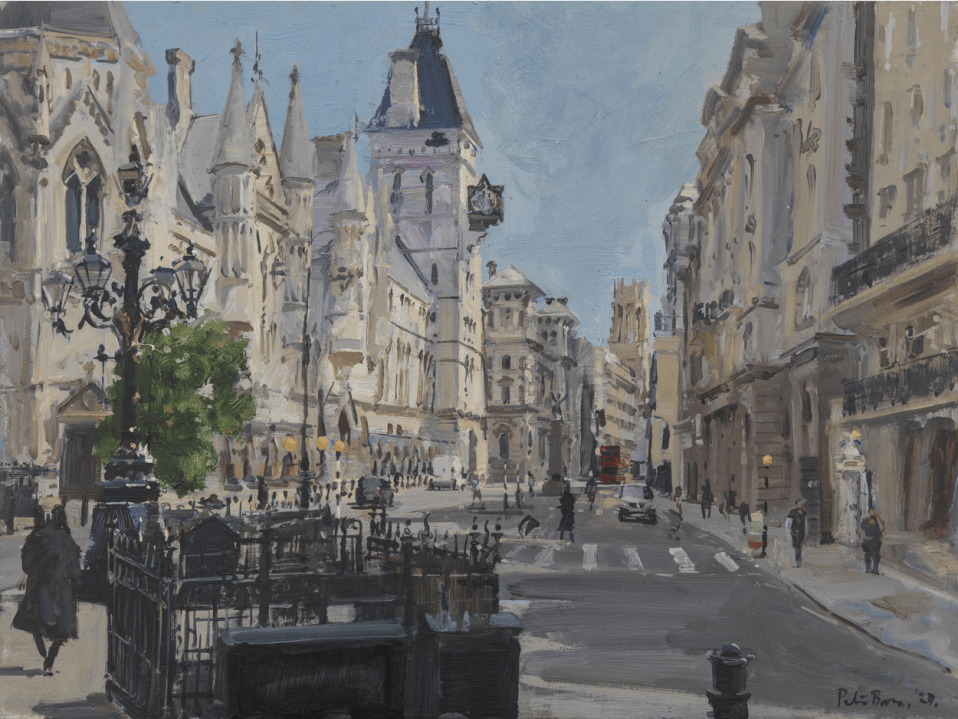

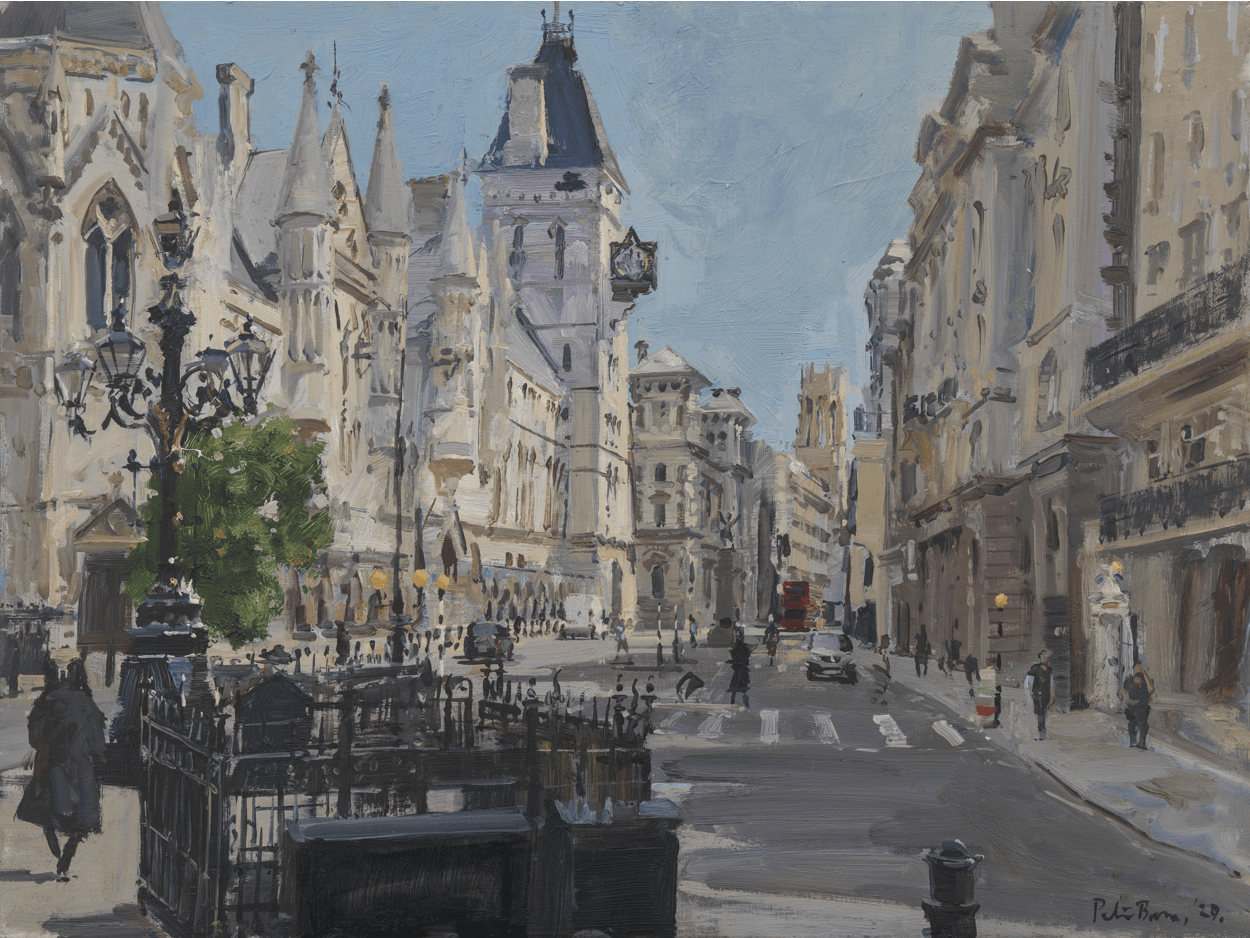

The city may be looking a little forlorn but has it not been an opportune moment to paint the capital, with the streets cleared of the usual crowds? ‘Well, it was great seeing the actual architecture and it was interesting on a technical level seeing the lie of the land, say between Fleet Street and Ludgate Hill. Ultimately, though, it was really depressing.’

London reminded him of the faded glory of Blackpool

In the first lockdown, Brown decided that he couldn’t really claim his work was ‘essential’ so instead he retreated indoors, along with the rest of the country. He lives in Bath and spent most of last spring painting his family as they readjusted to their new life, staring at their phones, baking in the kitchen, doing the washing-up. In one of his paintings, there is a bottle of Ribena and a tube of Heinz ketchup on the kitchen table. It feels familiar.

But still life — or at least slow life — isn’t his normal subject matter. He prefers painting outdoors, because you have ‘less control’. His pictures often feature blurred crowds. As the first lockdown started to ease, he focused on Bath’s outdoor spaces. ‘I was really interested in painting the relaxing of lockdown. I wanted to find people again.’ His pictures from the Royal Crescent show groups spread out evenly across the grass, adhering to social distancing guidelines. ‘Some people were spread out, some weren’t. It was a really weird time.’ In years to come, I wonder whether someone looking at these paintings will even be able to tell what is going on. The scene doesn’t look particularly out of the ordinary.

Brown travelled around the country as much as he could. He spent time in Bristol — ‘London with camper vans’ — and Harrogate. ‘You know when the papers were going on about these “awful people” going down to Bournemouth? Well, I went down to Bournemouth. I just did what everyone else did. But you get there and then realise, oh no, I’m a crowd! I painted it and there were masses of people on the beach, although it wasn’t as crowded as the photographers made it look.’

When the second lockdown arrived, he ‘painted through it’. ‘I came back to London. I painted New Bond Street. All the lights were on in the shops and the security guards were outside but it was all very quiet.’ His paintings tend not to feature individual, identifiable figures but the pandemic has, he says, revealed some of the sadder aspects of London life that are concealed by all the commotion. ‘Lockdown has exposed what is there normally in London: people with chronic mental health issues, people who are homeless, people who are really sad. You hear and see them more when everyone else is gone. A crowd can be a lonely place.’

But Brown is the first to admit that his art is neither revolutionary nor political. ‘I’m really bad at conveying a message. I don’t have an agenda at all. When something like Black Lives Matter happens, I don’t feel qualified to make any decent comment on it. That’s a problem I have but I am just interested in the everyday, the mundane. I’m not doing anything other than recording ordinary life. I suppose there is some use in that as a record.’

Despite his modesty, Brown holds the distinguished post of being president of the New English Art Club, which was founded in 1885 as an alternative venue to the Royal Academy. His own influences are what one might call classic English: Turner, Constable, Sickert (who was one of the founding members of the NEAC). Brown is particularly fond of paintings of London from the 1950s. ‘What I love about them is the sense of time past.’ He tells me about an artist called Christopher Chamberlain, who studied at the Royal College of Art and taught at Camberwell School. ‘He never really exhibited. He was just into painting local scenes. Normality painted beautifully.’

The past year has been anything but normal. Will Brown miss anything about his time recording it? ‘At the moment, as with all moments in time, when you are trying to capture it, you want it to freeze. So I want to make sure that I capture as much of this as I can while it’s here. But I’m looking forward to this city coming back although I suspect it is going to happen slowly.’

As the crowds start to return to London, it will become harder to spot Brown. I first came across him earlier this year when I noticed his easel propped up outside the Pret in Trafalgar Square while he bought a coffee. I asked whether his current painting was for sale. It was, but was somewhat out of my price range. His pictures tend to go for thousands.

In busier times, I probably wouldn’t have noticed him. I get the impression he prefers it that way.

Comments