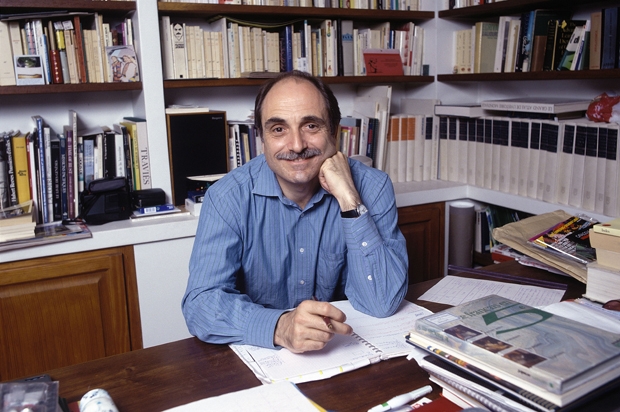

Paul Fournel is a novelist, former publisher and French cultural attaché in London, and the provisionally definitive secretary and president of the select literary collective known as Oulipo, whose fellows have included Raymond Queneau, Georges Perec and Italo Calvino. Members of Oulipo remain members after their deaths. In this respect, it is the French literary equivalent of the Hotel California, a comparison I suspect its followers would neither welcome nor necessarily understand. But playful and defiant obscurantism is all part of Oulipo’s raison d’être.

Dear Reader is set in the world of publishing and tells the tale of a middle-aged editor, Robert Dubois, struggling to adapt to the rise of the e-book; the surname is no accident. The book is brief, witty, intellectual and wonderfully quotable.

It also adheres faithfully to the Oulipian doctrine of ‘creative constraint’. The most celebrated example of this is Perec’s La Disparition (1969), composed entirely without using the letter e and heroically translated into English by Gilbert Adair in the 1990s as A Void. In the case of Dear Reader — original title La liseuse — British readers have had to wait just two years for the translator David Bellos to deliver a close reimagining of Fournel’s work. In the Afterword, the author discloses the constraint under which Dear Reader was written.

It struck me that the subject implied a reflection on the future of reading. It is probable that one of the possible forms of reading in the near future will be interactive: readers will enter into the body of the text and adapt it to their taste … That is why I decided to give my book (probably one of the last of its kind) a fixed form based on its character count, so that anyone entering it to change a single letter will destroy the entire project.

In other words, Fournel has tried to future-proof this book against the ravages of readers, be they electronic or human.

To this end, Dear Reader is shaped like a sestina, ‘a poetic form invented in the 12th century by the troubadour Arnaut Daniel’ and ‘the entire composition makes a poem of 180,000 signs (including spaces)’. The extent to which this endeavour is a successful one is moot — or perhaps it’s just too soon to say. However, this should not deter anyone from reading Dear Reader in whatever way they see fit. When the book was published in France it was widely acclaimed as a satire; but while it is frequently very funny, anyone with experience of editorial meetings, author lunches, sales conferences or Waterstones’s MD James Daunt (who makes a cameo appearance on page 123) will soon realise satire is pretty thin on the ground. In reality, Dear Reader is largely factually accurate. It is the most truthful account of literary ennui I have ever read.

Here is Dubois’ definition of the job of the editor:

Find a famous writer who doesn’t cost too much, who’s been sold in advance, is talented and nice, loyal, productive, timely, who drinks only a little, is modest, amusing, handsome, attentive to personal hygiene and who never drops below 300,000 copies.

Not much satire there. Yet in another way Dear Reader represents the triumph of hope over experience. For however jaded Dubois, or perhaps Paul Fournel himself, may have become by the irksome business of producing and selling books, his belief in them is fundamental and his appetite for reading remains insatiable. Dear Reader is a clear-eyed and unsentimental love

letter to the form. Whether read as a sestina, a satire or a eulogy, it is a quietly remarkable little book.

Comments