The Avant-Gardists tells the story of the small group of brilliant, punky outsider artists who, after the Bolshevik coup in 1917, to everyone’s amazement suddenly found themselves holding important posts in government (as if Sid Vicious were made minister of education). They were soon demoted, and by the end of the 1920s persecuted or driven abroad. Yet news of their breathtaking originality spread internationally, playing an important role in transforming not only our understanding of art, but the aesthetics of modern life, from buildings to household objects, textiles to the printed word.

Sjeng Scheijen has written an exhilarating history of the movement, illuminated by new research and insights, and with many comic moments amid the unfolding tragedy. Most enjoyable is the vividness with which he conjures up the personalities in the group, in particular the two great rivals Kazimir Malevich and Vladimir Tatlin. There’s a touch of Laurel and Hardy about the pair: Tatlin, tall, gangly and morose, and Malevich, small, roly-poly and permanently speechifying. Both were always up for a fight and categorically opposed to any compromise. Wassily Kandinsky and Marc Chagall, older and less combative, float slightly above their tussles, while a crowd of young artists, such as El Lissitzky, Alexander Rodchenko and Varvara Stepanova, each brilliant in their own right, passionately support first one, then the other.

Before the Revolution, the Futurists – as they were known; the avant-garde wasn’t a commonly used term then – were a constant source of outrage for the papers, with their painted faces, topless women and men with half their beards shaved off. Their shows attracted few visitors. Yet by 1916, they had already exhibited pieces exploring almost all the 20th century’s artistic breakthroughs: abstraction, installations, performance and conceptual art.

Most Bolsheviks were actively opposed to non-objective art, while the new commissar for enlightenment in 1917, Anatoly Lunacharsky, had written a series of hostile articles in which he called the group ‘deranged idiots’. Scheijen’s analysis of the shifting dynamics is fascinating. Lunacharsky, recently returned to Russia from exile, found it hard to persuade some of the more mainstream artists to cooperate. At least the avant-garde were outspokenly in favour of the idea of Revolution, even if they weren’t Bolsheviks – in fact weren’t really political at all. The turning point came in April 1918, however, when Lenin abruptly decided that the cities of Russia needed to look revolutionary, as Tommaso Campanella had described in his utopian treatise The City of the Sun. Lunacharsky, anxious to deliver, turned to the radical young artists not for their art, but for their energy and enthusiasm. In short, as the critic Abram Efros noted: ‘Futurism was not necessary, but the futurists were.’

In October 1918 the avant-gardists successfully stage-managed huge festivals in Moscow and Petrograd, bringing their art to the notice of a much broader public for the first time. Unfortunately, the masses weren’t keen, commenting on the revolutionary street decorations with letters to the news-papers saying things like: ‘Vomit! It makes me sick to my stomach.’ Lenin himself called an early Futurist sculpture ‘decadent garbage’.

Sacked from their ministerial posts, many radical artists continued to work in arts education during the 1920s. They were partly protected by their flourishing international reputations, which were useful to the nascent USSR – left-wingers across Europe were won over by the image of the Soviet Union as an ideal socialist state, led by scholars, engineers and artists. These were years of magical creativity for the avant-garde, that saw the unveiling of Tatlin’s tower, the development of constructivism by Rodchenko and others, and Malevich’s Suprematist group, Unovis, in Vitebsk. A lovely scene captures the eccentricity that was an integral part of the movement: Malevich’s arrival at the art school in Vitebsk, obviously keen to make an impression. He slowly and silently came down the stairs, swinging his arms in large circles. The students were so baffled by his arm-swinging entrance that they later referred to it as ‘the suprematist movement’.

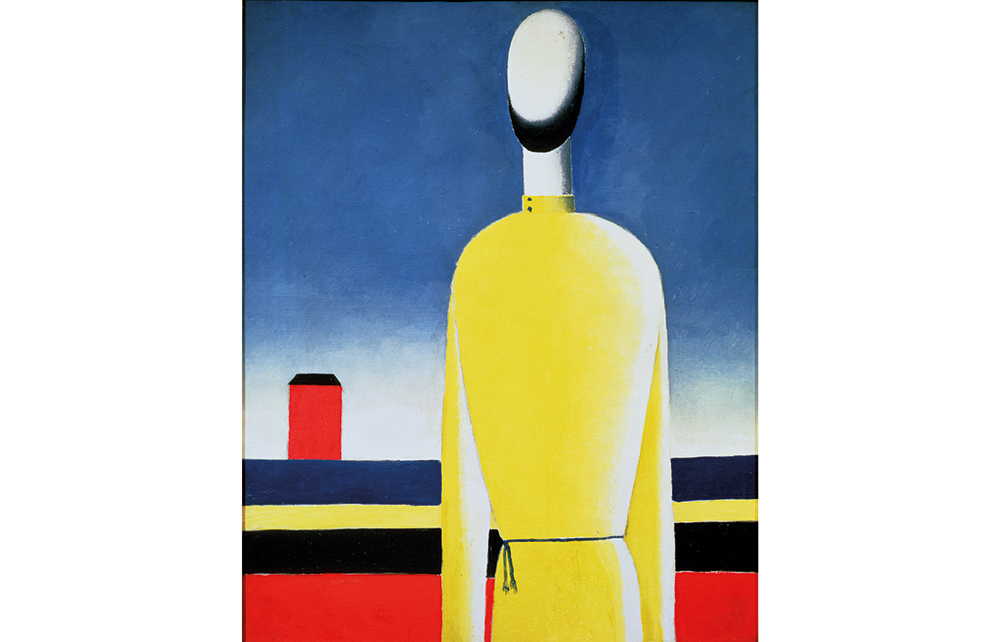

Their jokiness, quirks and provocations are some of the most endearing aspects of the avant-gardists. They were also the first to be crushed by the increasingly confident Soviet state, which soon turned to the clumsy propaganda known as socialist realism. By the early 1930s, Malevich had returned to a more figurative style; his faceless peasant figures in a flat landscape are among the great tragic masterpieces of the Soviet Union, heavy with totalitarian dread.

Meanwhile, one of Tatlin’s final artworks was an extraordinarily touching conceptual piece – an individual flying machine with vast silk wings like a magical bird. Reviewers, missing the point, were scathing of its inability to be airborne for longer than a few moments. Yet I think Maria Antonova, writing in 2017, was more perceptive when she noted: ‘It might feel like flying in your sleep: running and then lifting off the ground.’ ‘Letatlin’ was created during the most bloodthirsty period of Soviet rule, when technology in the hands of a murderous clique seemed intent on crushing the individual entirely. Has a more moving monument to our human longing for, and inability to achieve, true freedom ever been created?

Comments