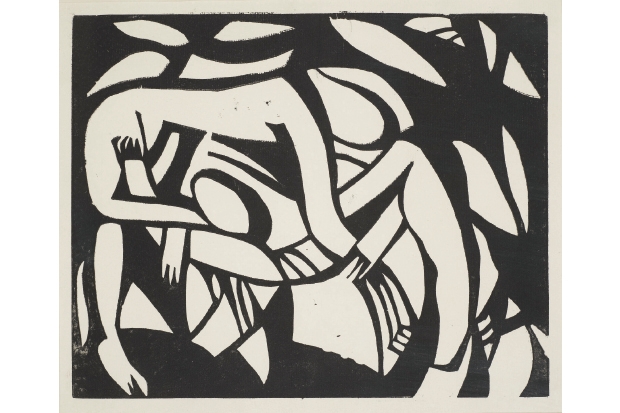

One evening before the first world war, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, fired by drink, tried out such then-fashionable dances as the cakewalk and the tango, ‘his eyes burning — his hair wild’. What was funny about this spectacle, his companion Sophie Brzeska confided to her diary, was not so much the dances as the sight of the dancer himself, ‘the young bear like nothing on earth with his seven league boots jumping in the air like an extraordinary buffoon’. It is a description that evokes many works displayed in a delightful little exhibition, New Rhythms, at Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge. This marks the centenary of Gaudier-Brzeska’s death; he was killed in action on 5 June 1915, aged 23. But it is not exactly a memorial show. Instead it examines an intriguing subject: how crazy early modern artists were about music and movement. This phenomenon was not limited to the early years of the 20th century, nor to Gaudier and his circle (a young French expatriate living in London, he added ‘Brzeska’ to his name in homage to Sophie). Piet Mondrian, the austere master of geometric abstraction, was one of art history’s most improbable swingers — in the musical sense, at least — being an avid dancer to the sounds of jazz and boogie-woogie. But Gaudier was particularly explicit about the importance of rhythm in the arts. It was, he believed, the crucial factor. ‘The great thing’, he wrote to Sophie, ‘is that sculpture consists in placing planes according to a rhythm’. And the same, he added, applied to all the other arts: in painting you had to place colours rhythmically, in literature stories. Or, as the title of a Duke Ellington piece proclaimed, ‘it don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got that swing’. Gaudier and Ellington had a point. Often it seems to be lack of a compelling rhythm that makes prose, for example, fail to flow. An ability to perceive and hold a rhythmic pulse, collectively, seems to be one of the very few attributes that separates human beings from the rest of the animal kingdom. Trained elephants can keep a steady beat individually, but not as a band; whereas people can scarcely prevent themselves from tapping their toes to an infectious rhythm. Early modernist sculpture, however, might seem one of the trickier idioms in which to inject a sense of irresistible swing. And, Gaudier evidently didn’t find it easy. His ‘Red Stone Dancer’ (c.1913–14) is vigorously simplified — the eyes and nose become a triangle — but is executing less a quick step than a grizzly-bear lumber. There is a similarly sluggish feel to his ‘Wrestlers’ relief from the same period. He seems to have seen this sport as a sort of violent and virile male dance, describing ecstatically a match he had seen in which the two contestants had reached ‘such a state of perfection that one can take the other by the foot and, without exaggeration, can whirl him five times round and round himself, and then let go so the other flies off and falls on his head’. Rather than such quicksilver action, ‘Wrestlers’ suggests a slow-motion encounter between a pair of pandas. The naked and willowy ‘Dancer’ (1913) is at once more naturalistic and more successful in conveying motion. Some of the works by Gaudier’s contemporaries, included in the exhibition, do even better in this respect; Rodin’s extraordinary sculptural sketch of Nijinsky (1912) positively jumps with energy. Nonetheless, Gaudier did have rhythm; that is made clear above all by his marvellous drawings. He drew at an amazing rate — he described doing 150 drawings in an evening at a life class, while his fellow students executed two or three — and his line had marvellous speed. There are some splendid examples in the exhibition, and more — interspersed with a few by artists of today such as Rachel Whiteread and Antony Gormley – next door in the lovely Kettle’s Yard house (just about the most perfect modernist interior in England, and one of the very few to have been preserved). New Rhythms puts Gaudier’s poignantly brief career in context, surrounding his works with those by fellow members of the British avant-garde that flared briefly in the years before 1914, including Epstein, Wyndham Lewis and David Bomberg, and others based in Paris. It makes clear that he was a fledgling artist of huge promise, and some great achievements. I would nominate the slightly comic evocation of nature red in tooth and beak, ‘Bird Swallowing a Fish’ (1914), as his masterpiece, although I’m not quite sure it fits into the dancing and fighting theme of the show. If Gaudier was correct — and I think he was — the arts are always concerned with rhythm. But motion was a particular obsession in the early 20th century, perhaps because the world then must have seemed visibly to be speeding up. He belonged to the first generation to grow up with film (the first demonstration of the new medium was in Paris in 1895, when he was three years old). The motor car and the airplane appeared in rapid succession, followed by those African and Latin American dances, the cakewalk and tango. Things were going faster and faster. It all ended in the cataclysmic impact of the war, which ended Gaudier’s brilliantly accelerating life far, far too early.

Martin Gayford

He’s got rhythm

It’s hard to inject swing into modernist sculpture, but Gaudier-Brzeska managed - just about

issue 02 May 2015

Comments