The curtain is already up at the start of Ted Huffman’s new production of Eugene Onegin. The auditorium is lit but the stage is in darkness and almost bare. Gradually, as Tchaikovsky’s prelude sighs and unfurls, the stage brightens and the theatre grows dim. But not before Onegin (Gordon Bintner) – tousle-headed and in a designer suit – has walked out, bowed to the house and retired to a chair at the back of the stage, to wait for the story to call him to life.

Any competent maestro can whip up a big noise, but it’s a lot harder to make meaning out of silence

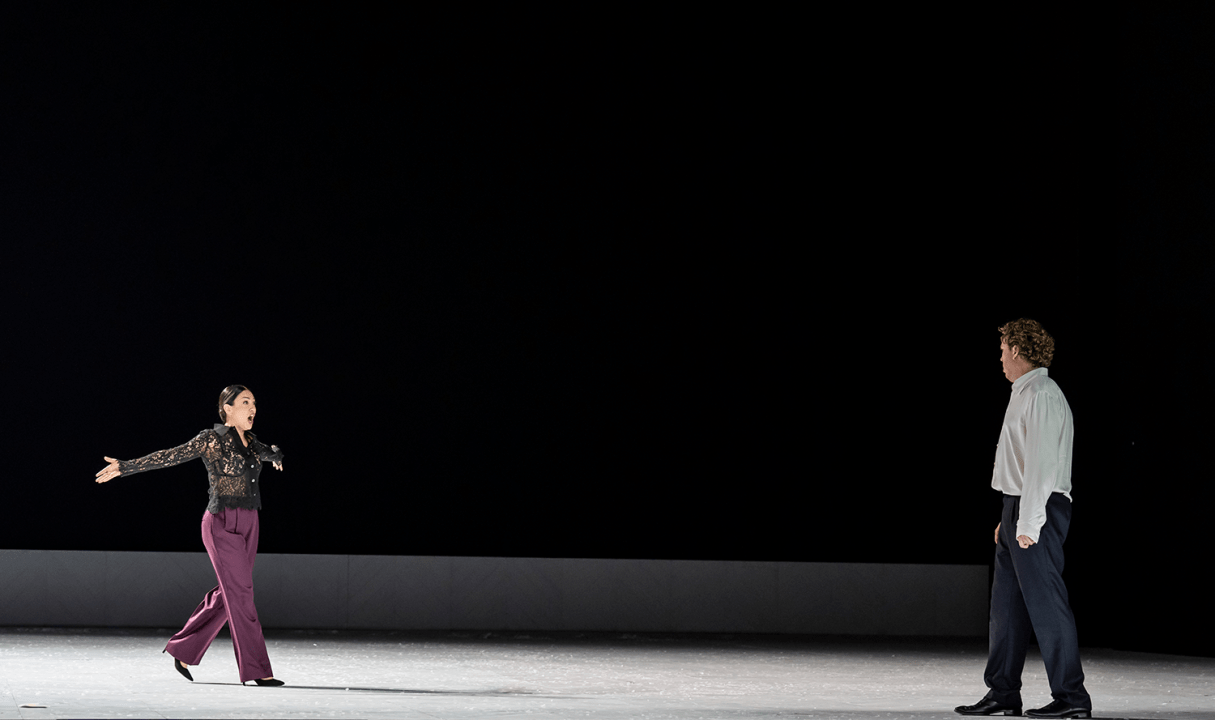

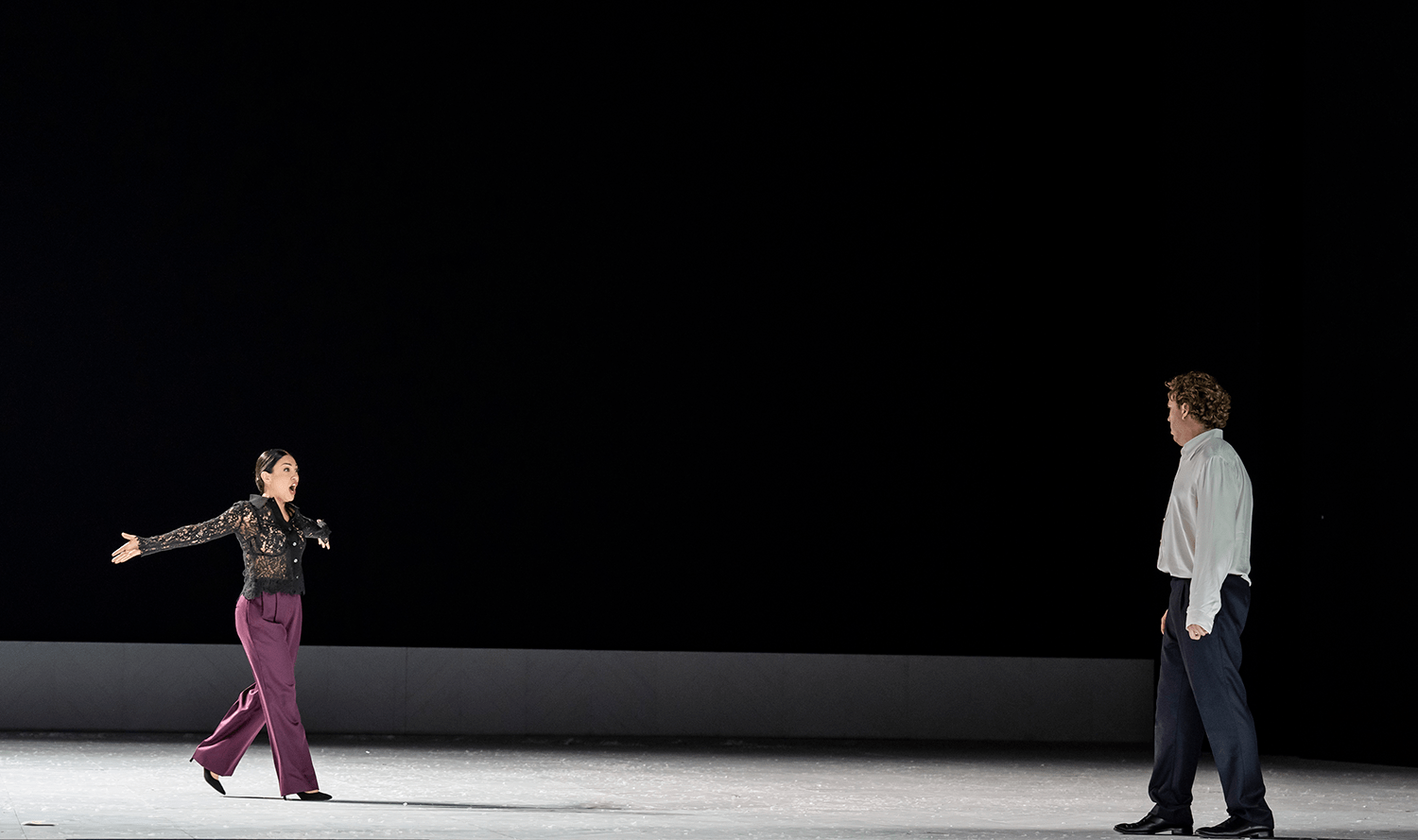

Russophiles have grumbled for years about the way Tchaikovsky trimmed and tidied Pushkin’s raffish first-person narrative into seven self-contained ‘lyrical scenes’. From the start, Huffman seems determined to tug and tear at those graceful patchwork pieces; to unpick the opera’s relationship with its source material, and with us, its audience. The setting (if you can call it that) is determinedly contemporary and monochrome. There’s swirling mist instead of scenery and everything plays out against one of those black backdrops that look cool in the production photos but give you eyestrain over the course of an evening.

Still, there’s method in all this minimalism: it throws the focus wholly on to the characters and here, Huffman is superb. These are performances filled with living, heartbreaking expression. Tatyana’s features become a mask as Onegin delivers his rebuff at the end of Act One (surely the iciest friend-zoning in all of opera). Amusement, mortification and pain flicker across Bintner’s face as he tries to talk Lensky (Liparit Avetisyan) down from his fatal tantrum. The countless little glances, gestures and smiles that flow between the women of the Larin household are a masterclass in delicate naturalism.

So we see a functioning, affectionate family; with Huffman’s subtle direction matched by performances that should be compulsory viewing for anyone who still thinks that opera singers can’t act. Madame Larina (Alison Kettlewell) and Filipyevna (Rhonda Browne) have rarely seemed less like plot devices, and more like living, loveable human beings.

Perhaps the most striking aspect of the production is the way Huffman has expanded and opened out the role of Olga (Avery Amereau). Here, she’s a silent but enthusiastic accomplice in Tatyana’s letter-writing; which is just how devoted teenage siblings probably would behave. Far from violating the spirit of the opera, Olga’s expanded role helps liberate the emotional subtext of some of Tchaikovsky’s tenderest music.

So far, so persuasive. But Huffman’s attempt to remake Onegin himself involves more radical surgery. He rewrites the duel scene to shocking effect (absurdly, the two sisters are present), so that the broken Onegin of Act Three is grappling with private trauma rather than carrying the mark of Cain. This is directorial intervention on a different level from Huffman’s transformation of Monsieur Triquet (Christophe Mortagne) into a sinister clown, or the weird charity-shop retro outfits and relentless cheek-kissing – mwah! mwah! – that make the choral scenes resemble a staff party at the Barbican. For what it’s worth, I’m inclined to think that it worked, or at least that it was a price worth paying for a heartfelt and thought-provoking evening of music theatre.

But other opinions are available, and you have until 14 October to form your own. If nothing else, you can expect passionate and intelligent singing across the cast: a credibly anti-heroic Onegin from Bintner, a searing, articulate farewell aria from Avetisyan and an unusually ambiguous Tatyana in Kristina Mkhitaryan, whose big set pieces had the focus and nuance of chamber music – an effect enhanced by spacious, refined playing from the Royal Opera House orchestra under Henrik Nanasi. On the first night, Brindley Sherratt stepped in at short notice as Prince Gremin. Sherratt never gives a disappointing performance, and he received a well-deserved ovation at the end. Huffman, meanwhile, was booed. British opera-goers lead very sheltered lives.

In Manchester, Kahchun Wong gave his first concert as principal conductor of the Hallé orchestra, taking over from Sir Mark Elder who stepped down just a few weeks ago after 24 years in the post. Elder has left Wong an orchestra and (by the look of it) an audience in enviable health; few if any UK symphony orchestras currently come close for finesse and beauty of sound.

Both qualities were on display in a suite from Britten’s The Prince of the Pagodas, but Wong’s own voice was more discernible in Mahler’s First Symphony. On this showing, Wong has a Rattle-like ear for detail, as well as an impressive command of scale. The massive stillness of the opening bars seemed to extend like a seam of quiet concentration beneath the whole symphony, throwing the foreground drama into vibrant relief. Any competent maestro can whip up a big noise, but it’s a lot harder to make meaning out of silence. Wong has the knack: he’s one to watch.

Comments