Although I am an admirer of Dulwich Picture Gallery, and like to support its generally rewarding exhibition programme, I will not be making the pilgrimage to see its latest show, Norman Rockwell’s America.

Although I am an admirer of Dulwich Picture Gallery, and like to support its generally rewarding exhibition programme, I will not be making the pilgrimage to see its latest show, Norman Rockwell’s America. This is not just because it’s quite a hike to Dulwich for me, involving a bus, a train, another bus and another train (anything in excess of three hours from door to door), but also because I don’t think the trip will be worth it. I’ve been impressed by the series of monographic exhibitions Dulwich has mounted in recent years on English artists — Sutherland, Piper, Sickert and most recently Paul Nash — but the other side of the programme is an interest in American artists which I can’t always share.

Don’t get me wrong: I love the best of American art, and find it deeply exciting. But Dulwich is a small museum, inevitably of limited resources, and its ‘special relationship’ with American Art (to be applauded in theory) does not extend to a single disinterested sponsor who will pick up the bill for procuring only the finest examples of that nation’s artistic output. As a consequence, Dulwich has to cut its coat to suit its cloth and in effect take what’s available — corporate collections which reflect more glory on the corporation than on the artists represented, minor museum accumulations, or packages from wealthy American Foundations which desire the imprimatur of a prestigious English exhibiting venue. Oh, for the days when the CIA backed European shows of Abstract Expressionism in the cause of cultural imperialism!

I’m all in favour of an English Museum devoted entirely to American Art, and paid for by American largesse, and perhaps then we would see proper shows of such relative unknowns (in this country) as Wayne Thiebaud (born 1920), Milton Avery (1885–1965), John Marin (1870–1953) and Marsden Hartley (1877–1943). And I could make a substantial list of others suffering a similar neglect here. Recently, I received a wodge of publicity material about the American Museum in Bath, which celebrates its 50th anniversary this year. Will this not fit the bill? I hear you exclaim. But it’s a collection of some 15,000 items devoted to the decorative arts, housed in Claverton Manor, thanks to the remarkable generosity of two American citizens, Dallas Pratt and John Judkin. Here you will find fancy gowns and Shaker furniture, a superb collection of quilts, Cigar-Store Indians, Navajo rugs — but only a very few paintings and sculptures. No, there needs to be another museum to do justice to the breadth and originality, the sheer achievement of American art.

Norman Rockwell (1894–1978) is not an artist who deserves an exhibition in a British museum. He was an American illustrator best known for his cover paintings for the Saturday Evening Post, for which he produced more than 300 in the period between 1916 and 1963. Rockwell became a master of reactionary self-image, adept at recreating American family life of a bygone age, mostly with a rural slant. Escapism, pure and simple, and illustration, not art. He may have been a skilled painter (he was certainly a professional), but his illustration work kept the artist in him thoroughly at bay. His artwork was always intended to be seen in reproduction, so there’s no good reason to show us the originals now. When there are so many more important artists to exhibit, why give Rockwell the limelight?

Likewise, I was not especially wowed by the Saul Steinberg exhibition at Dulwich, mounted with the full support of the all-powerful Steinberg Foundation, back in 2008, though I know Steinberg has many devotees. Once again, much of his work was made to be seen in reproduction, and I don’t think museums need to put on exhibitions of the originals in such cases as these. The same could be said of photographs — much better to sit at home in the comfort of your own armchair and peruse a high-quality volume of reproductions than fight your way round a crowded paying exhibition and be rewarded only with glimpses. More real art, please.

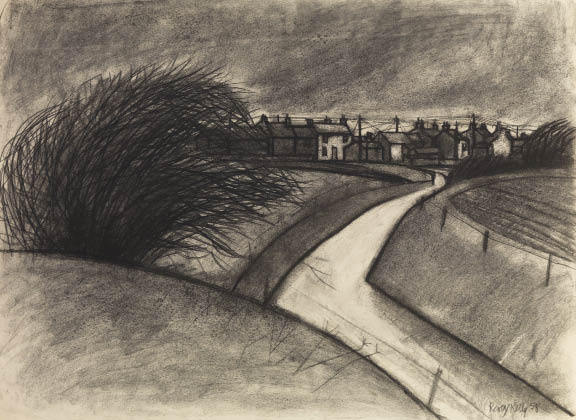

By way of complete contrast, I have no hesitation in recommending the work of Percy Kelly (1918–93). Kelly was a strange and somewhat tortured man who also happened to be a brilliant draughtsman. Not many people in his lifetime knew this because he refused to exhibit or sell his work, and used to hide it away if even an admiring visitor (such as L.S. Lowry) came to call; he was convinced that Lowry would steal his ideas. Born in Workington, Cumberland, Kelly managed to exile himself from his beloved home-county — partly through a temperamental inability to earn money — first to Pembrokeshire and finally to Norfolk. The best of Kelly’s output is the grand series of powerfully mesmeric charcoal drawings he made in the late-1950s, mostly of landscape. They bear comparison with the cream of Sheila Fell’s work (which he knew and admired), but have a solidity and conviction, an earthbound magic, which is all his own.

Kelly’s determination to hold on to his pictures (‘I would rather starve than sell one piece of my work’) is immensely refreshing in today’s climate, where art students are taught salesmanship and presentation rather than how to draw or paint. But it has meant that his work is widely unfamiliar. This is changing now: the current show at Messum’s is the second in London and a biography of Kelly by his long-time champion, the Cumbrian dealer Chris Wadsworth, is due out later this year.

Very last chance to see Cézanne’s Card Players at the Courtauld Gallery (until 16 January), which I regret not having written about earlier. A fascinating in-depth examination of one particular subject favoured by Cézanne, it brings together three of the original five paintings on the theme with a number of related oil studies as well as preparatory drawings and watercolours. The loans come mainly from America and Russia and will probably never be repeated, so this unique gathering needs to be witnessed. Artists, in particular, have been loud in its praise — nearly always a good sign.

Comments