Leonard Rosoman is not a well-known artist these days. Many of us will, however, be subliminally familiar with his mural ‘Upstairs and Downstairs’ in the Grand Café at the Royal Academy, painted in 1986 when the artist was in his early seventies. Two worlds are portrayed with a degree of satire — dressy guests arriving for the private view of the Summer Exhibition and below, in sober grisaille, Royal Academy Schools students engaged on life drawing. ‘Upstairs and Downstairs’s wit and perspectival acuity notwithstanding, its status as a mural makes it easy to overlook, an extended splash of colour behind the Café’s lunch counter.

Leonard Rosoman is worth rediscovering. He was a fine war artist and a brilliant illustrator. But he does not fit neatly into the fragile story of British modernism. Abstraction passed him by, and even though he was a figurative painter he was never part of the School of London, the term invented in 1976 by R.B. Kitaj to describe himself, Michael Andrews, Frank Auerbach, Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud and Leon Kossoff. Although we can draw a comparison with Michael Andrews — both created ambitious narrative multi-figure paintings and both had an elegant way with acrylic — Rosoman did not offer the visceral explorations of reality associated with Auerbach, Bacon and Freud.

But he had a uniquely strange vision that from the late 1950s onwards conflated pop art and Victorian problem pictures. At the heart of the Pallant House exhibition Leonard Rosoman: Painting Theatre that I have curated are 16 rediscovered pictures based on John Osborne’s controversial 1965 play A Patriot for Me.

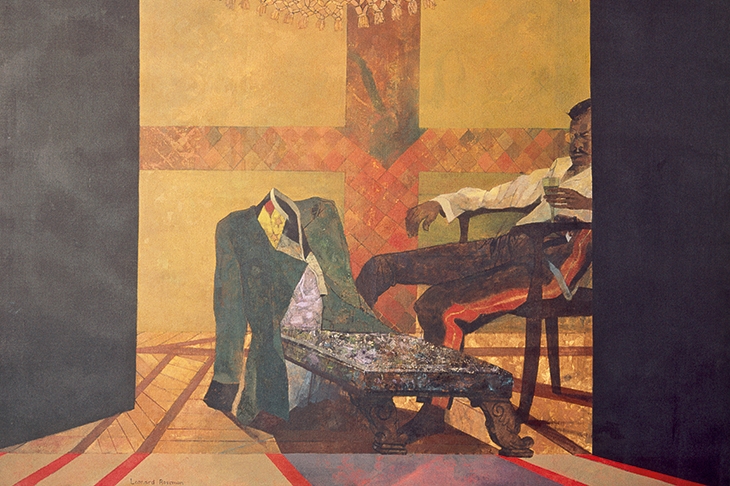

Rosoman and Osborne had a tender friendship that blossomed in the early 1960s, with Rosoman spending happy, bibulous weekends in Sussex with Osborne, his then wife Penelope Gilliatt, and, inter alios, the opera director John Copley and Gilliatt’s sculptor sister Angela Conner. When Rosoman attended the first night of A Patriot for Me he was captivated and Osborne gave him tickets for a fortnight of performances during which he drew and took notes. Two years later, taking advantage of the fast-drying qualities of acrylic and using a mannerist palette of colours, Rosoman created 40 paintings and gouaches that offer unforgettable images of the play — the Royal Court’s director George Devine in drag as the aristocratic and camp Baron von Epp, Rosoman’s friend Jill Bennett as the treacherous Countess Sophia, and the German actor Maximilian Schell playing the doomed Colonel Redl.

A Patriot for Me was staged at the Royal Court as a private members’ club production directed by Anthony Page. The Lord Chamberlain Lord Cobbold had demanded extensive cuts, eventually refusing the play a licence because of its explicit homosexual content. One scene Cobbold wanted to remove in its entirety was the absolute heart of the play. Osborne had fantasised to George Devine and Christopher Isherwood about the curtain rising on an exquisitely turned-out crowd at a fancy-dress ball: the audience would only gradually grasp that all these elegant protagonists were men. Osborne’s drag-ball scene is recorded in two of Rosoman’s largest and most complex canvases. They are among the finest pictures he ever painted, looking back to Velazquez and Goya but anticipating the unnerving narrative world of Paula Rego.

None of Rosoman’s A Patriot for Me paintings have been shown publicly for some 40 years. Osborne and Jill Bennett, whom Osborne married in 1968, bought 11 of the series but, as their marriage failed, the famously hot-tempered Bennett took to pulling them off the walls and throwing them at Osborne. Rosoman’s favourite framer Robert Sielle was called in to fix the damage. The playwright kept one of the finest paintings, a large night-time study of Maximilian Schell as Redl, but its pendant, one of several portraits of Jill Bennett as Countess Sophia, has still to surface. Indeed, about half the paintings Rosoman based on A Patriot for Me are lost and those that we see at Pallant House were difficult to trace.

Rosoman’s extraordinary paintings capture a moment in theatrical history and memorialise a clash with 1960s cultural conservatism. The story of Alfred Redl’s downfall was unacceptable to Lord Cobbold, just three years before the Lord Chamberlain’s archaic role as theatrical censor was abolished. And the fact that Osborne wrote a love scene between Redl and a young soldier that ended in violence, the subject of two remarkable paintings by Rosoman, meant that no British actor would take the part of Redl. Such was the climate of fear before the 1967 Sexual Offences Act.

The paintings also demonstrate the Janus-faced nature of Rosoman’s own talent. The A Patriot for Me pictures are a magnificent extension of the theatrical conversation piece, the genre first developed by William Hogarth and Johann Zoffany. Rosoman made the theatrical conversation piece contemporary — paint captures greasepaint and thespian artifice, recording for all time Osborne’s genius, and reminding us of a theatrical controversy and of the minatory scattergun powers of the Lord Chamberlain’s office.

Comments