There isn’t a luxury ship that wouldn’t look better for having sunk. Barnacles and rot bring such romance to the lines, like spider webs in the sea. Even the decay Damien Hirst has applied to his Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable is quite appealing. It crawls over many of the objects that he claims to have salvaged from a shipwreck of the 1st or 2nd century ad. A mouldering Mickey Mouse. A bronze portrait of the artist encrusted in faux-coral. It’s Trimalchio meets Disneyland meets Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea.

It so happens that Hirst’s exhibition at the Punta della Dogana and Palazzo Grassi in Venice (until 3 December) coincides with a search for another wreckage, this one truly ancient. Divers are currently scouring the bed of Lake Nemi near Rome for a pleasure boat once owned by Caligula. Two of the late emperor’s boats were raised from the same lake in the early 1930s upon the orders of Mussolini, only to be destroyed during the second world war. Fishermen say an even bigger boat is still down there. Caligula’s wreckage may be just the rival Hirst’s treasure boat needs.

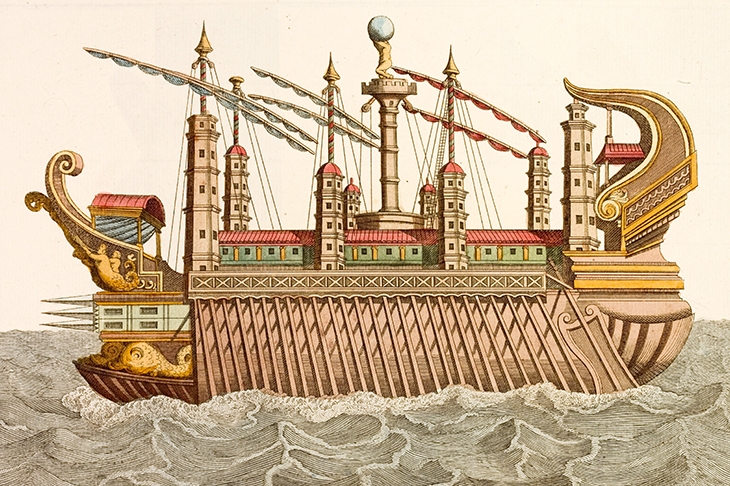

Is there something a bit Caligula-like about Damien Hirst? The emperor’s interests are said to have included incest with his sisters, summary executions and expensive large-scale projects. It’s the third one really. Caligula apparently spent the entirety of his predecessor’s fortune in the first year of his rule alone (37 ad). Most of that money went on aesthetic, attention-grabbing constructions. Mountains were lowered, tunnels driven through rocks, villas thrown up. As for ships, Caligula’s biographer Suetonius says he kept luxurious galleys in Campania with ten banks of oars, jewel-bedecked sterns, multicoloured sails, baths, porticoes, dining rooms, vines and fruit trees. The two ships discovered at Nemi in the last century proved what was possible. Each measured more than 70 metres long (twice the size of an Athenian trireme) and had mosaics, marble walls, columns, piston pumps and lead pipes. As his ship drifted over the lake, Caligula could wallow in hot and cold baths perfumed with bath oils — just as Suetonius said he did.

No less extravagant, Hirst admits to having spent in the region of £50 million on his ancient wreck. The ship he has commandeered was, he says, transporting the treasures of a wealthy former slave to a temple when it foundered in the Indian Ocean. Among the 190 pieces transported to Venice are portrait busts with emerald eyes and Medusa heads made from gold, malachite, crystal glass and bronze. Precisely the sort of things Caligula would have liked. The emperor had a bronze Medusa head of his own fitted to the rudder pole of one his ships. A rare survival of the fire at Nemi, the head evokes the time Caligula reputedly hurled a crowd of people into the water and picked them off with poles and oars as they tried to cling to a ship’s rudder.

The line between history and myth is hopelessly blurred. Bits of Caligula’s biography make the mythology of Hirst’s exhibition look credible by comparison. Hirst’s ship may be mythical — its name, Apistos, means ‘Untrustworthy’ as well as ‘Unbelievable’ in ancient Greek — but so were Caligula’s ships until some evidence was found. Hirst only further muddies the water between myth and reality.

He does so in some surprisingly conventional ways. Several of his treasures take the shape of sea monsters, such as the Cetus that terrorises poor Andromeda while she is chained to the rock. As ever, the question is whether these are simply allegories for the fear of seafaring. The monsters are defeated by being turned, Medusa-like, to stone or bronze sculptures.

It’s not surprising that Venice continues to attract commissions inspired by the sea. It may no longer be the naval capital of the Mediterranean, but Venice’s water still lends itself to art that commemorates its naval prowess. Hirst’s shipwreck follows Icelandic artist Ragnar Kjartansson’s The S.S. Hangover, exhibited at the Biennale in 2013. Sailing and docking in the Arsenale, Venice’s historic shipyard, Kjartansson’s vessel was a reconditioned fishing boat that drew upon the traditions of the Vikings, Greeks and Venetians, and carried a crew of musicians. The process of peeling back — or, in Hirst’s case, applying — the layers of decay to give a boat new life naturally throws up questions about its past. Ships and shipwrecks will always conjure up their own myths.

Those summoned by the prospect of uncovering Caligula’s ship are particularly juicy. Music, orgies, an early super yacht supplied with prostitutes. It was Caligula’s habit to invite married couples to dinner, eye up the wives, and leave the dining room with those he most liked the look of. When he returned to the dinner table looking discernibly dishevelled, he would give his other guests a detailed description of how each woman was. Just imagine that on a boat where there was no escape.

Is Hirst’s boat any less real than Caligula’s orgies? It’s the kind of question he longs to be asked. He offers up his wreckage as an invitation to choose myth over history. Believe what you like, he says. Well, here’s what I believe. In a world in which myth and history collide, Hirst has alighted upon a peculiarly well-documented field. He has read extensively on ancient shipping routes. He imagines a treasure-laden vessel heading north through the Indian Ocean towards the Red Sea. In Caligula’s time, the 1st century ad, ports such as Myos Hormos (Quseir al-Qadim) on Egypt’s east coast were bustling with trade. Ports were where the real treasure was: frankincense from South Arabia, silk and black pepper from India, wine from Rome.

Hirst’s treasures belong to the world of louche pleasure boats, but are born of that trade. Their influences are Greek and Roman, Egyptian and Far Eastern, American and comic book. They belong to a man who has seen the world but failed to appreciate its subtleties. Some are beautiful, most are brash, even beneath the barnacles. And yet, so far, the mythology of Hirst’s wreckage rings true. A merchant would buy black pepper; a former slave what he believed made him look like an emperor. Only Damien Hirst could dare to express how tacky and extravagant the ship of Caligula could be.

Comments