Whenever the words ‘stucco house’ appear in the newspapers, you can be certain the occupiers have been up to no good. The Russian kleptocrat in his stucco palace in Mayfair. The shamefaced prime minister seeking refuge in the stucco mansion of a party-donor chum. The disgraced wife-throttler with a stucco terrace in Eaton Square. In each case, it is miscreant stucco, offshore-trust stucco, stucco hiding corruption and foul play behind whiter-than-white, butter-wouldn’t-melt façades.

Almost from the moment the first stucco suburbs — Belgravia, Pimlico, Bayswater, Paddington, Notting Hill, North Kensington — went up in the 19th century, modelled more or less devotedly on John Nash’s Regent’s Park scheme, ‘Stuccovia’, as it was called, was treated with suspicion and sometimes derision. Those runs of piano-key houses were too smooth, too bourgeois, too bland, too samey, too suburban. This, when any street west of Marble Arch was thought to be the outer reaches of civilised London. ‘People who like this sort of thing will find this the sort of thing they like,’ said the satirist G.W.E Russell of small-minded, ‘excruciatingly genteel’ Stuccovia in 1902.

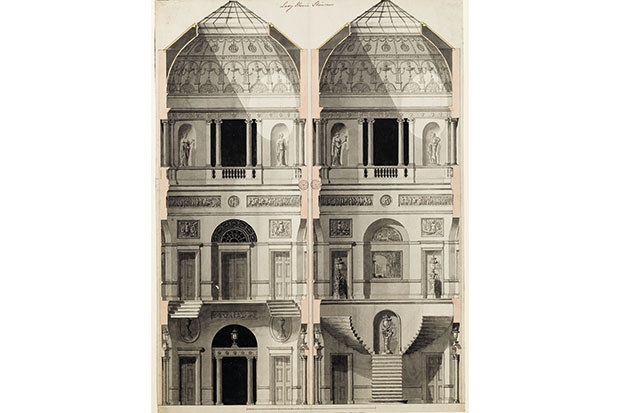

There are two sorts of stucco (which is a type of plaster). The first is the delicate, filigree stucco work of Italian stuccatori craftsmen: lace-like wedding-veil patterns applied to ceilings and drawing-room panels and popularised in this country by Robert Adam. Adam was the master of intricate stucco-work ceilings, not always white, but often coloured in his palette of pinks and blues. Horace Walpole mocked Adam’s stucco daintiness as ‘gingerbread and sippets’, but clients adored it.

Less so Adam’s external stucco work. Frances Sands, curator of a superb new exhibition, Robert Adam’s London, at Sir John Soane’s Museum, cites Kenwood House where Lord Mansfield complained that far from being a cheap alternative to stone, the stucco needed so much upkeep and redoing that ‘it would have been cheaper to cover it all in Parian marble’.

There were similar problems with Adam’s stucco at 11 St James’s Square and at the Adam brothers’ Adelphi scheme.

This was slap-it-on stucco, stucco as the cake icing on so many Georgian and Regency streets and vaguely Italianate Victorian terraces. External stucco could be grand — as it was in the hands of Nash and Adam at their best — or a cheap way of making shoddy, rapidly built houses look like Bath or Portland stone. The architectural historian John Summerson thought stucco suggested ‘faintly and agreeably, the artificiality of powder and rouge’. He is too kind to say that like heavy make-up, stucco often hid buildings that were much pocked and wrinkled. It is this sort of stucco, smothering street after street — Stucco Square, Upper and Lower Stucco Place, Stucco Gardens, Stucco Mews West — from the 1820s that comes in for such a drubbing.

Already in 1871, editorials in the Times were weary of ‘eternal stucco’. The paper hailed the first brick-and-terracotta buildings of the South Kensington Museum — now the V&A — as sights for stucco-sore eyes. By 1879 the Times was running special reports on unscrupulous builders who covered ‘jerry’ dwellings, unsafe and unsanitary, with stucco, pronounced them ‘improved’ and hiked the rents. It is ‘cracked stucco’, ‘blistered stucco’, ‘dreary stucco’, ‘sham stucco’ and ‘the disfigurement of the country’. The Spectator, in 1875, called stucco ‘immoral’.

In Henry James’s The Princess Casamassima (1886), we know the Princess has sunk in society when she moves from Mayfair to a stucco crescent in — horrors! — Paddington. As far as the Princess’s friends are concerned, ‘The descent in the scale of the gentility was almost immeasurable.’ Madeira Crescent, her new address, is not only ‘shabby’, but ‘mean and meagre and fourth-rate and had in the highest degree that petty parochial air, that absence of style and elevation, which is the stamp of whole districts of London’.

Virginia Woolf, born in a stucco house in Hyde Park Gate, thought stucco stood for merchant middle-class timidity: nice manners, no guts. She resented the ‘pale pompous beauty’ of the Kensington of her youth. When her time-travelling hero-heroine Orlando arrives in the late 19th century she looks at London’s Stuccovia and finds her mind ‘dizzied with the monotony’.

It wasn’t just London, but Bristol, Brighton, Canterbury, Bath, Liverpool, Manchester — a whole country stucco’d from basement to cornice. In Gilbert Cannan’s novel The Stucco House (1917), set in Thrigsby, a fictional Midlands industrial town, stucco becomes something demonic. The stucco house bought by the Lawrie family, wanting to go up in the world but not really able to afford the upkeep, is blamed for all their subsequent misfortune. Jamie Lawrie’s descriptions of the house on Roman Street become more and more hysterical: ‘a great big sarcophagus of a house’, a ‘prison’, ‘hideous and pretentious’, ‘an absurdity of a house, a monstrosity in which it was grotesque to imagine that happiness could dwell’. All because of a marzipan layer of stucco.

Who will speak for stucco? Where are its white knights? Here they come, trotting down the ivory avenues of Regent’s Park: John Betjeman and Osbert Lancaster. To Betjeman, stucco was always ‘creamy stucco’, while Lancaster wrote fondly of his birthplace, the ‘bright creamy’ 79 Elgin Crescent. Lancaster later became a champion of ‘sensible and attractive’ stucco, which harmonised so well with the ‘scenery and atmosphere of the English seaside’.

I’m with the white knights. To my eyes there is nothing so scrumptious as a Jersey-cream, Eton-mess meringue of a house in Maida Vale, revelling in its own whiteness in the Regent’s Canal. In a country that is often grey, stucco is a salamander: when there is sun, it basks in it, glories in it, is white, gorgeous and gleaming against blue skies; when it is overcast, stucco is defiant, it takes what little light there is and shines and smiles, where red brick, steel and concrete frown. Yes, it is prone to falling off in lumps if not maintained. But when pristine, is there a nicer, nobler sight than a stucco crescent? When the pearly gates open on my vision of heaven, it is on an uninterrupted vista, a John Nash utopia, of street after double-cream street.

Comments