Rum is a relatively young drink – 15th century – and still under-appreciated, but at its best can match any whisky or brandy for complexity and sophistication. Peter Grogan enters the darkness

A long time ago a knuckle-dragging ancestor of mine left a gourd-ful of palm sugar out in the rain. Trolling along, the right little speck of yeast eventually came to rest in it, causing the sugar to spontaneously ferment. The result probably didn’t taste too good but it had something that helped the day pass in a pleasant blur.

Fast-forward 10,000 years — at a guess — and that same something can apparently be had from mixing some mashed-up tinned fruit with water, bread (for the yeast), sugar and a dollop of ketchup (to improve the taste) in a zip-loc bag. Of course, you’ll need to stick it up your jumper during the day and sleep on it at night to keep it warm enough to ferment (although in the winter you could pop it behind a radiator). Despite tasting of vomit — with which it has a lot in common — it’s surprisingly popular in US jails, where it’s known as ‘pruno’.

We will climb any mountain, ford any stream to get our hands on some booze. Of all the sources of our sauce, sugar cane must be one of the most unpromising. But, if you can somehow squeeze the juice out of the damn stuff, boil it down — usually to the point of turning to molasses — and then ferment that into some sort of undrinkable beer the result can then be distilled into something that, at its best, can shake its booty with the finest whiskies and brandies.

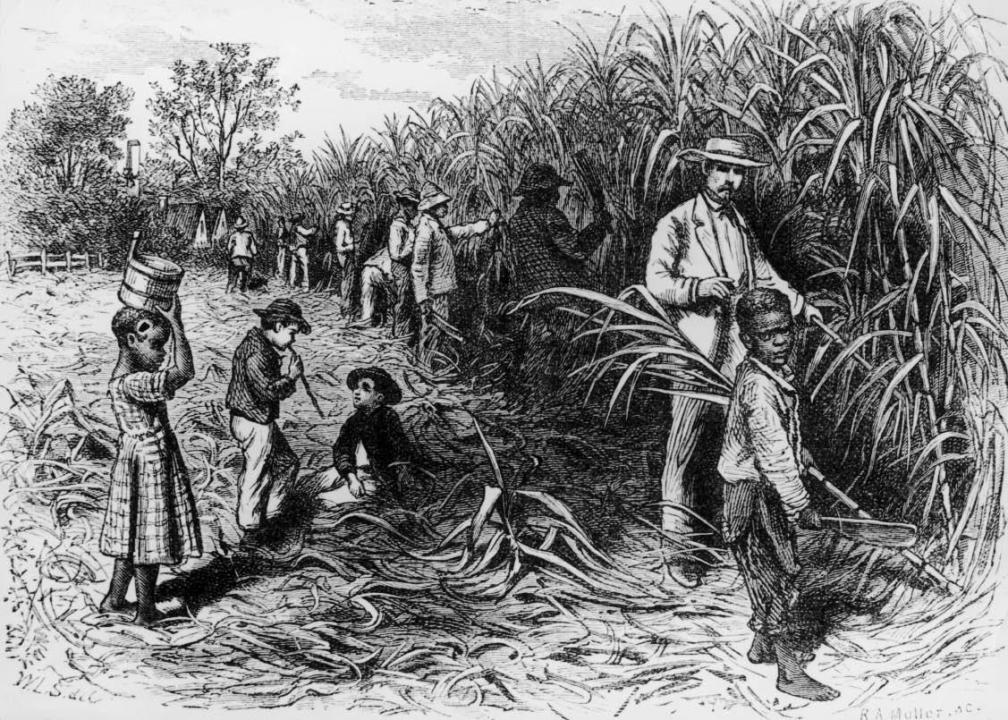

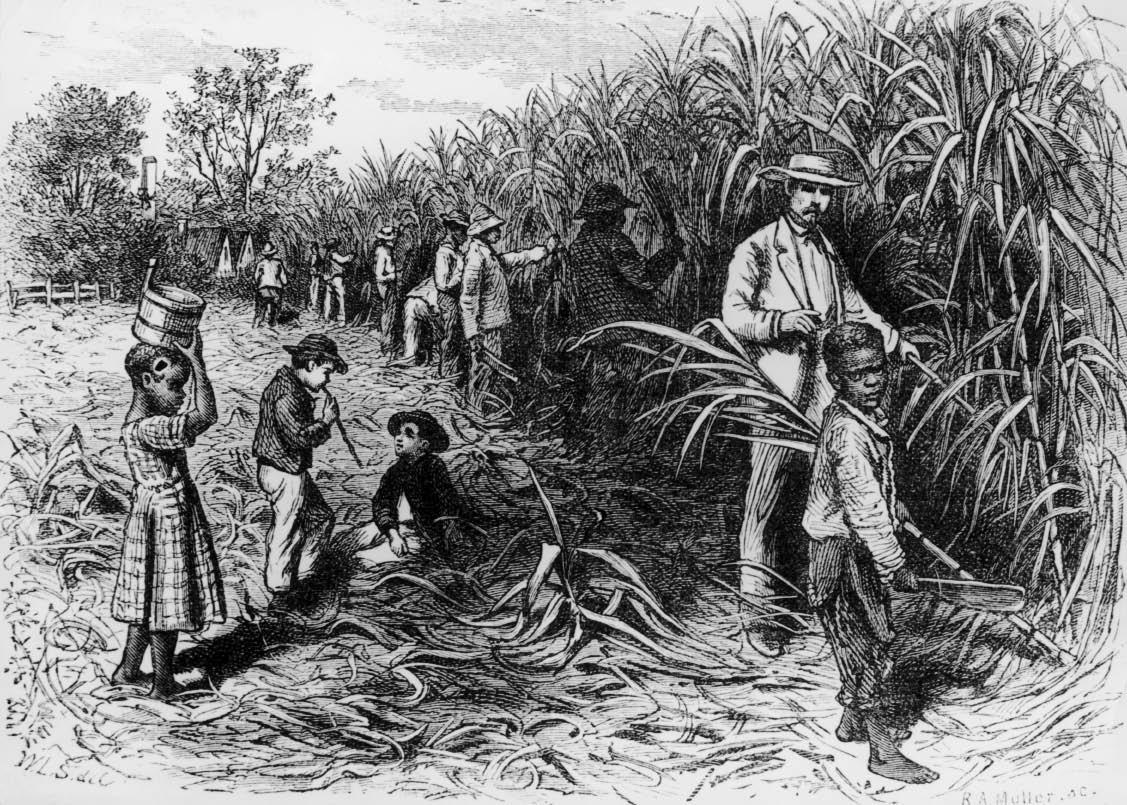

Rum is a young drink and, uniquely, it is possible to trace its origins precisely: to 1493, when Columbus took sugar cane cuttings to Hispaniola (what is now Haiti and the Dominican Republic). The first rum was made early in the following century and a couple later it became a link in the infamous ‘triangle trade’, taking slaves from West Africa to the New World, swapping them for spices, tobacco and molasses for Europe and then going back to Africa with a bunch of stuff to barter for more slaves.

Like all spirits, rum is colourless and fairly neutral at first but from then on it establishes itself as the most diverse of all. Some young ‘white’ rum is left that way and is best avoided unless used for mixing and cocktails. Some is aged for between one and three years — generally in oak for dark rum and in steel tanks for white — and some is then coloured with caramel to make golden (‘oro’ or ‘ambré’) rum. The best gets the full oak-ageing monty and becomes premium (‘añejo’ or ‘rhum vieux’) dark rum. The finest of them are the result of endless blending processes, and the skill of the master blenders is no less than that of their Scottish and French counterparts. Thankfully, the cost of their labours — to the drinker — is considerably less onerous.

A whistle-stop tour of the Caribbean reveals that the former Spanish islands of Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic (Brugal is particularly worth seeking out), along with Nicaragua, Venezuela and Guatemala, have traditionally produced a higher percentage of white (‘silver’ or ‘light’) rum. The rum map is changing fast but the former English territories — Antigua, Barbados, Bermuda (Gosling’s ‘Black Seal’ is special), the Virgin Islands (Pusser’s ‘Nelson’s Blood’ is divine), Guyana, Jamaica (Appleton Estate’s 21-year-old is mesmerising) and Trinidad & Tobago — have a predilection for the dark (‘black’) versions which have such strong ties with the Royal Navy.

The former French islands of Gaudeloupe, Haiti (Barbancourt’s 15-year-old is often cited as the finest rum of all but — for obvious reasons — it’s increasingly hard to find) and Martinique specialise in ‘rhum agricole’, which is distilled only from fermented fresh sugar cane juice and prized over the cheaper molasses-based ‘rhum industrielle’ versions that the French turn their noses up at (and continue to make). The aged white rums made in that style (which is effectively the same as Brazil’s samba-enhancing cachaça) can be wonderfully complex things to contemplate, full of coconut essences lifted by citrus zest.

My new favourite rum is Zacapa, and — prove me wrong — I think it’s unique in bringing everything together, combining the freshness of the agricole method with the serious oak treatment, specifically in barrels used for ageing unctuous Pedro Ximenez sherries. It’s from Guatemala, where not only are there serious mountains to climb in order to make some hooch — mostly in postcard-perfect volcano form — but plenty of good reasons for needing some.

Peter takes his rum neat — sodomy and the lash merely confuse the issue

Comments