George Orwell took a dim view of competitive sport; he found the idea that ‘running, jumping and kicking a ball are tests of national virtue’ absurd. ‘Serious sport has nothing to do with fair play,’ he wrote in Tribune after scuffles broke out during the Russian Dynamo football team’s 1945 tour. ‘It is bound up with hatred, jealousy, boastfulness, disregard of all rules and sadistic pleasure in witnessing violence: in other words it is war without the shooting.’

Suzanne Lenglen’s loose-fitting knee-length tennis dresses inspired the new ‘style sportif’ of Coco Chanel

Baron Pierre de Coubertin, visionary founder of the modern Olympics, took the opposite view: to him the three words ‘Faster, Higher, Stronger’ represented ‘a programme of moral beauty’. The 1924 Paris Olympics, the first truly international games and the last over which he presided as IOC president, were his final chance to realise that programme.

Though it lacked the razzmatazz of this year’s edition, Paris 1924 was more ambitious in scope. It featured an international arts competition with a roster of famous judges – the painting prize jury included Sargent, while Ravel and Stravinsky sat on the music panel. But as the Fitzwilliam’s exhibition reveals, the sporting contests had more impact on morality and aesthetics, not always in the ways de Coubertin intended.

Paris 1924 marked many firsts, not all of them athletic. African-American long-jumper William DeHart Hubbard took home the first gold won by a black athlete in an individual event and black midfielder José Andrade became the breakout star of the victorious Uruguayan football team. But the real game-changers in Paris were the women. Lucy Morton, a working-class lass from Blackpool, astonished the judges by winning gold in the 200m breaststroke – the British swimming team’s only medal – despite having lost five teeth in a Paris taxi crash. The big sensations, though, were the tennis players.

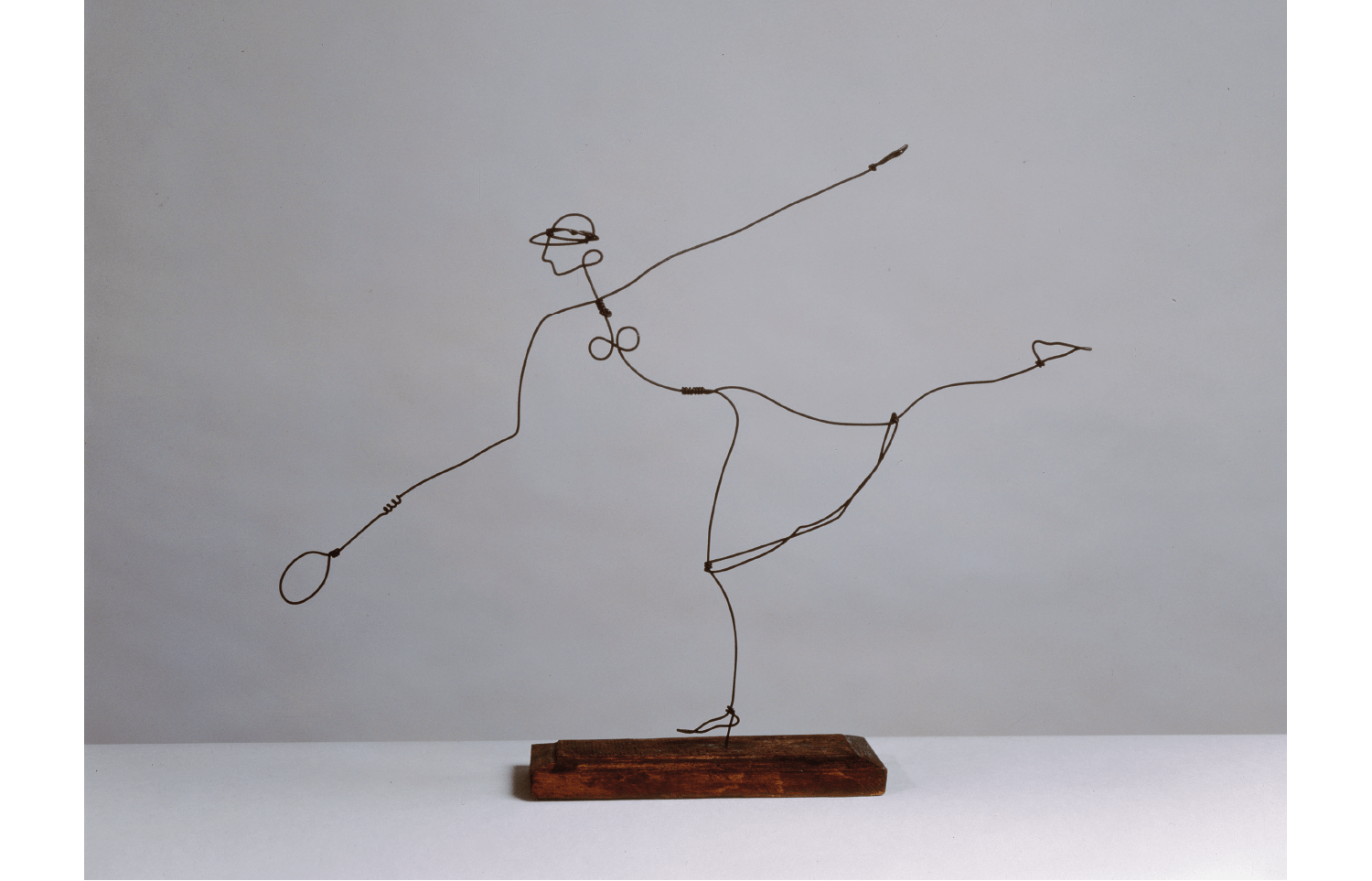

The American Helen Wills and the French Suzanne Lenglen became overnight celebrities, fêted as much for their style as their athleticism. Wills’s signature white visor, featured by Alexander Calder in his weightlessly balletic wire sculpture ‘Helen Wills I’ (1927), became the must-have accessory for women on the French Riviera, while Lenglen’s loose-fitting knee-length tennis dresses inspired the new ‘style sportif’ of Coco Chanel. Playing up to her flapper image, Lenglen sipped cocktails during changeovers and thrilled spectators with her revealing high kicks: an illustration by René Vincent for La Vie Parisienne shows her mixed doubles partner blushing at the sight of her bloomers.

At Paris 1924, the sports celebrity was born. Wills would appear in action on a cigarette box, but it was American swimming champion Johnny Weissmuller, winner of three golds and a bronze, who really cashed in. ‘Is this the World’s Perfect Male?’ asked Movie Mirror after the swimming hunk was signed to play Tarzan in 1932. Photographed slicked in baby oil as the ‘Discobolus’ in publicity for that year’s Los Angeles Olympics, Weissmuller couldn’t know that Hitler would adopt the sculpture as the emblem of the 1936 Berlin Olympics and the embodiment of Aryan manhood.

For artists, the classical ideal was hard to shake: doodling over a photo in Excelsior, Picasso turned 1923 Tour de France champion Henri Pélissier into a laurel-crowned athlete and Mme P into a winged Victory. Modernists tried to break the mould, with mixed results. Futurist Enzo Benedetto’s ‘Cyclist’ (1926) is a dynamic coil of wheels within wheels and George Grosz’s ‘The Cycle Race’ (1913) whizzes past in a blur, but his static ‘Gymnast’ (c.1922) is a human dumbbell. Robert Delaunay’s ‘Runners’ (1924) lollop along like middle-aged joggers, their spherical heads bobbing in unison with the Olympic rings. I wasn’t sure what Gino Severini’s ‘Dancer No. 5’ (1915-16) was doing in the show – the cancan has yet to be recognised as an Olympic sport – but he did go on to design the mosaics in the Foro Italico sports complex built by Mussolini in a failed bid to host the 1940 Olympics.

Before the Berlin Olympics, athletes were naive about the use of sport for political purposes. Wills turned down an invitation to partner Lenglen on a tour of North America in 1926 only to accept an offer from Mussolini for a tour of Italy. She was lucky to have a fallback career as an artist – her 1928 coaching manual Tennis was illustrated with her own drawings – but the options for past champions were limited. After her victorious homecoming, Lucy Morton performed at Blackpool Tower Circus alongside bareback riders and a female lion tamer. The cross-dressing French discus-thrower and shot-putter Violette Morris, barred from the 1928 Olympic team for wearing trousers in public without a police permit, became a music-hall chanteuse.

There’s little future in being faster, higher, stronger. Who would have imagined the great Usain Bolt advertising a fast-acting washing liquid on British telly? When it comes to competitive sport, I’m on Orwell’s team. He would have applauded Ireland’s record in the 1924 Olympics, taking home just two medals in the arts competitions: a silver for Jack Yeats’s painting of ‘The Liffey Swim’ (1923) and a bronze for Oliver St John Gogarty’s ‘Ode to the Tailteann Games’. Chapeau!

Comments