On the back of the British £20 note, J.M.W. Turner appears against the backdrop of his most iconic image. Voted the country’s favourite painting in 2005, ‘The Fighting Temeraire’ (1838) was Turner’s favourite too. It remained in his possession until his death; the 70-year-old artist swore in a letter of 1845 that ‘no consideration of money or favour can induce me to lend my Darling again’. But I suspect he would have approved of his darling’s current loan, along with that letter, to the Laing Art Gallery in Newcastle as part of the National Gallery’s bicentenary programme of loans of national treasures to regional museums.

Turner relished the atmospheric effects of industrial pollution

While other beneficiaries of the programme have been content simply to put their loans on display, the Laing has pushed the boat out with a show of 60 works – including 20 more by Turner – on the theme of ‘Art, Industry & Nostalgia’. For the Newcastle gallery the occasion represents a homecoming, because the Samson and the London – the two tugs hired to tow the hero of Trafalgar from Sheerness to Rotherhithe in 1838 to be broken up for its timber – were built on the Tyne. And the coal that powered them probably came from there too.

When Turner painted his bittersweet elegy to the age of sail with its squat black paddlewheel steam tug, funereal as Charon’s ferry, puffing pollution over the ghostly warship in its wake, coal from Newcastle powered the capital and fuelled the industrial revolution closer to home. Charles Turner’s moonlit mezzotint ‘Shields, on the Tyne’ (1823), after Turner’s watercolour, shows keelmen loading coal onto a collier while smoke rises from a smelter behind them. For the purposes of atmosphere, a man-made cloud of smoke and steam was as good as a storm cloud to Turner.

According to Ruskin, one-time owner of the blustery seascape ‘Yarmouth, Norfolk’ (1820-30) with its telltale scribble of vapour on the horizon, the artist loved steamers. A trail of steam is a useful figure in a seascape because it tells you about the wind – or in the case of ‘Steamer and Lightship’ (c.1838-9), with its ribbon of turpsy grey paint unfurling lazily against a blue sky, the lack of it. Wind or no wind, Turner relished the atmospheric effects of industrial pollution; with its factory chimneys belching smoke into the sky at sunset above what looks like a river of fire, his ‘Thames above Waterloo Bridge’ (c.1830-5) is an asthmatic’s inferno.

Among a local audience, there may be less nostalgia for the glory days of sail than for the heyday of shipbuilding on the Tyne, memorialised in Chris Killip’s powerful photographs of the last great supertankers to be built at Wallsend. Even he ‘didn’t know it was going to end as quickly as it did’: in ‘Looking East from Camp Road, Wallsend, 1975’ the hulk of the Tyne Pride under construction towers over an end of terrace house on Gerald Street; by ‘Demolished Housing, Wallsend, 1977’ the ship has sailed and all that’s left of Gerald Street is the street sign.

For a nation so proud of its industrial heritage, we’re rather careless of it. In the 1970s the great Chappel Viaduct bestriding Essex’s Colne Valley was nearly demolished when the government planned to close the ‘Gainsborough line’ running from Marks Tey to Sudbury; it took the Yom Kippur War’s threat to the nation’s supply of petrol to save the masterpiece of Peter Bruff, ‘the Brunel of the Eastern counties’, from destruction.

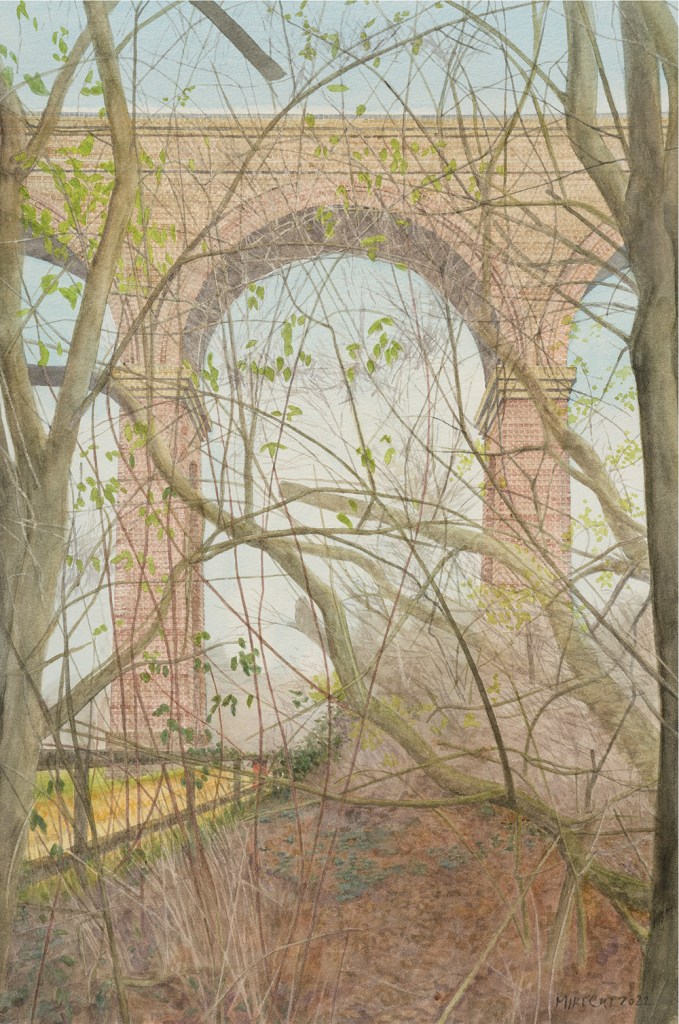

The year after its opening in 1849, local artist Edward Robert Smythe immortalised this magnificent monument to Victorian engineering in the style of Claude, complete with peasants imported from the Roman Campania; now, on its 175th anniversary, local artist Wladyslaw Mirecki has paid it an exhaustive tribute in a series of 64 watercolours framing its 32 arches from both sides. Since his move to Chappel in 1986, the viaduct, visible from his home, has become Mirecki’s Mount Fuji. He has painted its arches in many lights and seasons, but for the complete works he chose the end of winter when it wouldn’t be obliterated in foliage. Armed with a pair of secateurs, he followed its course through woods, over railway scrubland, along streams – ‘I had to finagle a bit to fit in the water’ – through neighbours’ gardens and across a Millennium orchard planted by local schoolchildren, past wartime pillboxes and tank traps, football fields and children’s playgrounds, omitting no detail: the dog waste bins add accents of red like the buoys in Turner seascapes.

Currently displayed in the goods shed of the charming East Anglian Railway Museum at Chappel & Wakes Colne Station, Mirecki’s magnum opus is a 64-gun salute to a piece of Victorian infrastructure constructed in the style of a Roman aqueduct from seven million bricks just to carry a branch line. That is a cause for nostalgia in itself.

Comments