Ditchling in East Sussex is a small, picturesque village with all the trappings: medieval church, half-timbered house, tea shops, a common, intrusive new housing developments down the road, a good walk from the nearest train station and the Downs on its doorstep. But the resonance of the place owes much to the remarkable artistic activity that has bloomed since Eric Gill moved his family there in 1907. It was part craft commune, part lay monastery, a living experiment in distributism, the radical Christian political philosophy that held that land should be distributed as widely as possible. It was an attempt to resurrect the medieval guild. Gill’s Catholic community even had its own: that of St Joseph and St Dominic, which held that ‘all work is ordained to God and should be Divine worship’ and ‘making the goodness of the thing to be made the immediate concern in work’. Dominican friars were frequent visitors.

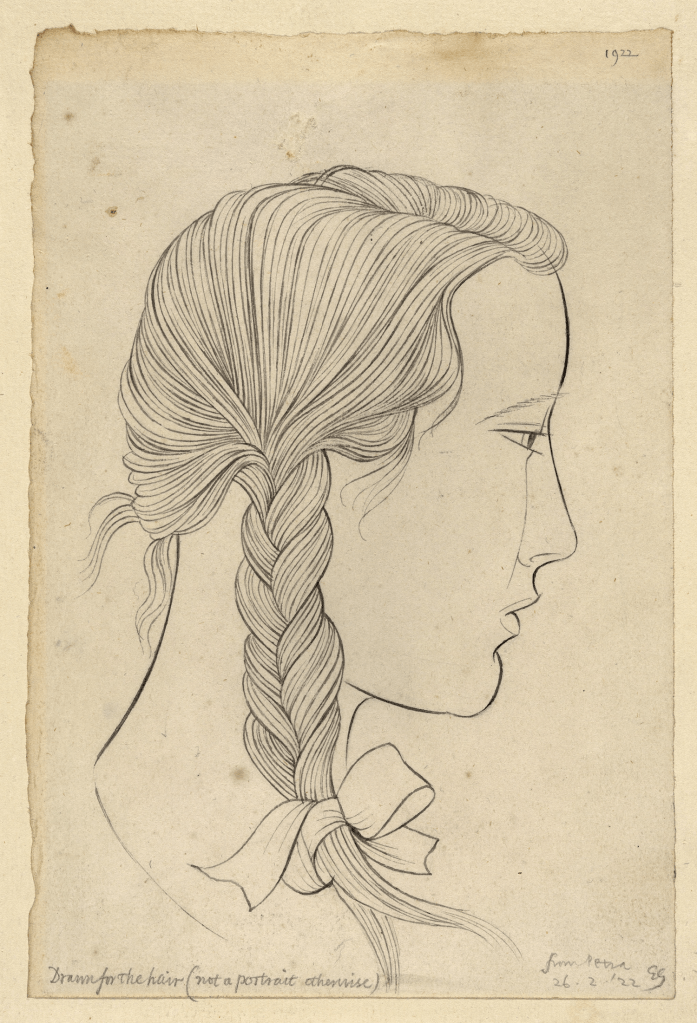

In the early 1920s, Gill’s distributist experiment was something of a tourist attraction, with a succession of visitors dropping by to observe this community of craftsmen (Gill repudiated the effete term ‘artist’), with its woodworking, stonecutting, silverwork and printing. (Hilary Pepler ran St Dominic’s Press, and Edward Johnston – the one member of the group who declined to convert to Catholicism – was their lettering man.) David Jones, painter and poet, was introduced to Ditchling by Mgr John O’Connor – G.K. Chesterton’s original Father Brown – and was, for a time, engaged to Gill’s daughter Petra. The women did the domestic chores and some skilled work such as weaving.

Jones would much later say that ‘if I were to write down a typical day at Ditchling in 1922, it would be very hard indeed to convey the naturalness, unaffectedness, happiness, sincerity, rightness, freshness which we at the time felt and that in spite of the usual tensions, strains, squabbles, etc. But just to give an account of it now would seem affected, arty-crafty, self-consciously “religious”, eccentric, mistaken if not actually bogus.’ In the same letter he reflects on the ‘extreme difficulty of conveying to chaps now the particular freshness or springtime… of the… Weltanschauung of the 1920s’.

It’s David Jones who steals the show without dominating it

The workshops and chapel of the group were – unforgivably – demolished in 1989, and the houses sold privately (one owner painted over a mural by Jones) but the establishment of the Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft was some compensation for the loss. It was reinvigorated in 2013 and, notwithstanding its small size, has held excellent exhibitions of local artists and associates of the Ditchling group, including Edward Johnston and Frank Brangwyn. Now, 40 years on, it presents another reworking to expand the range of artists on show and deal with the problem of Eric Gill – now best known for interfering with his daughters, plus his dog.

On the first, there is a striking assembly of portraits on show of individuals associated with Ditchling, extending beyond the Guild, from Mary Gill, Eric’s wife, eyes bent on her work, to Amy Sawyer, a flamboyant artist who wrote plays for local performance. There’s fine textile work, notably Grace Denman’s striking silkscreen prints, and a reimagining of Ethel Mairet’s weaving workshop, complete (for the multisensory route is the way to go nowadays) with an olfactory station for smelling her dye plants, including cabbagey woad. Ditchling’s tradition lives on: the illustrations here by John Vernon Lord for Aesop’s Fables are exquisite and playful.

But it’s the work of the Guild that remains outstanding and that ethos of ‘the goodness of the thing to be made’ is evident in every medium, from Dunstan Pruden’s exquisite silver work to Joseph Cribb’s curvy, sensual carvings in wood and stone to Johnstone’s calligraphy. The radical character of distributism is there in Philip Hagreen’s funny anti-capitalist wood engravings. In one, the snake in Eden, ‘The First Advertiser’, is seen coiled around a tree. ‘Eat More Fruit,’ it demands. But it’s David Jones who steals the show without dominating it: his moving ‘Our Lady of the Hills’ (1921) is the poster image and I loved the engaging, perky ‘Agnus Dei’ he created for the guild chapel.

Gill, we know, experimented sexually with his two older daughters (the incest with his sister was consensual). There’s a curious little room, established on the advice of the Methodist Survivors’ Advisory Group, to which entrance by under-16s is discouraged, which aims to represent the achievements and personality of the girls in their own right, including Petra’s hand-woven wedding dress (see above). But separating these things from the rest means that lovely pieces – such as Gill’s studies of his daughters in admirable clear line and David Jones’s affectionate depiction of Petra – are presented as part of a problem. I’d have put the lot out on general display with a panel offering information about his sins.

Unless you’re a local, it’s a hike to get to Ditchling. But it’s worth it.

Comments