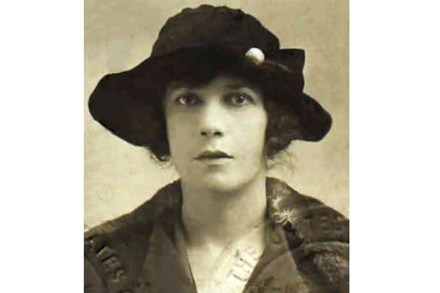

Driven to distraction — the unhappy life of Vivien Eliot

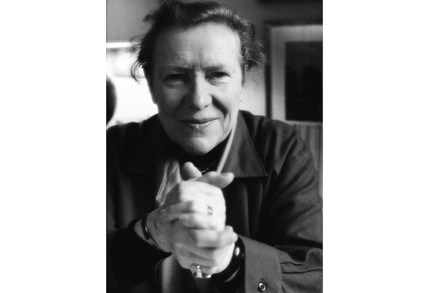

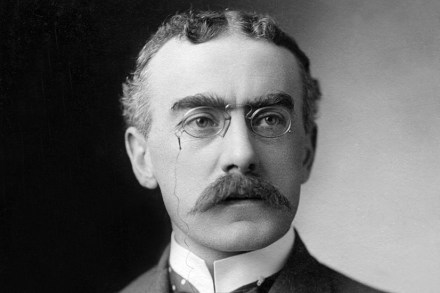

Do you think your mother slept with T.S. Eliot? That was the question I needed to ask the 98-year-old in front of me. It wasn’t easy. I’d never met him before. After some preliminary chat, though, I realised this affable man knew exactly where our conversation was heading and had pondered the question a good deal himself. The barrister Jeremy Hutchinson — Baron Hutchinson of Lullington — was the son of Mary Hutchinson, Eliot’s close friend. Infatuated with the poet for a time, she had met ‘Tom’ and his wife Vivien before Vivien’s adultery with Bertrand Russell, and some years before the publication of The Waste Land in 1922. When