Why were the Scots so much better at painting than the English?

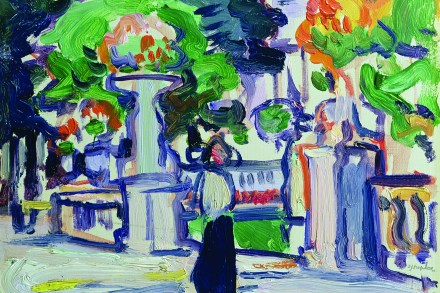

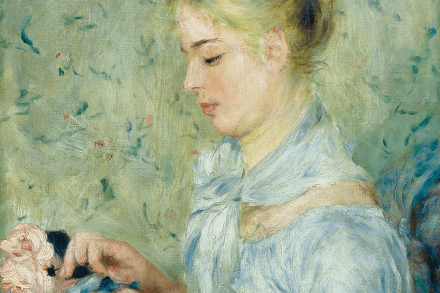

This exhibition is awash with luscious brushstrokes, but then that’s to be expected: it’s full of Scottish painting. Before the barren era of conceptual art, which most hope is over, people often observed that the Scots could paint while the English could draw. Why is a bit of mystery, but it was true right through the 18th and 19th centuries and well into the 20th. The Dovecot Studios exhibition opens with John Duncan Fergusson’s portrait of his lover and first muse, Jean Maconochie, painted about 1902. It’s a fabulous eyeful of brush marks. Her pale pink, oval face nestles under her black billowing locks, flanked by two glowing pearls dropping