The story goes that one day early in the 16th century Leonardo da Vinci was strolling through Florence with a friend. Near the Ponte Santa Trinita they came across a group of gentlemen disputing a point in Dante’s Divine Comedy. Seeing Leonardo, they asked him to explain the passage. At that same moment, Michelangelo Buonarroti also happened to hurry by, and Leonardo beckoned the sculptor over to interpret it for them. But Michelangelo, feeling he was being mocked, rounded on Leonardo: ‘Explain it yourself, you who tried to cast a horse in bronze, and couldn’t do it, and had to abandon the project in shame!’ With that he turned on his heels and stalked off, leaving Leonardo standing in the street embarrassed and furious.

Leonardo advised ‘David’ should be displayed with ‘decent ornaments’ (gilded leaves over his private parts)

The conflict between these two geniuses was real. Giorgio Vasari wrote that there was ‘the greatest disdain’ between them. They differed in every way: temperamentally, intellectually; in the media they favoured and the clothes they wore. But this tension was productive; out of it developed new ways of making art.

There was a third great artist present in Florence around that time, and from their examples he developed his own hugely influential style. Altogether the Royal Academy has extraordinarily rich material for the forthcoming exhibition, Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raphael: Florence, c.1504. That year was the epicentre of what came to be called the High Renaissance, and the eye of the creative storm was Florence.

Several of the most celebrated works ever created date from around that time. In October 1503, a Florentine civil servant named Agostino Vespucci made a note in the margin of a book by Cicero. In this he mentioned two paintings on which Leonardo was at work: the head of Lisa del Giocondo (that is the ‘Mona Lisa’), and another containing the head of ‘Anne, the mother of the Virgin’ (presumably this was ‘The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne’ that now hangs in the Louvre).

Meanwhile, Michelangelo was applying the finishing touches to a gigantic marble carving of David. On 14 May 1504, this naked colossus emerged from the courtyard of the Opera del Duomo where it had been made and was slowly trundled, upright in a cart, through the streets to the Piazza della Signoria (a journey which took four days). It may have been a few weeks before the ‘David’ made its triumphal appearance that Leonardo and Michelangelo had that public spat. Charles Nicholl, one of Leonardo’s most acute biographers, pointed out that this anecdote from an anonymous 16th-century manuscript seems to be an eyewitness account. He argued that the most likely time for the clash was the spring of 1504.

There was certainly reason for bad blood between the two artists just then. Late the previous January an extraordinary meeting had taken place. Its purpose was to decide where the ‘David’ should be located (apparently it was felt the sculpture was too splendid to go in the position originally intended, high on the roof-line of the Duomo).

Around the committee table sat Botticelli, Perugino, Filippino Lippi, Piero di Cosimo and Leonardo da Vinci, among others. Various suggestions were made about where to put this masterpiece, but only Leonardo was subtly – but distinctly – negative. He proposed that the ‘David’ should be tucked away in a relatively obscure spot. He also quietly drew attention to the most controversial aspect of the carving: its full-frontal nudity. Leonardo advised it should be displayed with ‘decent ornaments’ (it may be thanks to him that for centuries the ‘David’ wore a garland of gilded leaves over his private parts).

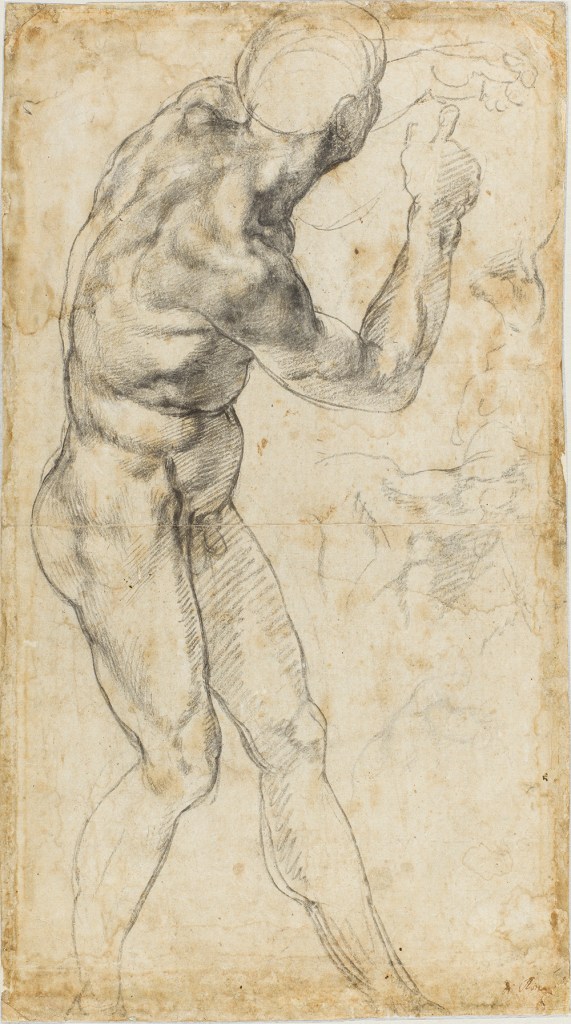

Evidently, Leonardo felt that he could have done a better job himself. He sketched a revised version with a more harmonious body, smaller head, and less unsettlingly heroic energy. Also, he made some notes which seem directed at Michelangelo personally. ‘You should not make all the muscles of the body be too conspicuous,’ Leonardo cautioned. ‘If you do otherwise you will produce a sack of walnuts rather than a human figure.’ (See below.)

Michelangelo, for his part, despised the aspects of art in which Leonardo excelled. What they call ‘landscapes’, he sniffed to a Portuguese friend many years later, were a trivial matter of depicting ‘the green grass of the fields, the shadows of trees, and rivers and bridges’. ‘Although it may appear good to some eyes,’ he concluded, ‘[landscape] is in truth done without reasonableness or art, without symmetry or proportion, without care in selecting or rejecting’. He doesn’t seem to have had a high opinion of naturalistic portraiture either. So much, then, for the ‘Mona Lisa’.

Someone in the Florentine government – it might have been Niccolo Machiavelli, then a senior civil servant – noticed this rivalry between the two leading artists in the city and decided to exploit it. Vespucci (who worked for Machiavelli) noted – again in October 1503 – that Leonardo had just agreed to paint a huge mural in the council chamber of the Republic. This was to depict the Battle of Anghiari. Almost a year later, in late summer of 1504, a second enormous picture for the same room was commissioned from Michelangelo: ‘The Battle of Cascina.’

If they had been completed, these works would have presented the most extraordinary exercise of compare and contrast in the history of art. But, for differing reasons, they weren’t. Leonardo lost interest and drifted away, apparently because – typically – he had made use of an innovative technique that didn’t work. It was just this trait that Michelangelo was targeting in the exchange quoted above. In Milan, Leonardo had made a clay model of an enormous horse 26ft high but, as we know, Michelangelo didn’t think it could ever have been successfully cast in bronze. ‘Did those blockheads in Milan believe what you promised them?’ he is supposed to have asked.

Michelangelo, however, had his own problems of non-delivery. ‘The Battle of Cascina’ was never completed because Michelangelo was summoned to Rome to work on the tomb of Pope Julius II. Because of its scale and ambition, he didn’t manage to finish this project for four decades – and then only after much anguish and in greatly reduced form.

Meanwhile, from late 1504 or early 1505 a third great artist was watching and learning from the other two. Raffaello Sanzio, born in 1483, was eight years younger than Michelangelo and more than 30 years Leonardo’s junior. As far as the Florentines were concerned, he was also a foreigner from distant Urbino.

‘Did those blockheads believe what you promised them?’ Michelangelo is supposed to have asked Leonardo

Among various cutting-edge works, Raphael studied the ‘David’ and the ‘Mona Lisa’, plus the holy families and Madonnas of Leonardo, and others by Michelangelo such as the Royal Academy’s own ‘Taddei Tondo’ (itself both an imitation of and a response to Leonardo).

Characteristically, Michelangelo became paranoid about this youthful rival. In January 1506, he wrote from Rome to his father in Florence asking for a certain chest, probably full of drawings, to be kept away from the public. He also asked for ‘that marble of Our Lady’ (probably the Bruges Madonna) to be ‘moved into the house, likewise’. His father was ‘not to let anyone see it’. Perhaps he had Raphael particularly in mind.

Many years later, in a bitter moment, Michelangelo wrote that Raphael, with his ally the architect Bramante, had schemed against him, causing all his troubles with Pope Julius. ‘Raphael had good reason to be envious since what he knew of art he learnt from me,’ he explained. This was not entirely fair. Raphael also borrowed a great deal from Leonardo – as well as from his master Perugino.

That’s normal. Artists, as Anthony Caro once put it, are ‘eaters’. They take what they need from each other. Raphael digested the idioms of the two elder geniuses and produced his own personal synthesis. It was so successful that in the next decade he eclipsed Michelangelo. Pope Julius’s successor, Leo X, preferred to work with Raphael, complaining to Sebastiano del Piombo that Michelangelo was ‘terrible’, by which he meant what we would call impossible – ‘one cannot deal with him’.

Raphael’s harmony, ease and fluency made him the idol of European art lovers for centuries. In the modern age, many are more excited by Michelangelo’s majestic intensity and Leonardo’s mixture of omnivorous curiosity and enigmatic strangeness. Whichever you prefer – or whether you feel no need to choose – one thing is clear. The rivalry and mutual emulation of this trio of mighty talents make Florence around 1504 seem oddly contemporary. The artist type, it seems, hasn’t changed much in 500 years.

Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raphael: Florence, c.1504 is at the Royal Academy until 16 February 2025.

Comments