So, the Turner Prize: where do we start? It’s Britain’s most prestigious art award, one that used to mean something and now attracts little more than indifference. Taking place every year, it grants £25,000 to a winner chosen from four shortlisted artists, all of whom are obliged to display work together either at Tate Britain, or at a regional gallery. The latest iteration, at Bradford’s Cartwright Hall, is the best in a while – but before we get to that, some context. The Turner was established in 1984, but only really grabbed anyone’s attention when Channel 4 began televising the prize-giving ceremony in the 1990s. That this coincided with a sensationalist BritArt boom helped, too: my own first encounter with the Turner came in 1995, when Damien Hirst won and Blue Peter aired a segment on his expensively embalmed menagerie. ‘Wow,’ I thought, ‘this is scary.’

The Turner Prize might now be at ease with the fact that nobody much cares

Since those days, the zeitgeist has dissipated and any ‘controversy’ the prize has generated has been of a distinctly manufactured flavour. In the current show, that lightning-rod element comes courtesy of Rene Matic (b.1997), a likeable trans artist doing their best to resist the pressures of ‘The System’. Yes, I know what you’re thinking: identity politics. But Matic’s room is nice enough, in its sub-Wolfgang Tillmans way. Photos of nightclub scenes and anti-establishment graffiti are set behind glass panes at a tilt. A big flag, bearing the inscription ‘NO PLACE FOR VIOLENCE’ – a reference to a statement issued by American politicians following the attempt on Donald Trump’s life last summer – divides the central space. I’m not sure there’s much more to it, but it’s all beautifully presented.

Across the way, Zadie Xa (b.1983) has fielded a highly Instagrammatic display of paintings and assemblages inspired by Korean mysticism. I’m not mad on ‘witchy’ art and I’d expected to hate this. The thrill was that by decking her gallery out with a reflective floor and suspended seashells that ‘talk’ to the visitor, Xa has created a proper spectacle. I dislike it for its flimsiness and whimsy, but I found myself having fun with it. The last two artists, I’m familiar with: Nnena Kalu (b.1966) is severely autistic, to the point she can’t really speak. I saw the show for which she was nominated, where her sculptures – mad, phallic things hewn from tape, fabric, plastic and whatever else – were suspended from the ceiling of a disused power station outside Barcelona. They looked interesting there, but they don’t in a wood-panelled solarium just beyond Bradford’s city limits. Her drawings – mad, expressionistic squiggles that nod to both Cy Twombly and vintage Ralph Steadman – are more lively, but it’s all a bit slight.

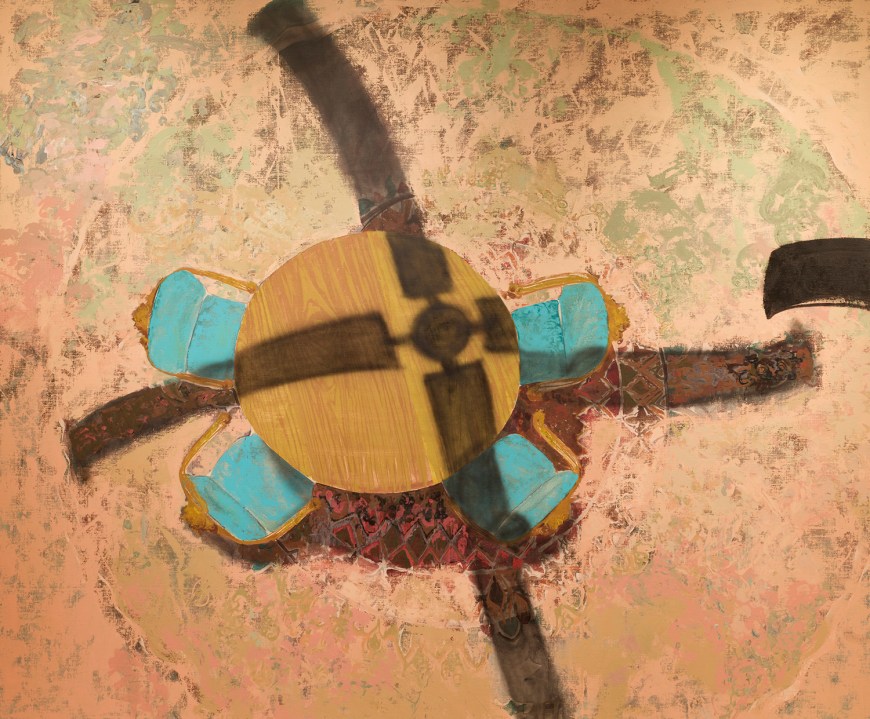

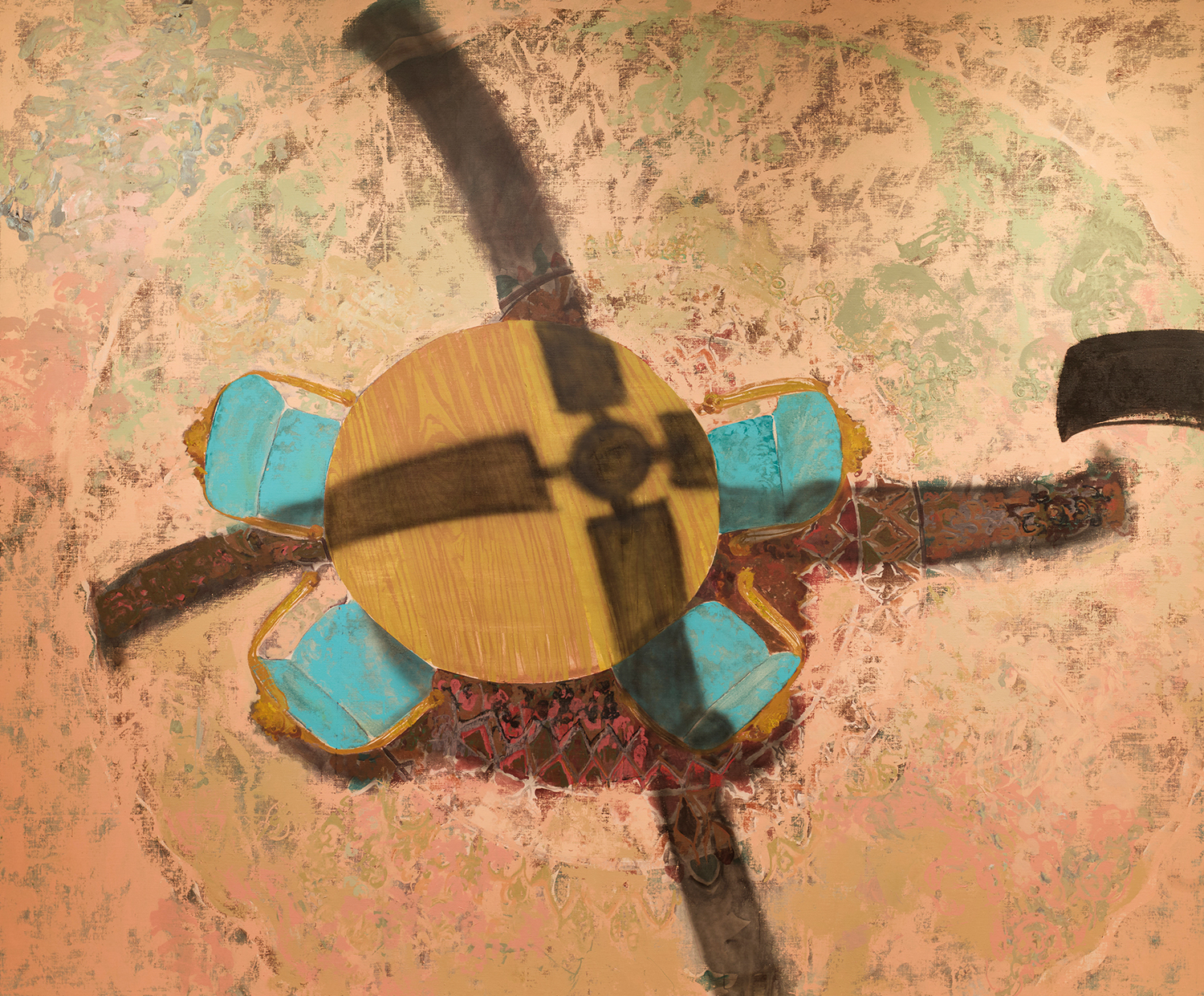

Moving on from displays that look like good art to one that actually contains it, we come to the painter Mohammed Sami (b.1984). Originally from Baghdad, Sami endured a miserable stint as one of Saddam Hussein’s pet portrait painters in his youth, and the horror of that time still clearly haunts him. His 2023 exhibition at Camden Art Centre was one of the most exciting contemporary painting shows I’ve seen, announcing the arrival of a supreme talent with the capacity to reinvent his form. Menace is ever present in these works, whether embodied by a lightbulb throbbing red as a metonym for dictatorship’s total control of message, or via the sinister green lasers quadrisecting a huge, ominously lit woodland scene in a huge landscape called ‘The Hunter’s Return’. He even includes a likeness – of sorts – of his late client Saddam, obscuring everything but the dictator’s chin, moustache and medal-bedecked chest with what looks like cheap domestic paint. If he doesn’t win, something has gone very wrong here.

If Mohammed Sami doesn’t win, something has gone very wrong here

Not a rapturous exhibition, then, but an agreeable one that largely swerves the more irritating fringes of British contemporary art. Nothing is explicitly embarrassing, even if some displays come close, and it seems to be going down well in Bradford. I came away with the impression that after years of striving for ‘relevance’, the Turner Prize might now be at ease with the fact that nobody much cares.

Comments